LOS ANGELES — Food has played a central role in Islamic societies for hundreds of years, with ideas about hospitality, community, identity, class, and leisure finding expression through the gustatory traditions and accoutrements of courts throughout Southwest Asia, North Africa, and beyond. Dining with the Sultan: The Fine Art of Feasting at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is a historic survey of these culinary cultures and customs, featuring 250 objects from Iran, Turkey, Syria, Iraq, India, and elsewhere. The exhibition predominantly features tableware, serving vessels, and dining accessories, but also paintings, recipe manuscripts, textiles, and musical instruments complemented by an 18th-century reception room from Damascus on view in the United States for the first time and a contemporary installation by Iraq-born artist Sadik Kwaish Alfraji.

“Food is a great way to introduce an American audience to Islamic art and by extension to culture,” exhibition curator Linda Komaroff told Hyperallergic. “I like to do exhibitions that are not so much focused on a particular medium or dynasty, but on a universal theme.” In keeping with this idea, the show is divided into thematic sections such as “Outdoor Feasting and Picnicking,” “Coffee Culture,” and “Dressing for Dinner,” areas of interest that cut across eras and regions.

One way in which Komaroff has made the show more accessible is through a “virtual meal” located in one of the exhibition galleries, which features a traditional sufra, a round cloth covering a low, communal table at which visitors are invited to sit on cushions before a menu and a surprisingly realistic facsimile piece of puffy, round bread. On screens embedded in bowls on the table, images of six dishes prepared by Iranian American chef Najmieh Batmanglij float by: Badhinjan mahshi (eggplant dressed in sauce), zereshk palaw ba gusht (rice and lamb with chickpeas and barberries), and a khagina (sweet omelet) among them. Online video tutorials offer museum-goers the chance to recreate the dishes at home.

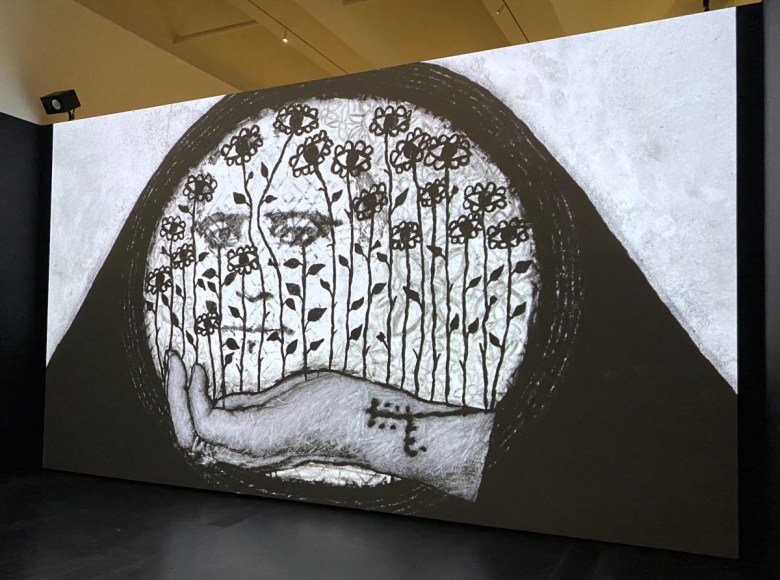

“This circle of the sufra, where we sit together to eat on the floor, it is not only a time of eating, it is also a time of love, gathering, happiness, and this warm feeling of family,” artist Sadik Kwaish Alfraji told Hyperallergic. “Sitting in a chair is different from sitting on the floor — everything will be next to each other, your knee will reach the knee of your brother or father. When you eat, you share the same dish. It’s very special.”

That sense of communal gathering and hospitality is also felt in the impressively restored Damascus Room, a sumptuously decorated reception room from a late-Ottoman-era courtyard home built between 1766 and 1767. The 20-by-15-foot room features painted and carved wood walls, the upper portions of which are covered in calligraphic poetry verses; a stone fountain; and a soaring arch that separates the lower reception area from a raised seating area lined by cushions. The room is missing its wooden ceiling and clerestory stained glass windows, though the latter have been approximated with colorful projections.

The house it was part of was slated for demolition to make way for new roads in the 1970s. In 1978, it was sold to an antiques dealer, disassembled, and shipped to Beirut, where it languished for decades. After arriving in London in 2011, it was acquired by LACMA in 2014, undergoing four years of restoration and conservation. It was finally mounted on a metal framework, making it the “first-ever portable Damascene period room.”

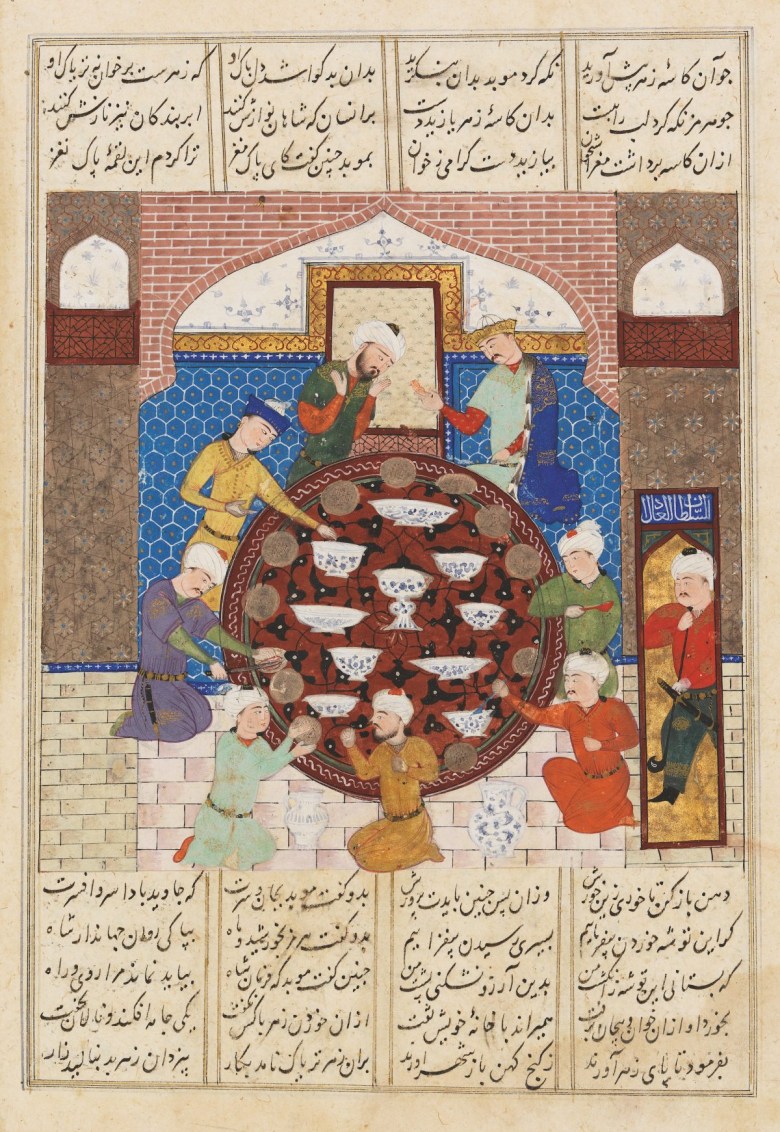

As much as the objects in the exhibition convey culinary traditions unique to Islamic cultures, they also depict networks of aesthetic and cultural exchange. The show features Italian maiolica, tin-glazed pottery featuring colorful scenes on a white background, that Komaroff explained were influenced by Islamic lustreware coming through Spain. It also includes several examples of ceramics exported from China. “In most of the courts — Mughal, Safavid, Ottoman — the rulers dined on imported Chinese porcelain. if you look carefully at paintings and illustrations, you’ll see Chinese porcelain being depicted, and blue and white reinterpretations of it made locally,” Komaroff said.

Alfraji’s animated video installation “A Thread of Light Between My Mother’s Fingers and Heaven” (2023) also tells a story of migration, albeit with an aura of loss. He moved from Iraq to the Netherlands in the 1990s, and his piece is like a hazy recollection of familial warmth. Black-and-white images appear and are replaced by others, leaving palimpsests behind: his mother’s hands, flowers, a communal meal, and the mythological winged creature with a human head and horse’s body.

“When they told me about the concept, I immediately thought about my mother’s fingers as she made bread,” he said, calling back to a formative memory that spans all five senses. After living abroad for so many years, has he ever been able to find a bread that can stand up to his mother’s, that can provide the same sense of warmth and connection? “Never, always there is something missing. The touch of my mother’s hand, the feeling when I’m watching her making bread, she takes it out of the oven and I just take it from her hand and eat it. That gives it a kind of taste that I haven’t found anywhere.”