Editor’s Note: This article was produced in collaboration with the Arts & Culture MA concentration at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

***

When the French-Malian multi-disciplinary artist Smaïl Kanouté came to New York in 2018 and noticed the words “Forever 21” blazoned above a storefront, he hit upon the title for the multi-pronged project he was working on at the time. The retail sign immediately brought to mind the men of color cut down by racism and gun violence before reaching that age. He decided on the title “Never 21” (2019) for his short film and related live dance performance piece, which paid homage to these men. The piece, which draws its vocabulary of movement from street styles like krumping and popping, premiered on September 27 at New York’s French Institute Alliance Française as part of the Crossing the Line Festival.

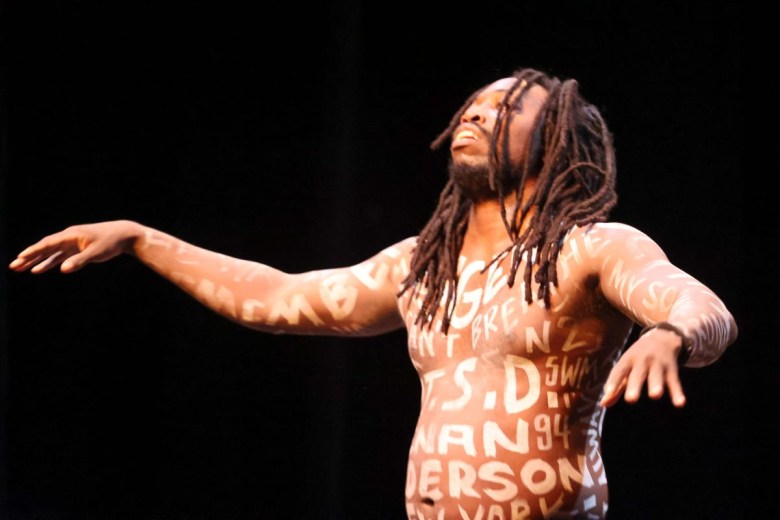

“Never 21” oozes rage and sadness with warranted intensity. Three male dancers combined jolting and at times graceful movement, honoring those lost to violence and reflecting on the anxiety they feel as Black men.

The piece began with the dancers, standing in darkness, shining flashlights onto the floor, scanning the stage at an accelerating pace as a soundtrack of disjunctive noise-music swelled. The stage was turned into a crime scene: Beams search for the body from an unsolved case.

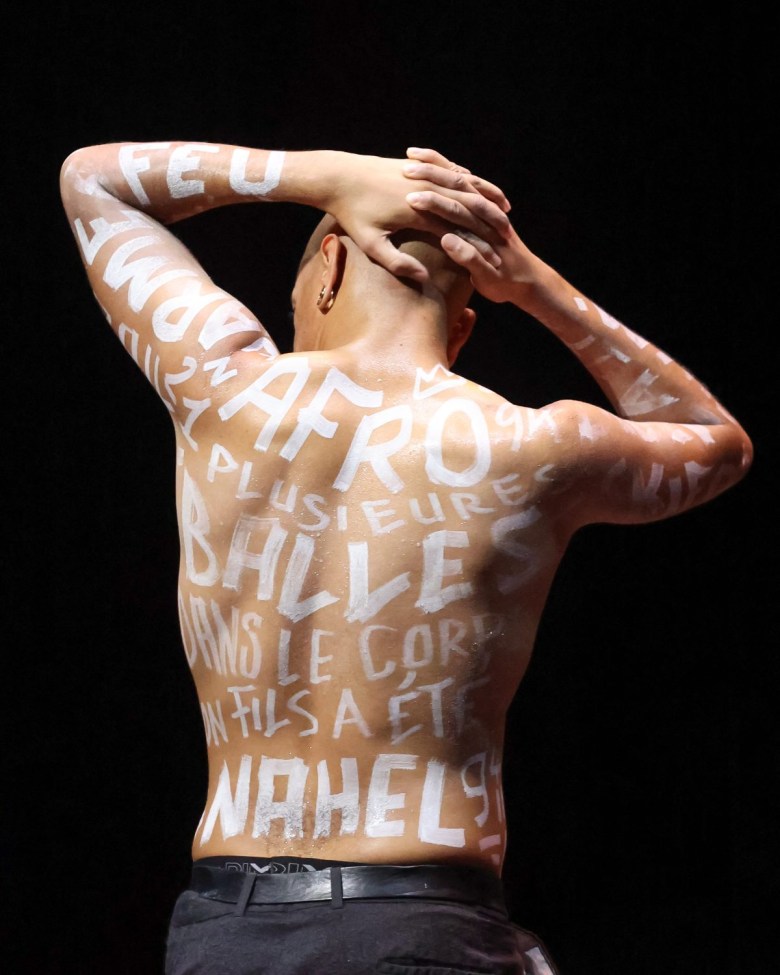

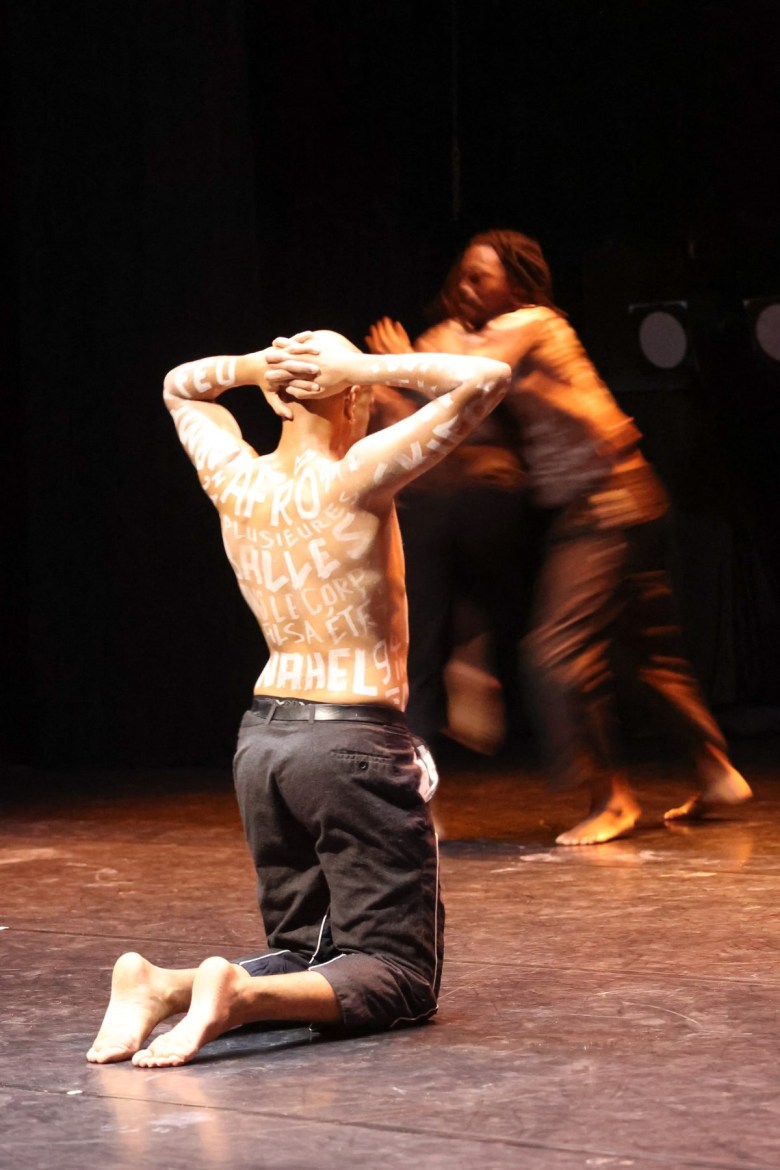

Soon, the lights left the floor and traveled across the performers’ bodies, revealing words written on their bare torsos and arms in white block lettering: “POLICE, GUNS, VIOLENCE, CRIME, DEAD, BULLET, BLOOD.” The men began spinning faster and faster to a disjointed rhythm until everything went black and fell silent.

In these opening few minutes of the performance, Kanouté established the piece’s compelling directness. The ominous words on the dancers’ bodies were mirrored in their heavy stomps, almost robotic arm movements, and sorrowful expressions.

A spotlight focused on a dancer sitting center-stage on a chair. In his stillness, more words on his body become visible: “INDIGENOUS, I CAN’T BREATHE, PASSING, DEATH, MEMOIR.” A raspy voice on the soundtrack described the senseless killing of a young Black man shot and killed by police. “He died so violently,” the voice said. “Every year I hurt.”

The speaker was one of seven heard throughout the performance, each a real person who lost a loved one to gun violence. Kanouté interviewed them as part of the research for his film, which led him across the globe to hear testimonies in English, French, and Portuguese. In “Never 21,” their words fused with the choreography to produce a palpable atmosphere of pain and grief.

Sometimes, there was an underlying delicacy and softness in the dancers’ movements — fluid arcs with their arms, ballet-like arched feet — juxtaposed against frequent harsh alarms and spasmodic choreography. This clash reflected an image of their struggle to live at once with tenderness and anger, youthful abandon, and heightened vigilance.

In the second half, the performance took on a narrative quality. A central scene takes place in a club, indicated by blue light and electro music. The three men greeted each other and traveled around the stage in unison. Two disappeared, leaving one in the center of the stage dancing to R&B. When the others returned, they beat him until he was left convulsing on the floor. Eventually, they dragged him off. I was gripped by Kanouté’s goal to demonstrate the undeniable oppression faced by Black men every day — which, he said in an interview with Hyperallergic, remained “underground” in France, his country of residence, until recently, when the death of Algerian- and Moroccan-French 17-year-old Nahel Merzouk at the hands of police in June sparked mass public protests against racial violence.

“Never 21” ended on an uplifting note: The men samba danced to Brazilian street music and voices speaking Portuguese. By this point, the sharp white words on their bodies had been near-erased by glistening sweat. The men kept dancing as the music faded.

Kanouté told me that he decided to close the show this way — in what he called a “Brazilian universe” — because he wanted to evoke the diverse and inventive subculture that he admires in the country; challenging political realities notwithstanding. “They have a powerful energy for life, and for creating,” he said.

Did Kanouté choose this ending because he was trying to imbue the viewer with a sense of hope? Perhaps, or maybe it’s not for us. Maybe it is for the three men on stage, whose own struggles as Black men pertain to the cause they dance for. It envisions a “Brazilian universe” where their brothers — and they themselves — live to see 21 and many years after.