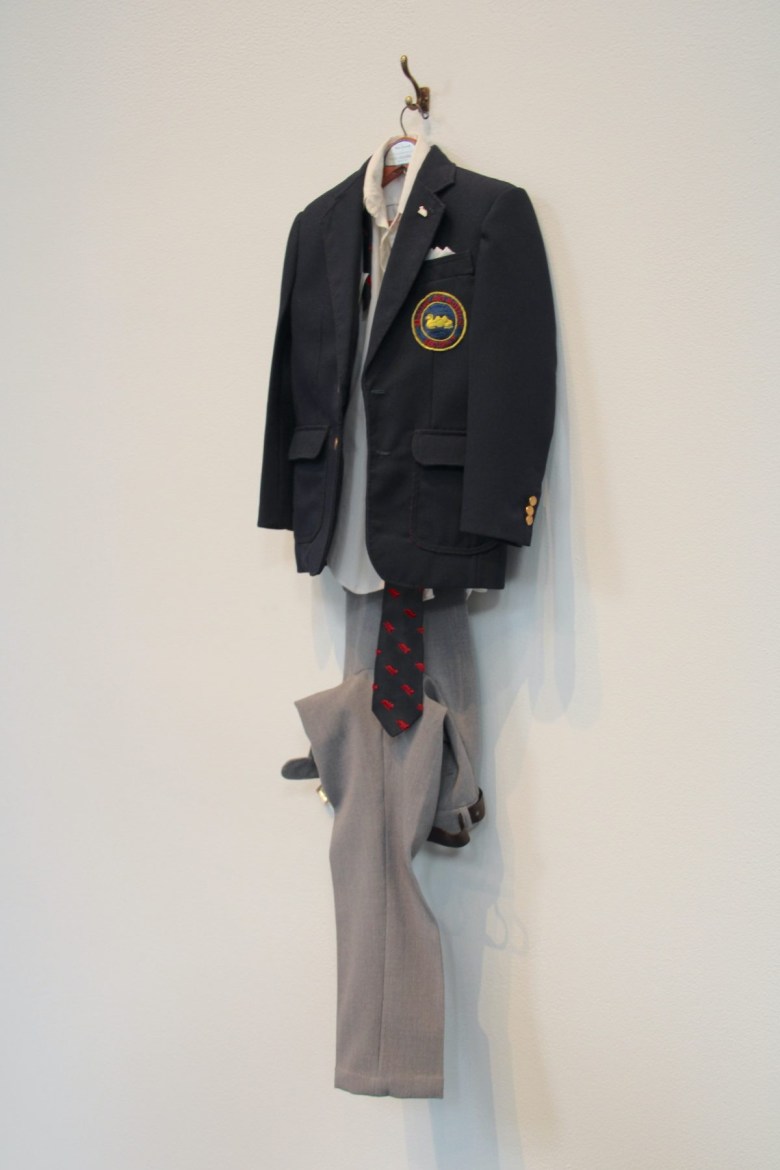

Charles LeDray’s sculpture toggles back and forth between the two poles of a deeply personal, talismanic intensity and a more open, iconic presentation, at times incorporating both qualities into the same piece. The first work viewers encounter upon entering his current exhibition, Shiner, at Peter Freeman, Inc. is a reconstruction of an earlier piece destroyed in a fire (“S.A.M.,” 2022–23). The roughly half-scale version of the uniform he wore as a guard at the Seattle Art Museum (SAM) is a resurrected memorial to both his youthful self and the work that initially brought him real attention in the art world. He eventually had his own solo show at SAM. Although we can’t see, visitors are told that the pockets of the gray pants contain a miniature pencil and scratch pad of drawings, and his museum work schedule. An enlarged version of one of the drawings hangs nearby.

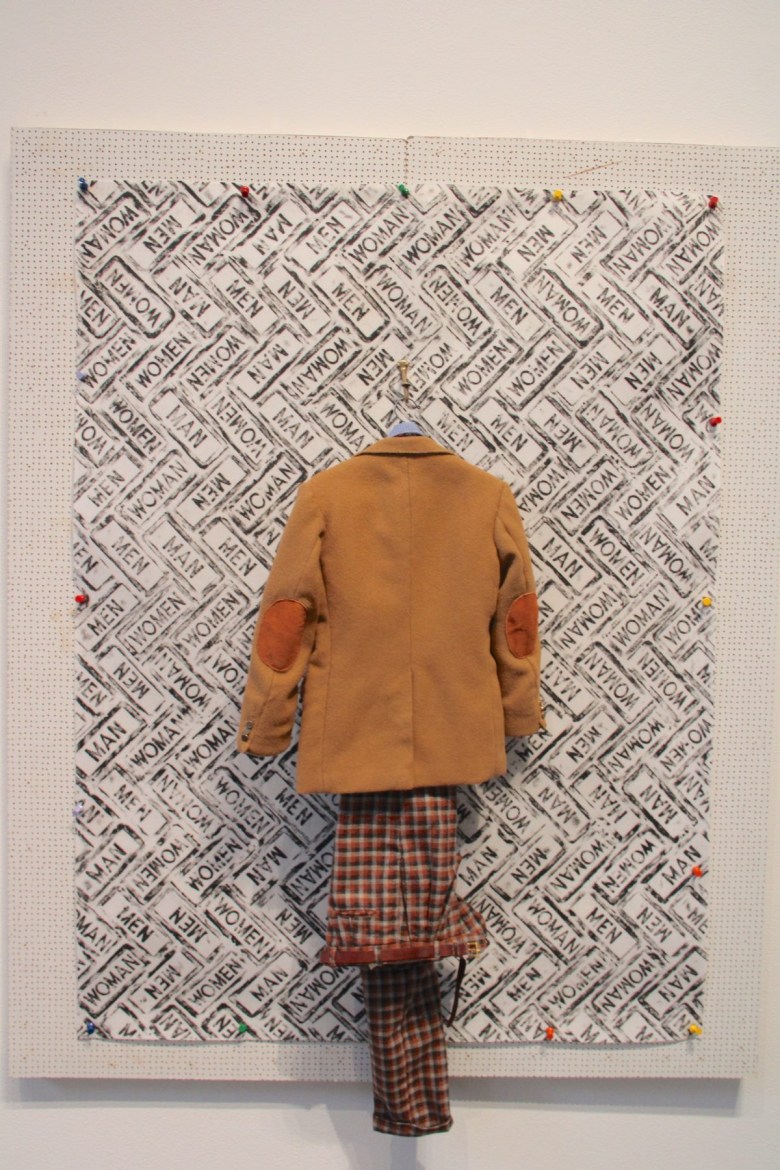

Other pieces in the show include a miniature shoe shine kit, along with associated paraphernalia, a reduced-scale hope chest overflowing with reproductions of his mother’s craft work, newspaper clippings, photos, ticket stubs, and the like, and another small suit on a hanger. Titled “Backward Suit” (2010–23), it pairs a camel hair sport jacket (with leather elbow patches) with a pair of plaid wool pants in a dramatically outdated style, fancy clothes for a working stiff in the 1940s or ’50s. All three pieces summon themes of pride, display, and intimacy in an overlooked or undervalued working class culture, a world in which LeDray presumably grew up and subsequently left far behind.

“Briefs” (2020–23) draws on another of LeDray’s longstanding interests, cigars. An edition of 27 miniature cigar boxes, each containing a different assortment of odds and ends, recalls a set of cigars and smoking equipment he made for a show at Jay Gorney gallery in 1996. Indeed, much of this show projects a feeling of nostalgia with an edge of melancholy, a Proustian search for lost time. How does the artist’s use of miniaturization relate to this feeling? It makes everything both close and distant; the toy-like scale gives everything a glow of childhood play and fantasy while pushing it far away.

The show’s most impressive pieces are “Revolution” and “Spool’n: How My Mother’s Embroidered Apron Unfolds in My Life” (both 2015–23) — the latter quoting the title of a famous Arshile Gorky painting in the Seattle Art Museum. Both are standing vitrines with glass on all sides and seven glass shelves. “Revolution” is filled with thousands of tiny hand-thrown terra cotta vessels in an encyclopedic variety of styles, while “Spool’n” contains thousands of thread spools, each decorated with a different pattern. The pots suggest a dollhouse fantasy gone into hyperdrive while the spools, with their connotations of domestic crafts, are decorated with folk-art-like patterns in bright childhood colors. They are both spectacular instances of LeDray’s insistence on handcraft, not so much in terms of the mark of the artist but as manifestations of time passing and the fruits of attention. Considered from this perspective, they seem almost like natural wonders.

Charles LeDray: Shiner continues at Peter Freeman, Inc. (140 Grand Street, Soho, Manhattan) through January 6. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.