The writer Christine Coulson spent much of her 25-year tenure at the Metropolitan Museum of Art composing wall labels for the museum’s galleries. Beneath the standard “tombstone information” — artist name, date, medium — she had 75 words to describe and contextualize the artwork at hand. Each label was an exercise in distillation, precision, and, by necessity, omission.

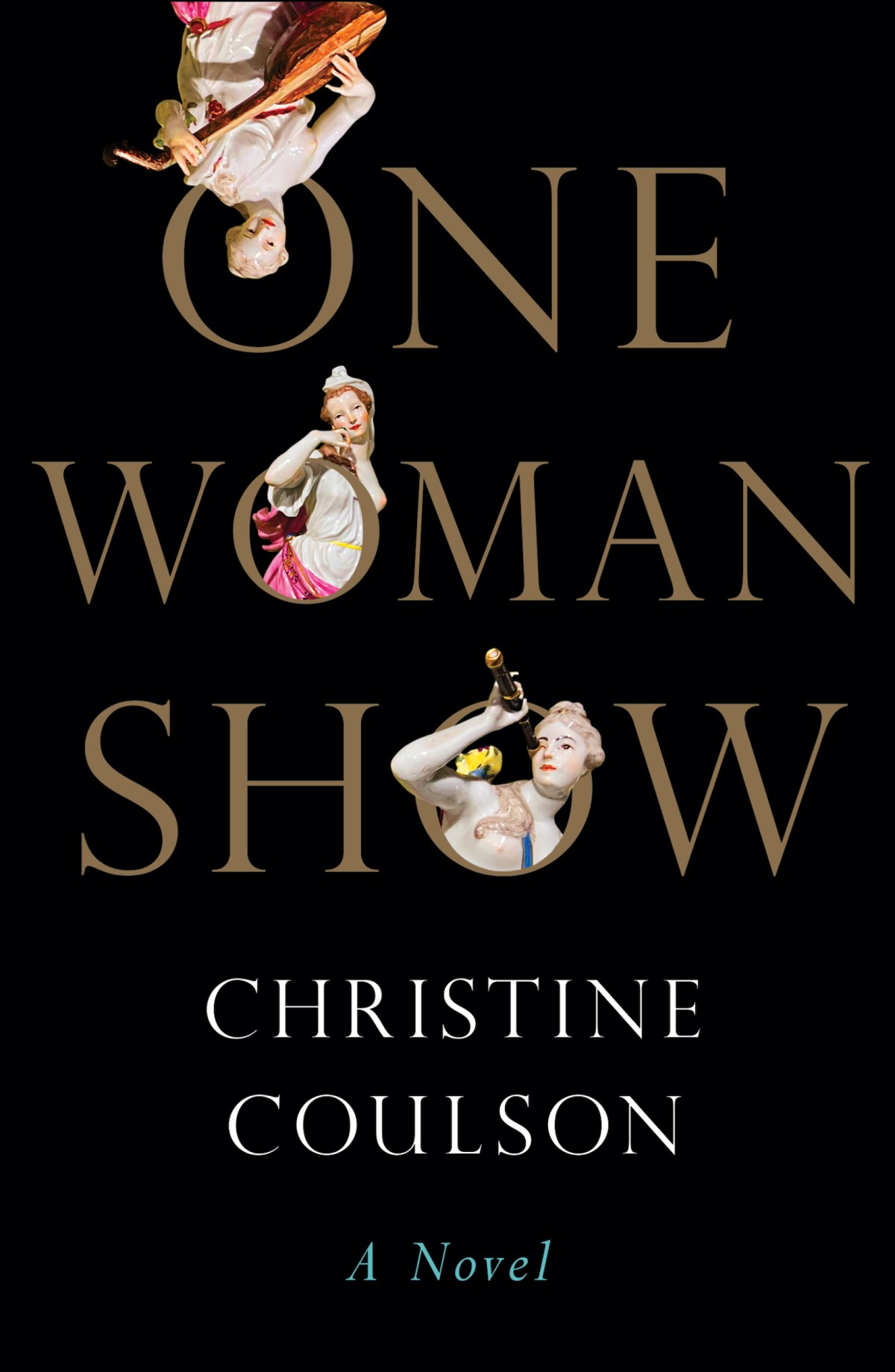

Coulson’s sophomore novel, One Woman Show, explores the formal constraints — and narrative possibilities — of the museum wall label. Chronicling the turbulent life of a fictional 20th-century socialite named Kitty Whitaker, the novel is narrated almost entirely through wall labels, a conceit that would be gimmicky were it not so deftly executed. Each label is a pointed vignette of Kitty’s life: her charmed childhood, rebellious adolescence, three ill-fated marriages, and tragic twilight years (some of them spent working at The Met). In truth, though, the plot doesn’t much matter: One Woman Show is, above all, a linguistic feat. Coulson’s pithiness, lexical precision, and nimble wordplay steal the show from the protagonist ostensibly at its center.

Born in 1906, the “golden child” of prominent New York City WASPs, Kitty understands herself to be an objet d’art, thus justifying Coulson’s literary experiment. Kitty recognizes early on “the limited real estate of any prized pedestal” and aspires to make herself “the most treasured object” — i.e., the most marriageable young woman — in the “garniture” of her upper-crust milieu. Upon meeting her future husband, heir to a mining fortune, at age 18, she is “electrified by the prospect of being installed as the centerpiece of this new dynastic collection.” (Previously, she had belonged to the “collection of Martha and Harrison Whitaker,” her parents; with each marriage, she is accessioned into a new collection.) Once married, Kitty is deemed “a masterwork of aesthetic and nuptial achievement.”

Such clever applications of art-world jargon abound. The concept of “provenance,” for instance, is used throughout as a class marker, invoked to describe the pedigrees of Kitty, her peers, and her spouses. (Her first husband is of “Pittsburg provenance”; her second, a Portuguese royal, of “regal provenance.”) Such language also euphemizes the more painful moments of her life. After a beating from her second husband leaves her with “significant abrasions to her varnish,” Kitty begins the “shrewd planning of a revived solo exhibition.” Everything, from her multiple miscarriages, disordered eating, kleptomania, and even death, is described obliquely, glossed over until it shines. What’s left out, kept out of frame, matters just as much as what’s on display.

The language we use to describe art — and how it simultaneously constructs and obscures reality — has long preoccupied Coulson, as evidenced by her debut novel, Metropolitan Stories (2019), a behind-the-scenes look at her former place of work. With One Woman Show, she zeroes in on wall labels (and the invisibilized labor behind them) to curate a gallery exhibition of one woman’s lifetime — less a collection of objects than the composite of a subject. Alas, that subject, Kitty Whitaker, is a rather two-dimensional character. But this, too, is part of Coulson’s project: to show not only the versatility of language, but also its limits; to remind us that a 75-word caption can complement and even enhance our experience of an artwork, but it can never capture it entirely.

One Woman Show by Christine Coulson (2023) is published by Avid Reader Press and is available online and in bookstores.