Religion influenced modern art’s development far more than most accounts let on, and some of today’s most iconic artists mined their spiritual practices as sources, including Andy Warhol and Joseph Cornell. Contrary to popular belief, God is not dead. Alas, art historians and art critics have buried the lead, glossed it over, or outright ignored this influence. Erika Doss’s new book Spiritual Moderns bravely retells the story of modern art, fraught as it may be, with a more honest look at how religion shaped it.

The book takes place amid a tectonic shift: The mainstream art world is becoming more open to spirituality and religion. In 2019, before the pandemic, Swedish mystic artist Hilma af Klint shattered the Guggenheim’s all-time attendance record, bringing in around 600,000 visitors. In 2018, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute presented a show on the Catholic imagination in fashion. In 2019 and 2021, the Brooklyn Museum and the Andy Warhol Museum jointly put on the first institutional show on Andy Warhol’s religious beliefs. The late modern art critic Clement Greenberg must be rolling in his grave. A certain anti-religious bias — once de rigeur in the art world — is fading but not yet entirely gone. It still distorts how we retell many important stories in modern art history. Erika Doss now attempts to correct the record.

“How do we actually do this? What is a methodology that we can use to look at religion and modern art?” Doss asked rhetorically in an interview with Hyperallergic. Although art history employs a refined methodology to discuss religious symbols in works by the Old Masters, the connection between religion and the avant-garde is relatively undertheorized. Vague allusions to Vasily Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in the Art (1911) function as a smokescreen concealing deeper unresolved epistemological quagmires in general, and to some extent in the book. Through a series of four case studies, along with an intro and conclusion, Doss exposes how earlier historians of modern art have downplayed religion as a key ingredient in some of modern art’s most heralded breakthroughs.

Inevitably, Doss’s introduction had to first answer the tricky questions of “what is modernism?” and “what is religion?” Alas, her approach to both was too diplomatic, perhaps revealing how her editor and prestigious publisher might cling to outdated notions of academic neutrality.

In attempting to define modernism, the introduction did not go far enough to indict the toxic feedback loop between which modern artists break records on the auction block, what hangs in collector’s homes, and whom curators then spotlight in museums. That loop generates a “canon” of modern art, which has left out some of the artists she spotlights despite their historical influence and critical acclaim.

Religion’s definition is deeply contested with theologians, philosophers, anthropologists, psychologists, historians, rabbis, priests, monks, imams, and mystics all seeking to shift the terms of debate. There is, quite simply, no precise agreement upon what religion is or its first principles. Rather than gingerly stepping around these conflicts with a smorgasbord of primary source quotations to offer context, it could have been illuminating to forthrightly discuss these tensions. Perhaps the editors reasoned that digging into this debate would lead the reader too far away from the art history they ostensibly signed up for.

These quagmires lead Doss towards four discrete case studies, instead of attempting something more systematic. And it is here that her strength as a historian shines bright. The following four juxtapositions illustrate the main subjects of Doss’s new book: Andy Warhol, Mark Tobey, Agnes Pelton, and Joseph Cornell. These comparisons make a vivid case for modern art’s extensive interconnections with religious and spiritual currents, but also reveal the underlying methodological debates that will need more theorization.

Growing up as a Byzantine Catholic, Andy Warhol experienced sacred images at church in a profoundly different way than Roman Catholics or Protestants. The Byzantine rite is a unique Catholic community that originates in Ukraine. Holy Angels Byzantine Catholic Church in San Diego demonstrates that Byzantine Catholic visuals are more akin to Eastern Orthodox ones. The church is similar to Pittsburgh’s St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church, which the young Warhol attended. The iconostasis — the screen of icons that forms the focal point of liturgy — features the seriality and repetition that would become mainstays in Warhol’s artwork.

In the theology of icons, a church’s particular icon is experienced as a “copy” of a sacred prototype image. In a similar vein, Warhol had a sharp eye for finding images in modern life that were ripe for repetition and revisiting. Just what is it about Jackie Kennedy or Marilyn Monroe that makes us want to keep looking again and again? Perhaps it is easier to tell the story of Warhol’s struggle to reconcile his queer sexuality with a dogma of homophobic hate. It is harder and less familiar to show how Warhol’s repetitive pop sensibility resonates with the semiotics of icons. The history of the icon boasts an extensive museum in Athens, but only an alcove at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Louvre. Doss’s Warhol chapter rightly chose this harder path, challenging all of us to start talking about Warhol in a way that centers the influence of icons.

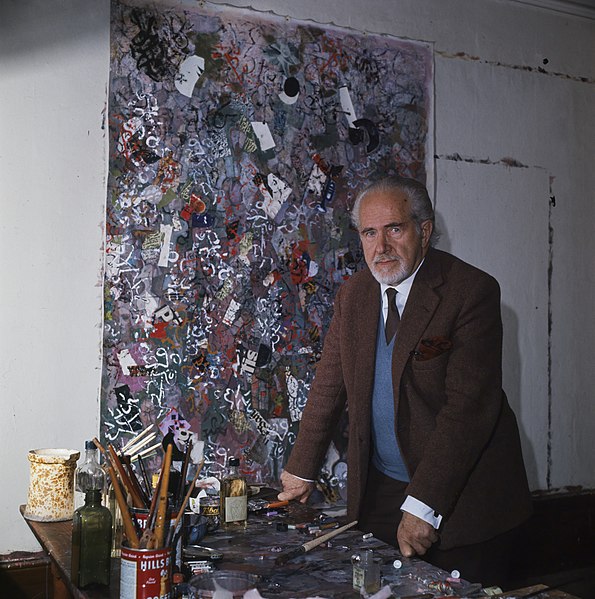

Mark Tobey is far more important than current museum shows and auction prices let on. As a deeply spiritual gay man who worked in several eclectic styles, he was never going to be Clement Greenberg’s number one. But the inconvenient truth is that Greenberg’s number one, Jackson Pollock, got the inspiration for his legendary drip paintings from looking at Tobey’s signature “white writing” technique. No one in the 1950s was going to tell the story that the queer mystical artist Tobey got there first, long before the burly Pollock. Although critics like Rob Weinberg recently acknowledged Tobey’s influence on Pollock, and the documentations of their encounters are indisputable, it is still hotly debated because Pollock was too macho to say it himself.

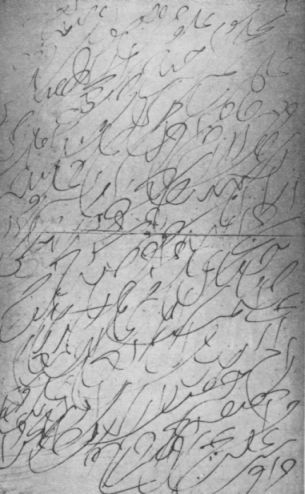

It’s clear that Tobey’s painterly scribbling owes some kind of debt to calligraphy. However, the dominant art historical discourse has generically attributed it to non-Western calligraphy and egregiously left out his deep and specific engagement with Baháʼí calligraphy. Doss addresses this overlooked connection. Early followers of Baháʼu’lláh, who founded the Baháʼí Faith, wanted to record his revelations and developed a unique shorthand, which is far loopier and chaotic than most Persian calligraphy that preceded it. As Mark Tobey became a devoted Baháʼí, his encounters with this shorthand undoubtedly shaped his “white writing,” with its sporadic, frenetic quality. The vexing problem is many art critics are not cognizant of the nuances of Baháʼí calligraphy, so the chain of influences isn’t clear. There would arguably be no Jackson Pollock drips if not for Baháʼí calligraphy — and Mark Tobey as the link between them. If you’re bristling, it’s because the bias that modern art developed outside any religion’s influence is deeply entrenched. Why are we betraying the foundational art historical methodology of honestly identifying and naming sources for formal innovations?

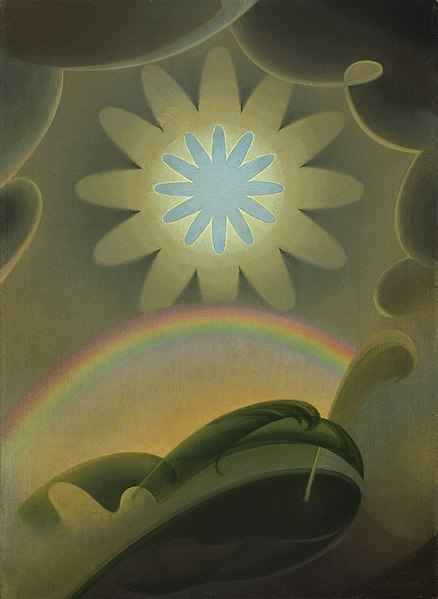

It was inevitable that one case study would venture into the occult, astrology, yoga, and theosophy, which influenced so many avant-garde artists. Here Doss examines the life and work of modernist artist Agnes Pelton, who drew upon all of these sources to create unabashedly occult images. Her work was dismissed as mystical for years but is being reappraised in this new epoch.

Theosophy was a 19th-century movement begun by Helena Blavatsky, which appropriated some ideas from Hinduism and Buddhism, and eclectically mixed them in with the preexisting Western occult traditions of alchemy, hermeticism, and Neoplatonism. She then topped it off with a heavy dollop of Orientalist frosting, serving it to Western renegades disillusioned with Christianity. Blavatsky was born in the city of Yekaterinoslav, then in the Russian Empire. Today, her birthplace is known as Dnipro, which remains part of Ukraine despite the current war. Although the Theosophical Society today remains relatively small, its influence on several artists was immense.

There is a clear affinity between Agnes Pelton’s painting “Sand Storm” (1932) and the illustration of the Crown Chakra in C.W. Leadbeater’s The Chakras (1927), the book that introduced the chakra system to the United States and Europe. As modern artists of the early 20th century sought to find new forms, many like Pelton turned to theosophical texts and their unusual illustrations.

Like Frida Kahlo, Joseph Cornell is often crudely lumped in with the Surrealists, when his life and work followed a trajectory far away from André Breton. The real story is that Joseph Cornell was a Christian Scientist and often introduced himself as such to many people in the art world. Doss’s chapter convincingly shows the concept of “unfoldment” is a far more essential ingredient in Cornell’s work than surrealism’s faint echoes.

As DeWitt John once wrote, “In Christian Science the word unfold has special meaning. It means to express, to show forth, to develop and display, to bring out what is real in its fullness.” This process is concretized in the window displays and window boxes of many Christian Science reading rooms, which invite viewers to slow down, look, read, and allow something to unfold within their minds as they reflect upon what they perceive. There is a similar unfolding in Cornell’s boxes that invites viewers to ponder and allow the connections between the disparate pieces to sink in. For example, in Cornell’s “Blue Soap Bubble” (1949–1950), the viewer is invited to slow down and unfold the connections between the glassware, the Angola stamp, and the celestial images. When Mary Baker Eddy founded Christian Science in the 19th century, unfoldment was one of the numerous concepts she introduced to facilitate healing and mental clarity as an alternative to other Christian sects, such as the Baptists, Congregationalists, Methodists, Anglicans, or Lutherans. Doss demonstrates how Cornell’s work invites the viewer into this slower gaze of unfoldment and to draw out unanticipated connections.

College students often grumble that introductory art history courses feel like Sunday School. How much of the Bible do they need to know to get Giotto? Many breathe a sigh of relief when modernism comes along and frees them from religious symbols. Nevertheless, it’s an error of omission to discuss Warhol without icons; Jackson Pollock without Mark Tobey and Baháʼí calligraphy; spiritual artists like Agnes Pelton without the influence of theosophy; and Joseph Cornell without Christian Science. It doesn’t help that Byzantine Catholicism, Baháʼí, Theosophy, and Christian Science are not the predominant faiths of today’s art collectors and museum patrons. In presenting these four case studies, Erika Doss indicts the theological laziness at the heart of most accounts of modern art. The facts — inconveniently — lead somewhere else.

Spiritual Moderns: Twentieth-Century American Artists & Religion (2023) by Erika Doss was published by the University of Chicago Press and is available online and in bookstores.