Renowned metal sculptor Richard Hunt, celebrated for his near 70-year artistic practice rooted in civil rights, the natural world, and cultural dynamism, died in his Chicago home last Saturday, December 16 at the age of 88. The artist is survived by his daughter Cecilia and his sister Marian.

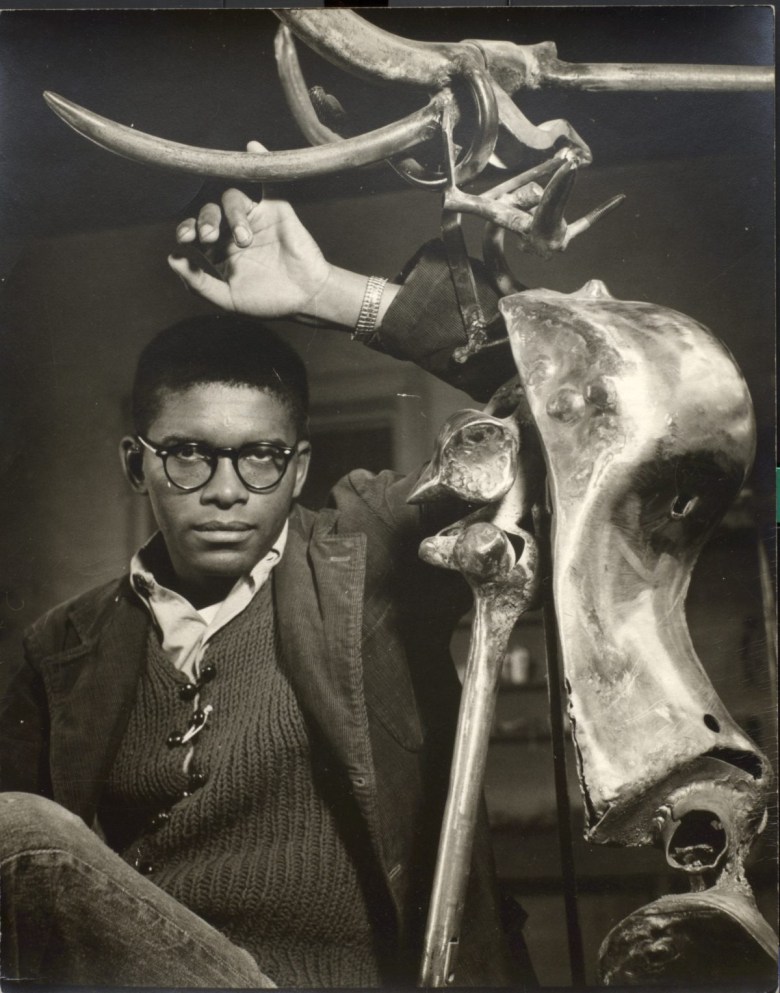

Hunt, whose metallic forms and public monuments are now displayed across the United States, began to pursue his artistic interests at an early age, enrolling in local art classes in Chicago’s South Side as a child. He later completed his undergraduate studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) in 1957 with a concentration in sculpture, and was deeply fascinated with the work included in the AIC’s 1953 exhibition Sculpture of the Twentieth Century.

Speaking of his fixation with his chosen medium, Hunt told the Copper Development Association that he “think[s] in metal” as though it were a language, adding that “there’s a relative ease of fabrication, manipulation and longevity, and ease of maintenance that’s built into the material itself.”

At age 19, Hunt’s conceptual practice was forever reshaped in 1955 after he attended the public, open-casket funeral for Emmett Till, a Black American teenager who was kidnapped, tortured, and lynched in Mississippi over a false accusation. Till was raised only two blocks from Hunt’s birthplace and was killed while visiting extended family down south, prompting the artist to reorient his artistry toward civil rights and expressions of the Black American experience.

As a welder who initially sourced his materials from vehicle junkyards and curbsides, Hunt made history when he became the youngest artist to exhibit his work at the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle. The artist’s upward trajectory was marked by many firsts: In 1968, he became the first Black artist appointed to the National Council on the Arts, and at age 35, in 1971, he became the first Black sculptor to secure a solo retrospective in 1971 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which had acquired his sculpture “Arachne” (1956) in 1957.

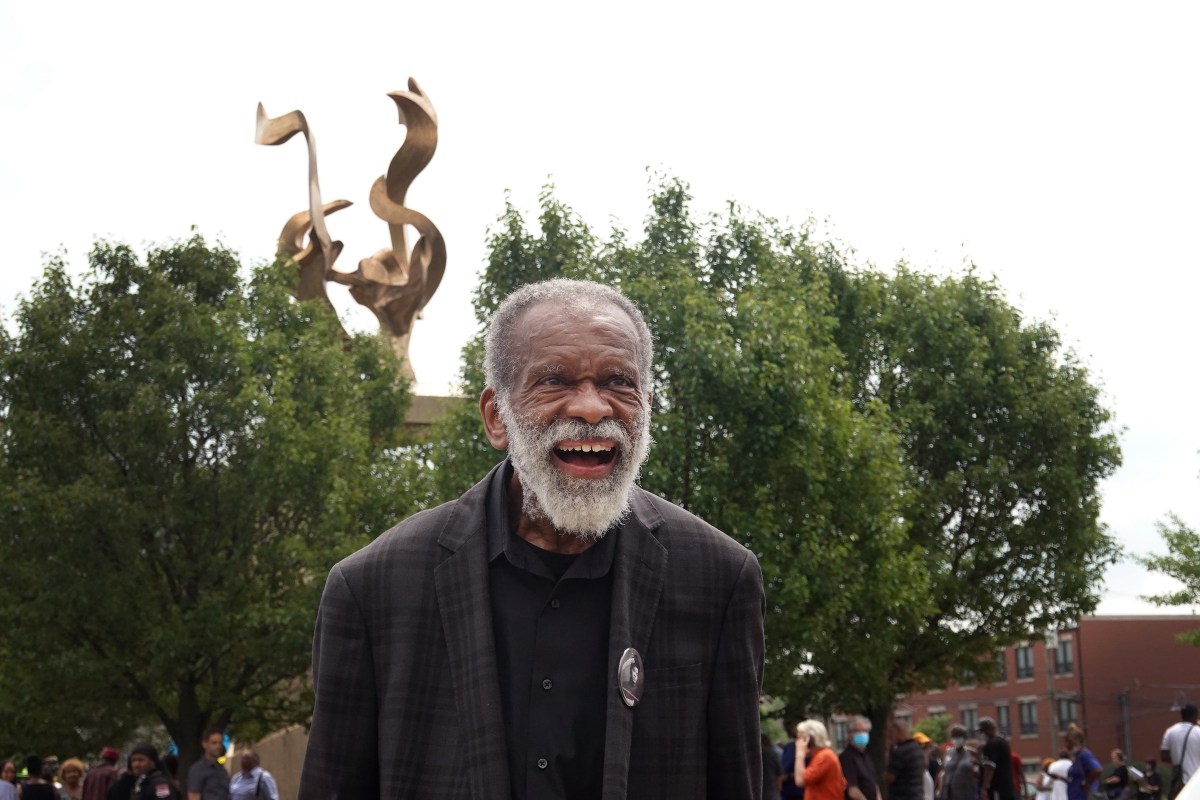

The artist’s debut public art commission “Play” (1967), installed at the John J. Madden Mental Health Center in Maywood, Illinois, launched a regular flow of requests for commissioned monuments and sizable public works that necessitated collaborations with factories and engineers. Among his most well-known public sculptures are “Swing Low” (2016) at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, and Flight Forms (2001) at Chicago’s Midway International Airport.

Hunt spearheaded 160 public sculptures commemorating notable happenings in Black history as well as Black American heroes in education, civil rights, and sports throughout his career, including journalist and activist Ida B. Wells, attorney Hobart Taylor Jr., and track and field athlete Jesse Owens.

Despite his frequent focus on specific historical figures, his biomorphic forms infused with suggestions of spirituality and mythology were decidedly abstract at a time when some Black artists chose to focus their efforts on figurative art. “I am interested more than anything else in being a free person,” the artist said of his practice, per a statement from his gallery. “To me, that means that I can make what I want to make, regardless of what anyone else thinks I should make.”

The influence of Emmett Till’s murder on Hunt will come full circle as one of the artist’s final creations was the model for a monument titled “Hero Ascending” (2023) that will be installed outside of the Emmett and Mamie Till-Mobley family house in Woodlawn next year.

A public celebration of Hunt’s life and legacy will take place in Chicago in spring of 2024. In the meantime, the artist’s website has an exhaustive list of his public commissions across the states, and his first solo exhibition as a newly represented artist at White Cube is still slated for March as planned at the gallery’s New York location. The show will include works from the first two decades of Hunt’s career as well as pieces from the artist’s personal collection.

Park in Memphis, Tennessee (image courtesy Jon Ott/Richard Hunt Legacy Foundation)