LOS ANGELES — Long before reality television series like the ever-popular Naked and Afraid, true crime shows, and WWE and MMA extravaganzas entertained millions with the suffering (whether feigned or authentic) of others, there was the wildly popular yet short-lived phenomenon of dance marathons in the 1920s and ’30s.

Throngs of paying customers watched contestants dance to the point of slumping exhaustion, or worse — not just for hours, but for days, weeks, even months. One couple would eventually win the top prize (which could be a considerable sum in those days) while all others fell by the wayside, sometimes literally; medical personnel were on site. This weird fad began in the ebullient Jazz Age but assumed far grimmer significance during the Great Depression, with desperate people competing for cash.

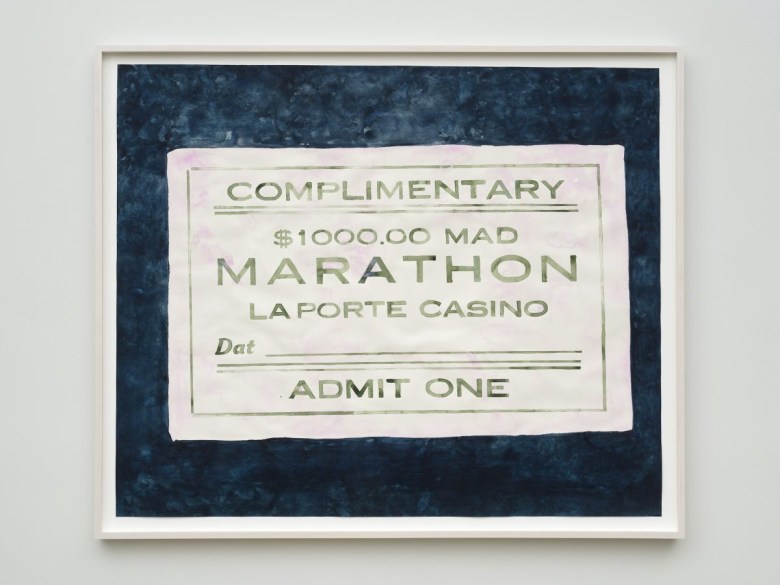

These marathons have long been a potent theme for Kambui Olujimi, whose eclectic work spans sculpture, installation, performance, painting, and other mediums. The eight engrossing paintings (all watercolor, ink, and graphite on paper) and two ceramic sculptures (all works 2023) in his memorably titled exhibition All I Got to Give — his first with Susanne Vielmetter gallery — turn dancing couples, admission tickets, trophies, and, more implicitly, audiences into complex, extremely pertinent meditations on endurance, fragility, care, resistance, transcendence, and — importantly — race.

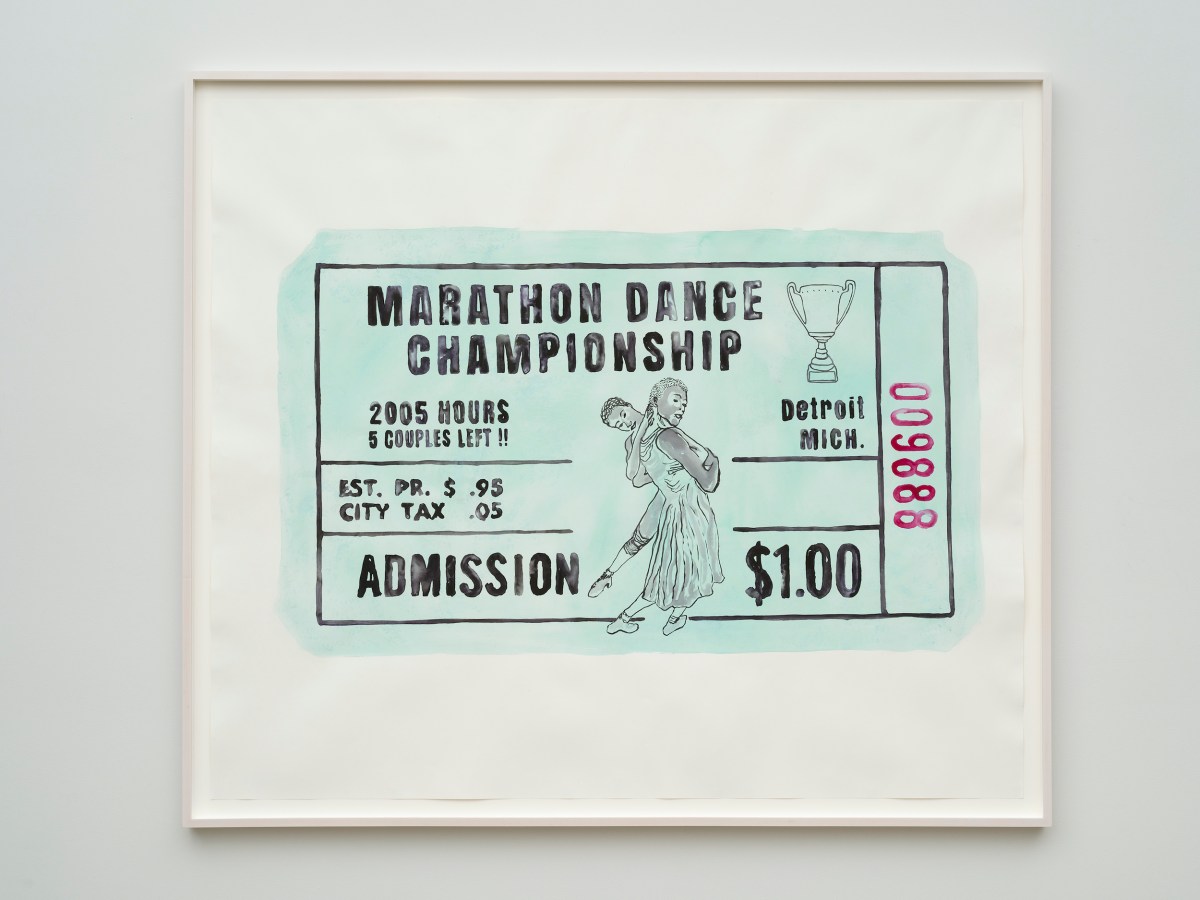

The introductory painting is an outsize, handmade rendition of an admission ticket from way back when in “Detroit, Mich.,” as it says on the ticket (“Champion Ticket”); like so much else in the United States of those times, dance marathons were strictly segregated. A Black couple seems buoyant and graceful, yet the words undercut the pleasant image: “2005 HOURS” (more like sustained torture than dancing), “5 COUPLES LEFT!!” (gruesomely Darwinian).

Nearby is the startling image “Still Standing,” with the emphatic title words, rendered in both black and white, seemingly reverberating on a dark, smudgy background replete with what look like hovering eyes and flashes of light, maybe from cameras. These words are at once straightforward and defiant. Still standing in America after, well, everything.

In “Props,” with its multiple meanings (Olujimi can be quite a wordsmith), two bone-tired dancers still tenderly support one another; they are vulnerable but also stalwart and full of care. Bursts of light in the background suggest camera flashes but also stars. This dance hall scene becomes cosmic.

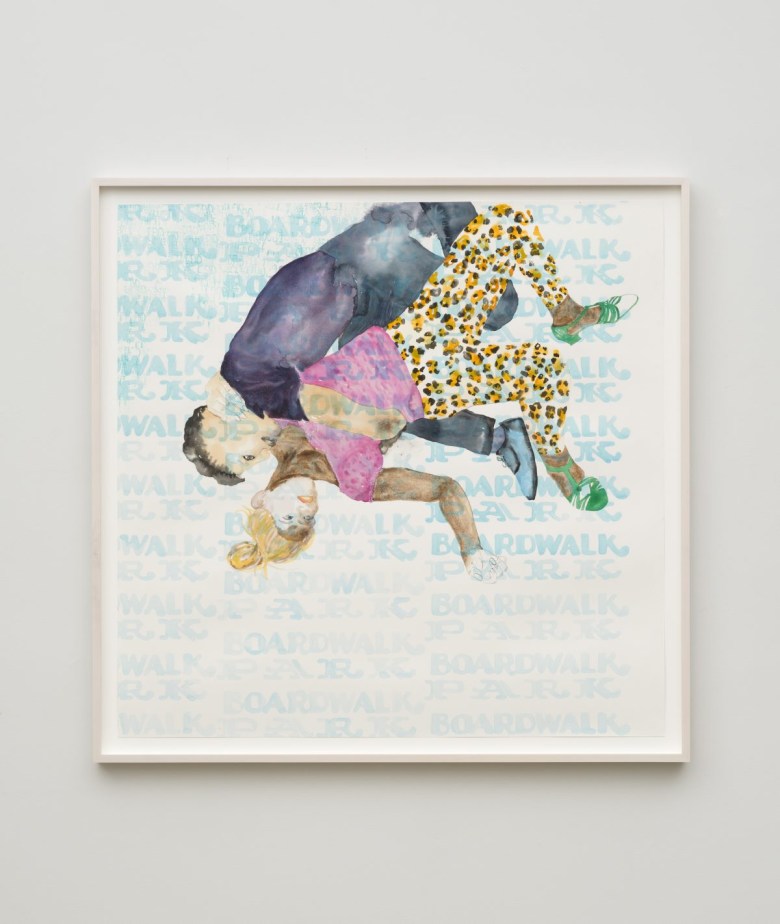

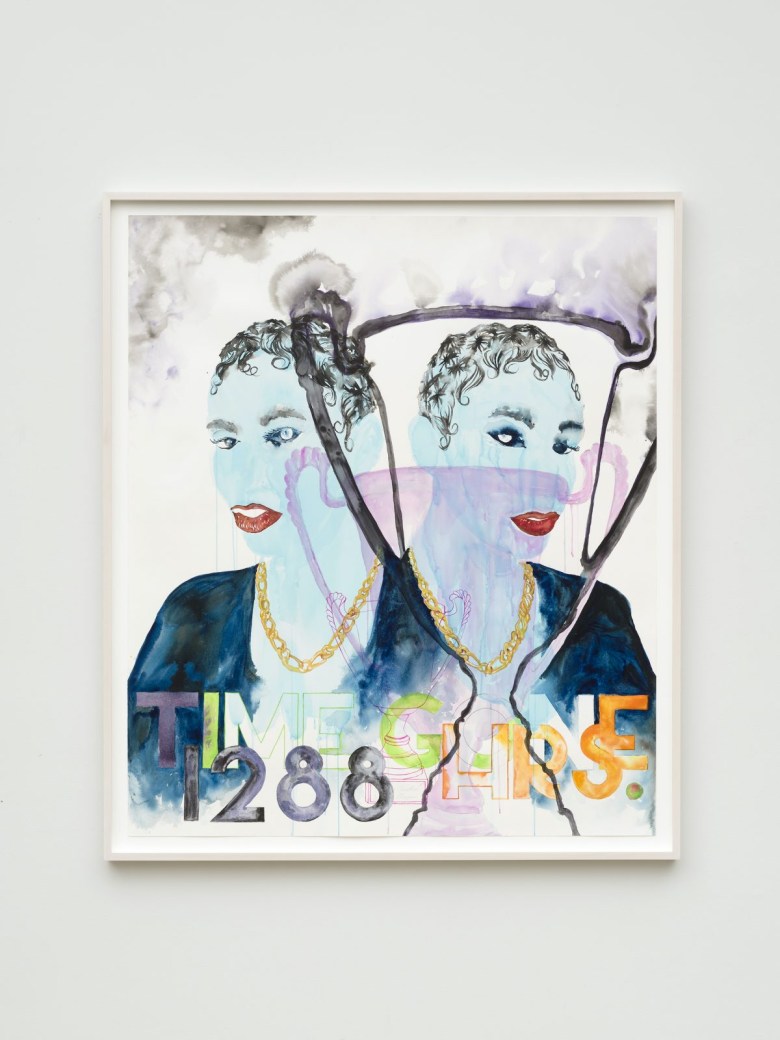

Olujimi’s paintings are often exquisite, including the dancers’ nuanced expressions, and color is a judicious yet dynamic force, however they are also willfully scruffy, with drips, stains, scrawls, and smears. Grace and elegance abound, but so too do rugged drama and discomfort. One couple — she’s in leopard print pants, a pink top, and green shoes; he’s in blue shoes, gray pants, and a purple shirt — could be asprawl but also aloft, twining together in aerial exuberance (“Boardwalk Float”). Enveloped by numbers, two upright yet sagging dancers are extraordinarily thoughtful and tender in each other’s arms (“Peacock Numbers”). Like most of Olujimi’s figures, they are also mobile in time, maybe existing decades ago, maybe right now. A bit of research reveals that the Peacock Ballroom in Portland, Oregon, famous for its marathons and walkathons, was also infamous for its discriminatory practices and abuse of contestants, including children.

Ceramic sculptures of trophies are hardly flawless and sleek. Instead they are handmade, irregular, and a bit ungainly, even precarious, as if imbued with, and honoring, the extreme physical effort and emotional struggle of the dancers. Accessing an obscure and bizarre historical oddity, Kambui Olujimi’s exhibition is also spot on for our own troubled times.

Kambui Olujimi: All I Got to Give continues at Susanne Vielmetter (1700 South Santa Fe Avenue #101, Downtown, Los Angeles) through December 23. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.