The great painter William Blake (1757-1827) traveled far in the realms of gold, to borrow a phrase from John Keats, but much less far in the body. (He lived in various parts of London for all but a little more than three years of his relatively long life.)

So, where did he go when he was not actually using his legs? According to Blake himself, the only known authority, he regularly conversed with Sophocles, Aristotle, and Jesus. And then there were the angels, many of whom were also his fast friends. He had his first angelic conversations on Peckham Rye, a glorious park, still thoroughly angelic in appearance and character, in south London. Did anyone mind?

When asked after his death whether she had any complaints about his behavior, Blake’s long-suffering wife Catherine tentatively mentioned an innate predisposition to spend a little too much time “in paradise.”

“I have very little of Mr. Blake’s company,” she said.

In recent years, Blake’s works have traveled quite far physically through the galleries of Tate Britain, the principal earthly depository of his delicate works in the United Kingdom. This spring, the London museum had a major re-hang. The last time this had happened was in 2013, under Penelope Curtis, its last director. That year, a dedicated Blake Room was created inside the Clore Gallery. The extension, which opened in 1987, was created to show off prized works from the enormous J. M. W. Turner bequest. Blake had his own little room carved out of it to show off a choice selection of his paintings and prints.

The walls were royal blue. The space was very dimly lit because works by Blake are so fragile and so light-sensitive. His pioneering use of mixed media makes them very unstable. They are often not on show for very long.

Was Blake thoroughly embedded in the 18th and 19th centuries? Only partially.

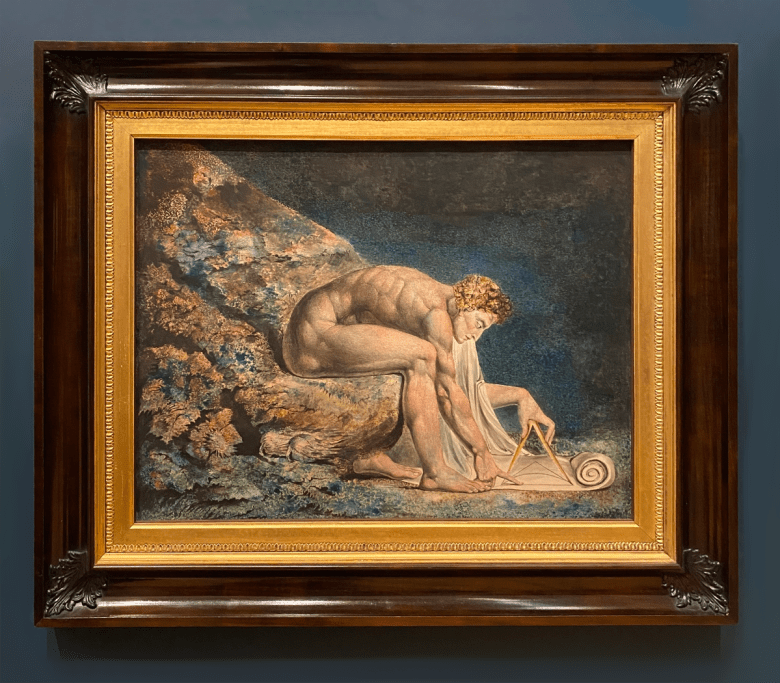

His prints, and especially those commissioned by clients, are often thoroughly neo-classical in feel and execution. But when he was let loose to make works of his own imaginings, he was a wild thing, a freelance mythologizer, a blazing forerunner of psychedelia.

This spring the Blake Room of 2013 disappeared from amongst the Turners, and 15 Blakes did a flit to the other side of Tate Britain, in the general direction of modernity.

This is a good decision. Turner and Blake had precious little to talk about.

Blake now lives in room 7 beside a gallery devoted to a selection of works by Chris Ofili, a contemporary painter upon whom he has had a huge influence. Ofili loves Blake’s use of color, his free-flowing line, and his unparalleled ability to conjure into fantastical beings.

This decision, at a stroke, tells us a lot about Blake and his posthumous fame and reach. He was always out of key with his times. This is why he was ignored, abused, and so thoroughly misunderstood during his lifetime.

In fact, Blake feels very close to the near present. The doors of perception opened up to him almost 200 years ago. Could Allen Ginsberg have written “Howl” without him?

I recall, as if it were yesterday, one rainy evening I spent in a giant marquee at the Hay Festival in the early 1990s. Ginsberg was sitting on a chair on the stage in front of me, squeeze-box bouncing up and down on his bony knees as he sang, with painfully exquisite tunelessness, a fragment of a famous verse from Blake’s Songs of Innocence: “…And all the hills echo-ed.”

He sang it over and over, over and over, over and over, and over.