Over the past six decades, Frederick Wiseman has steadily accrued one of the most significant bodies of work of any American documentarian. His methods of nonintrusive but exacting observation, combined with brilliant editing, have brought vital societal and thematic insight to his films about various communities and institutions. He’s looked at everything from a Chicago housing project to the workings of Boston’s City Hall, the labor of models, and London’s National Gallery.

After a COVID-precipitated break from nonfiction, Wiseman has returned with Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros. Over the course of four hours, we see the inner workings of La Maison Troisgros, a three-star Michelin restaurant in central France that’s been run by the Troigros family for four generations. Besides copious mouth-watering footage of various dishes being prepared and served, Wiseman watches the cooks and other restaurant staff as they plan menus, test new recipes, figure out where to seat guests, and gather ingredients from markets, the outdoors, and specialty vendors, among many more concerns. Despite the documentary’s length, it upholds a compelling portrait of restaurant logistics and the art that goes into food-making.

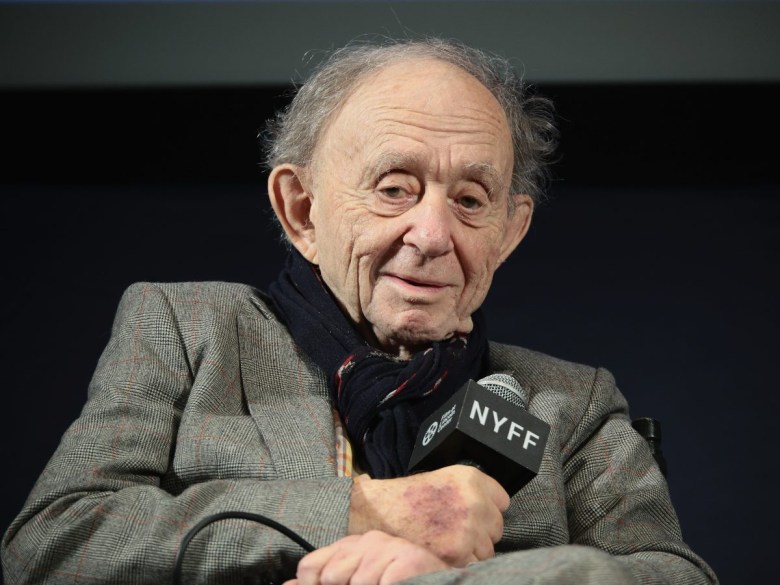

To discuss this art and logistics, we sat down with Wiseman for a conversation shortly after the film played at the New York Film Festival. He is currently enmeshed in an ambitious project to restore and digitize his older work. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

* * *

Hyperallergic: When this was announced, I was surprised when I realized that you hadn’t already made a film about a restaurant.

Frederick Wiseman: It had been on my sort of life list. There are lots of things that I haven’t done.

H: So there’s a list?

FW: I never talk about what’s on the list.

H: Fair enough. Is there any particular reason that this was the time to do the restaurant film?

FW: It was just sheer chance. In the summer of 2020, to escape the COVID in Paris, I stayed at various friends’ houses in the country. I spent a month in a friend’s house in Burgundy, and I wanted to find a way of thanking him and his wife, so I looked in the Guide Michelin for a good restaurant nearby and found Troisgros, which is about an hour away.

I invited them there for lunch, and at the end of the lunch, César, who’s a fourth-generation Troisgros, came out and sort of worked the room. He came to our table, and we chatted for a bit. Without planning to do so, I just blurted out, “I make documentary films. Would you consider having a documentary made about your restaurant?” He said, “Let me talk to my father.” And he came back a half an hour later and said, “Why not?” Then we exchanged some letters, and I went there on a visit. But the decision was basically made that day. Two years later, after I finished the film, I discovered that César’s father wasn’t there that day. Instead, he’d looked me up on Wikipedia and liked what he saw.

H: Do your subjects often manifest so spontaneously?

FW: Sometimes I think about something, but a lot of what I do is chance. I made Model because I was reading People magazine in my dentist’s office one day. I would never subscribe, but it’s always interesting to read the gossipy stuff. There was an article about a model agency. I was 48 at the time and figured that was a good time to make a movie about that. So I called up a couple of agencies in New York, and two of them said okay. I went to visit, and I chose one.

H: COVID broke the very long streak you had of releasing a film nearly every year. Last year you had A Couple, of course, but was it difficult to get back into the groove of your traditional way of making a movie?

FW: No, it wasn’t difficult. I didn’t like not working. It was the longest period in 53 or 54 years that I hadn’t started another film within weeks of finishing the previous one.

H: What made you feel it was the right time to work again? The vaccines?

FW: Yeah. I mean, COVID’s still going on, but it had diminished, and people weren’t wearing masks anymore. I waited until people stopped wearing masks, because I didn’t think it would be particularly interesting to not be able to see people’s faces. It wasn’t impossible to film earlier, but I think that without the opportunity to have closeups, which show the individuality of faces, it wouldn’t have been as interesting. I mean, no film would’ve been particularly interesting.

H: This was your first film with a new cinematographer in decades.

FW: Jim [Bishop] had been the assistant cinematographer on about 10 of my films, and John [Davey], for family reasons, wasn’t available last year. Jim knew the system.

H: How many people are involved in that system now?

FW: It’s usually three. This time it was four. I prefer to do the sound. I had a very good person doing it [Jean-Paul Mugel], but I physically couldn’t because I was sick. This is the first film that I didn’t do the sound for.

H: Will you be able to do the sound again in future films?

FW: I don’t know. I don’t know.

H: Does that trouble you at all, having to make these adjustments?

FW: Well, I’m glad I can continue to work. I’m not getting any younger.

H: Your films are usually about an institution or a community. This one, though, is about a family.

FW: Well, the restaurant is an institution. I mean, I have such a loose definition of “institution,” there’s no problem fitting the restaurant into it. It’s a small institution; the decision-making is happening in a smaller group. And in the film, you see how those decisions are made.

H: Besides your few visits to the restaurant, did you do any other preliminary scouting, research, or discussion on Troisgros and the other places we see in the film?

FW: No, I didn’t. Those visits were the only times I was there before the shooting. That’s my usual business. I don’t like to be there doing research and miss something. I’d be very upset if something great was going on and I was there just observing. Once I’m there, I like to be prepared to shoot, since none of the events are staged. If something happens and I’m not there, at least I don’t know what I missed.

H: What previous work informed the way you shot this film?

FW: Filming in a kitchen is like working with a ballet or theater company because you have to stay out of the way. They had a lot of quick movements, and they were repetitive movements; they did the same sorts of things every day. The restaurant is open for five days a week, two meals a day. They’re not always cooking, the menu isn’t always the same, but the same group of people was working there.

And so you have a chance to shoot it different ways, as I had a chance to shoot ballets in different ways. Either in the rehearsal or on the program for three weeks, you could shoot it one way and look at it and then shoot it another way, and then you could intercut. So it was similar in that regard to La Comédie-Française or my two movies about ballet. You could shoot wide shots one day and closeups the next. I could see whether I had what I wanted, and then go back and shoot it another way, or go back to a way that was originally shot if I found I didn’t have enough closeups of salmon being cut or whatever.

In addition to the contents of the recipes, they were equally concerned about the presentation, the way it looked on the plate. Like ballet, cooking at that level is an ephemeral work of art. With dance, there’s a great performance and then it’s over. With cooking, there’s a great meal and then it’s over. Movies or paintings are different because they’ll last a bit longer because they’re in forms that endure. But I think the artistic impulse behind the great chefs is the same as that behind a painter, a writer.

H: How did you arrange all the excursions outside the restaurant, to the market or the farms or the dairy? On different days, would the chefs say, “We’re going to do this,” and you decided to follow along?

FW: Yeah. Michel [Troisgros] would say, “I’m going to go to the goat cheese factory tomorrow. Do you want to come?” Or “A week from Tuesday, I’m going to the vineyard.” The answer was always yes. That’s typically what happens in all my films. The people who work there know much more about what’s going on than I do, and I encourage them to make suggestions. That gives me a wider latitude about what to shoot.

H: How long was this shoot? How did you know you had everything you needed?

FW: Seven weeks. It’s just instinct, a combination of instinct and experience. In the editing, I didn’t feel the absence of something I needed.

H: Has that instinct changed or refined much over time?

FW: I don’t know if that’s for me to say. I certainly think I’ve learned something about how to make these movies, having now made them for close to 60 years or god knows how long.

H: You’re in the process of restoring and recoloring your older films, everything on prints. I read in an earlier interview that you don’t tend to rewatch them once they’re done. What has revisiting them all been like?

FW: Yeah, it’s rare that I see a film once it’s finished. But obviously, for this you have to. It’s fun, actually. It brings back all kinds of memories of the shoot. I see things that I like. I see mistakes that I made. It’s a trip down memory lane. I had 32 films that were shot on film. Basically, they couldn’t be shown anymore in theaters because they don’t have 16mm projectors. I got a grant that paid for the digitalizing. They were never digitalized before.

H: Are you going through them in chronological order?

FW: No. I do the color grading after the technical person has cleaned the films and made a first pass. Then I come in and finish the correction. I pick from whatever is ready. Right now I’m working on Belfast, Maine.

H: Do you find that the digitization makes any difference in the quality of the images?

FW: No, I don’t. It’s mainly a question of enhancing the original grading. You can be much more precise with digital grading. On film, you assigned a shot a light value, and that was it. With this, if you want to make the sky a little bit grayer or a shot a little brighter, you can do it. If somebody’s sneakers look a little faded, you can change it.

H: Some filmmakers have really resisted the change to digital.

FW: There’s a lot of bullshit about the transition. I preferred — and I still prefer — both shooting and editing on film, because I worked on film for so long. But it was a question of finding laboratories. There aren’t many good ones anymore. It’s less expensive — not a lot less, but somewhat less — to shoot digitally. The editing still takes me about 10 months. You can recover material faster, but it’s not necessarily an advantage. When I was editing on a Steenbeck [editing table] and I had to take the time to find things, I was also reviewing material. While it’s nice to go boom, and the shot appears, the real job of editing is not the mechanical part. It’s what goes on in your head.

Where will it be possible to view this documentary? Will it be shown on TV? I am very excited to see the end result., but do not live in NY or a major city. This is not a comment to post, only a request for information.