The origin story of Jay DeFeo’s monumental painting “The Rose” (1958–66) is by now a well-worn legend. After building up its surface layer by layer for nearly a decade — long enough for the piece to go through distinct stages, its title changing along the way — DeFeo could only remove it from her studio by knocking out an exterior wall and extricating it with a forklift. “The Rose” was exhibited in 1969 before it was famously sealed behind a wall at the San Francisco Art Institute (where DeFeo taught) for more than 20 years, awaiting preservation. The painting was delivered via a second architectural C-section in 1995, when it was taken to its present-day home at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The rest of DeFeo’s career has been overshadowed by this narrative, leaving other bodies of her work pushed to the wayside and forgotten — in some cases, very literally.

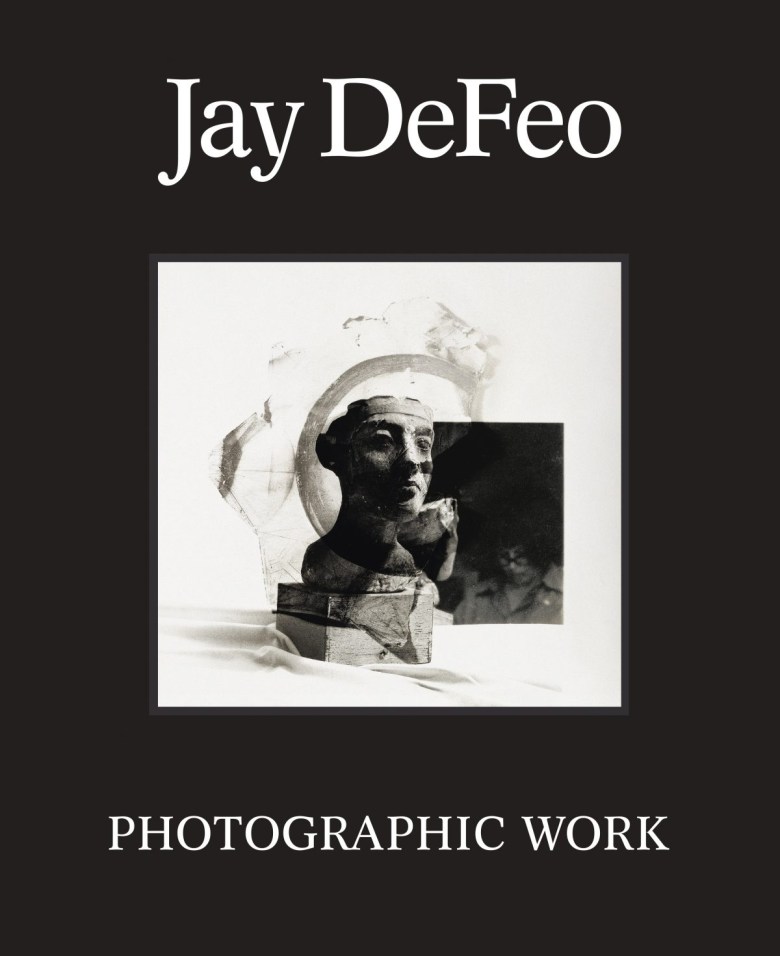

When the Jay DeFeo Foundation opened some of the late artist’s archive boxes, which they believed contained her papers, they uncovered something else: decades’ worth of photographs. This discovery has led to a third exhumation of her oeuvre, culminating in a new monograph, Jay DeFeo: Photographic Work, and a recent exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery. The book features texts by an impressive collection of authors, including Hilton Als, Corey Keller, Dana Miller, Catherine Wagner, and Justine Kurland (who has curated a concurrent exhibition in homage to DeFeo at the Lumber Room in Portland, Oregon). Together, they demonstrate that DeFeo should be seen as a major figure in contemporary photography.

DeFeo photographed throughout her life but practiced most intensely in the first half of the 1970s, after setting up a darkroom at her home in Larkspur, California. While the artist never received a formal education in the medium, she learned from her colleagues in the photography department at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) and adopted an experimental, process-focused style that differed from the dominant “pure” photographic look of the era. DeFeo liked to blur the lines between painting and photography, photographing her paintings and painting light onto her photographs with darkroom chemicals.

The work is heavily indebted to Surrealism, an influence that DeFeo openly acknowledged; in a group of images collectively titled Salvador Dalí’s Birthday Party (1973), she painted chemicals onto light-sensitive paper, creating amorphous, dreamlike landscapes that appear to melt like one of Dalí’s clocks. Most significantly, she discovered an artistic kinship between herself and the Surrealist group’s chief photographer, Man Ray, who valued experimentation over technical perfection. To DeFeo, Man Ray’s explorations of photographic abstraction must have read as a liberation, justifying her impulse to build up the material texture of her images and embrace chance in the darkroom.

But the dominant Californian movement toward “straight photography” during that era was hardly lost on DeFeo. Its influence is most evident in her botanical still lifes: in one untitled 1972 close-up of a plant leaf that recalls the work of Edward Weston, she faithfully captures each hair of its stem, rendering it in detail on the final print. Even more radical, however, is the print’s inclusion of tiny hairs not present on the plant itself, nor anywhere in the original scene. DeFeo did not retouch her prints, which means that the bits of dust caught by the negative in the printing process were registered in the final image. Every print she made was unique. Those who adhered to the “straightest of straight photography” likewise refused to retouch their final prints, but toward a different end. Rather than trying to depict the world directly, she embraced photography’s materiality, its existence as an object; instead of trying to erase the ways in which the camera lens mediates the world, she held them up for us to see.

Jay DeFeo: Photographic Work, edited by Leah Levy, is published by DelMonico Books and is available online and at bookstores.