LONDON — Armies attack, parry, bludgeon, obliterate, all in relentless pursuit of their pitiless goals. As do artists. Artists do not pussyfoot either. Art too can be, and often is, a species of combat, a fight to the death.

Take Leon Kossoff and his practice, which we can divide, for the sake of argument, into drawing and painting. Kossoff painted and drew throughout his life. Springing to Life, a new, extensive exhibition of his drawings (the first since his death in 2019) brings these issues — of lifelong battle and confrontation — into sharp and fascinating focus. The floors and walls of his studio overlooking the street in the north London house where he lived were as horrifying for any unsuspecting art critic to behold as any war zone. And all the more surprising because the man himself, when met at the door with a degree of queasiness and suspicion, was so reticent, shy, and mild-mannered.

Why? Because he painted on board, which enabled him to engage in physical punishment, fight-back, to wrestle with a painting until it was battered into submission. This involved, always, the application of paint, often in thick globs or slatherings, followed by a furious scraping away. On and on it went. An application and a scraping away. The floors and walls looked like the worst of all possible crime scenes. Only the intense glare of lighting and walkie talkies were absent.

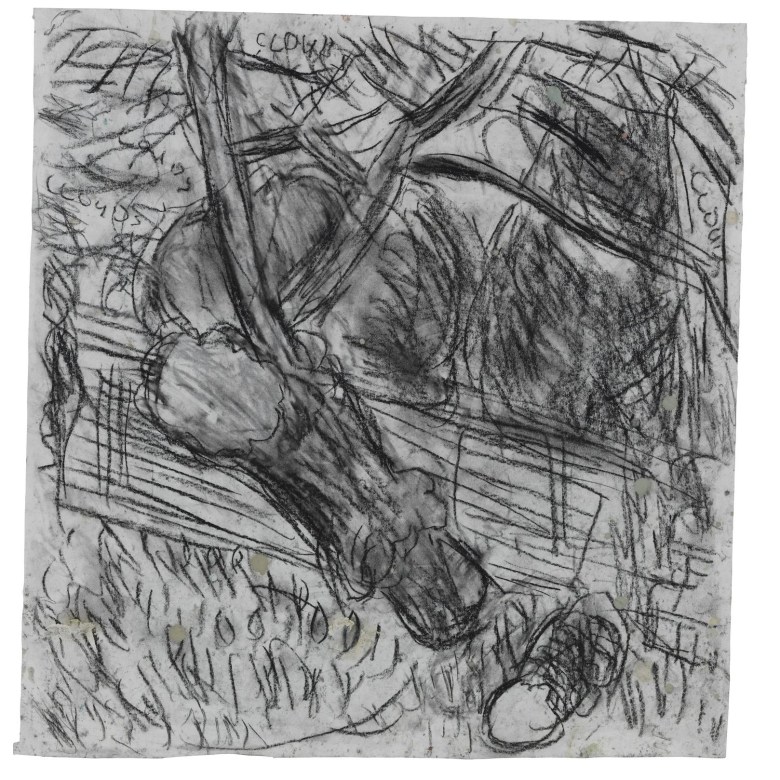

But the drawings were something quite different. They were just as important — just as obsessively important, you could say, because Kossoff was an obsessive man. Yes, he drew every day, every morning. “Why though?,” I once asked. Every day began with drawing because he always feared that he might have lost the ability to draw, and to draw again was to prove quite the opposite, much to his relief and satisfaction.

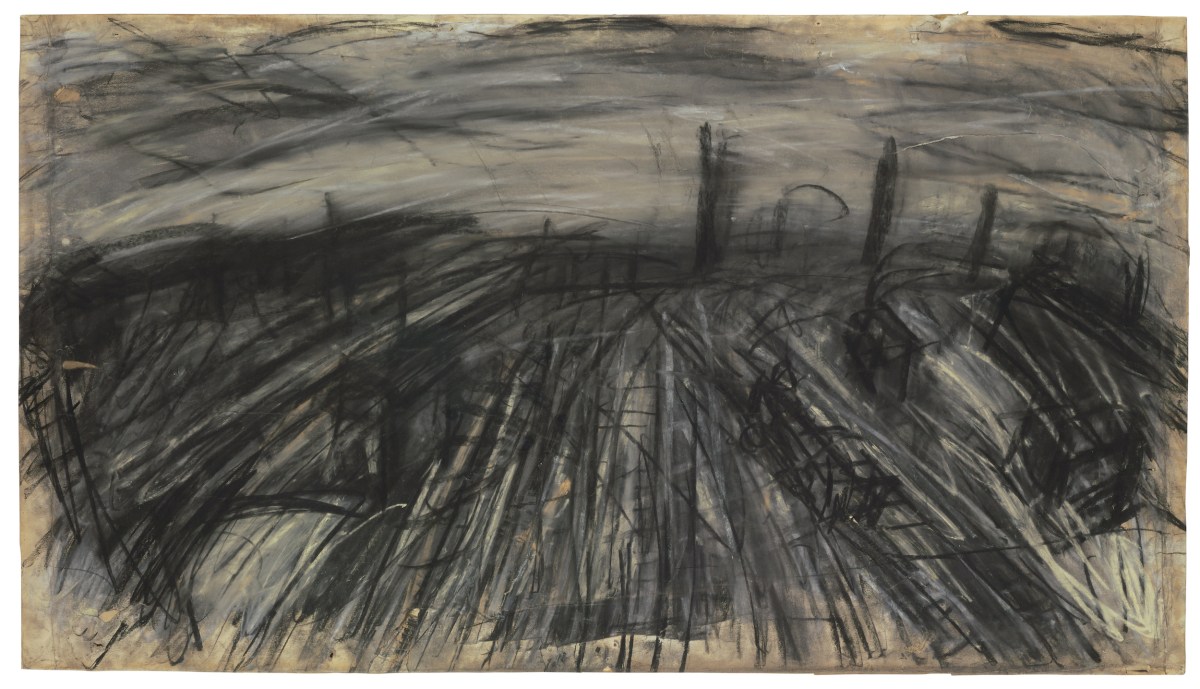

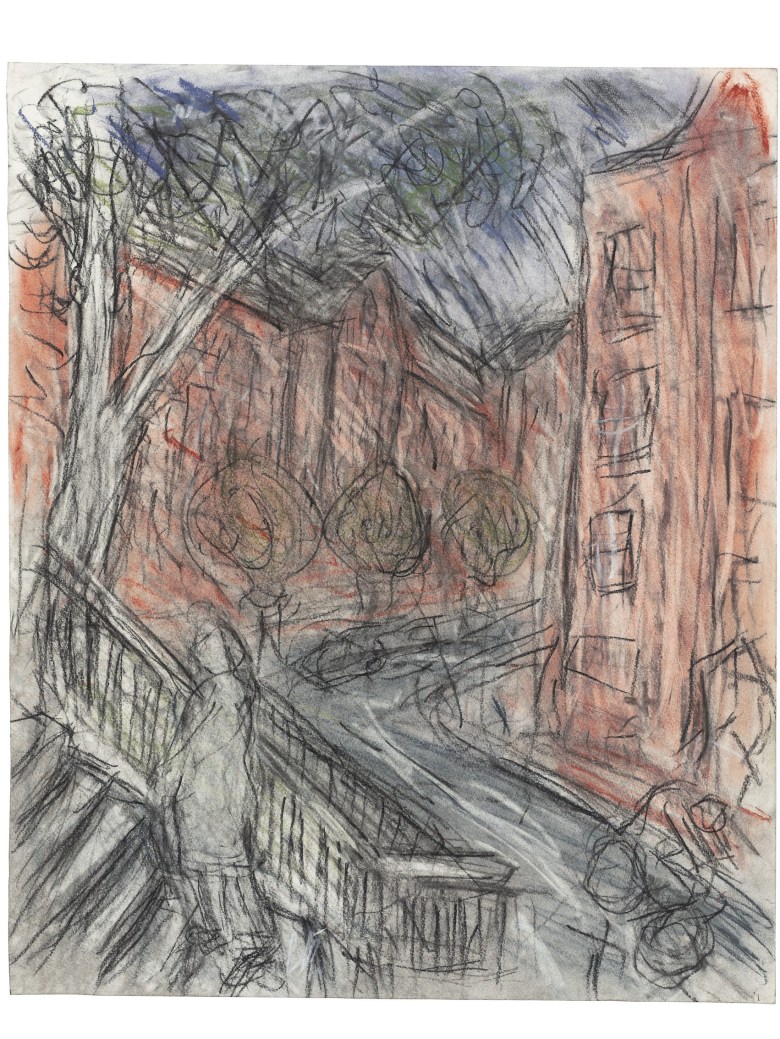

So the drawings were the very key to his continuing existence as an artist. There were four main subjects: his models (the same ones again and again, over years, which included his parents); the buildings of London; the railway network and all it had spawned by way of junctions, stations, the curving outreach of its tracks; and his take on the great painters of the past.

Kossoff’s models do not smile. They do not directly engage with us at all. Heads and bodies are usually slightly averted. Bodies hang slack and ponderous. “Father in an Armchair” (1957), in charcoal and gouache on paper, is asleep, but this father’s sleep looks like a final act of submission to world weariness. When railways rush into view — perhaps a train roaring across the bottom of the garden, or outside King’s Cross Station, where beings rendered in little more than light graphic notation move as fast and furious as the daily timetable must forever relentlessly dictate — Kossoff’s fingers take fire. And then there is Hawksmoor’s great church at Spitalfields, to which Kossoff, the enthralled Jewish onlooker, never fails to return. What is it about the list and the lean of this church? What was the conversation between the artist and the backward-rearing monumentality of its steeple? Was the church expressing surprise?

Springing to Life: Drawings by Leon Kossoff continues at Annely Juda (23 Dering Street, London, England) January 20. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.