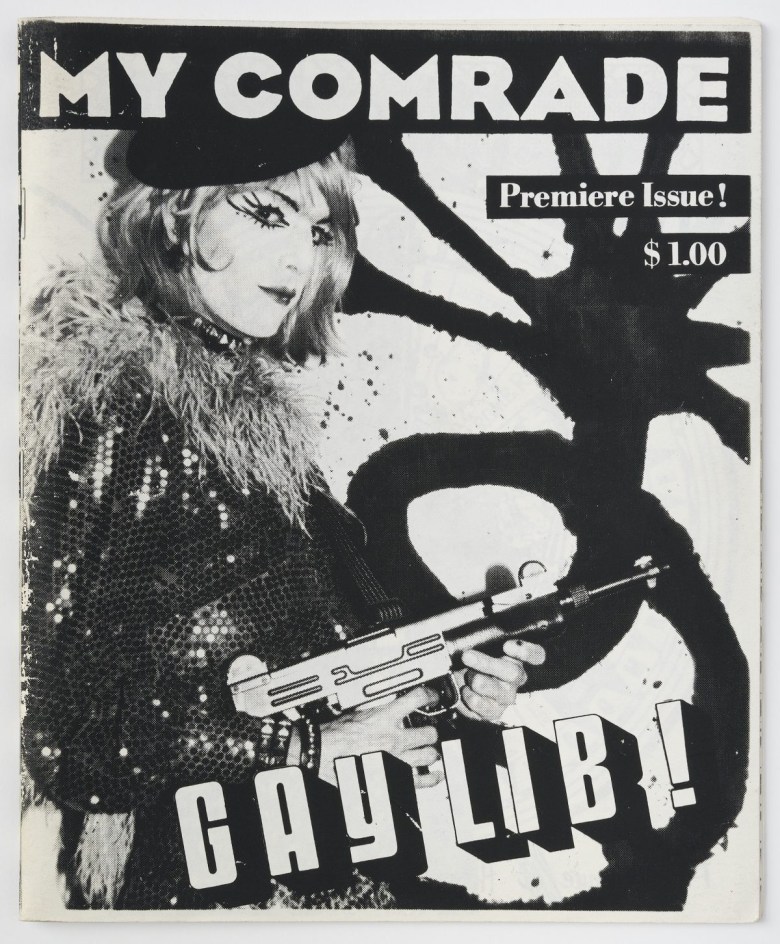

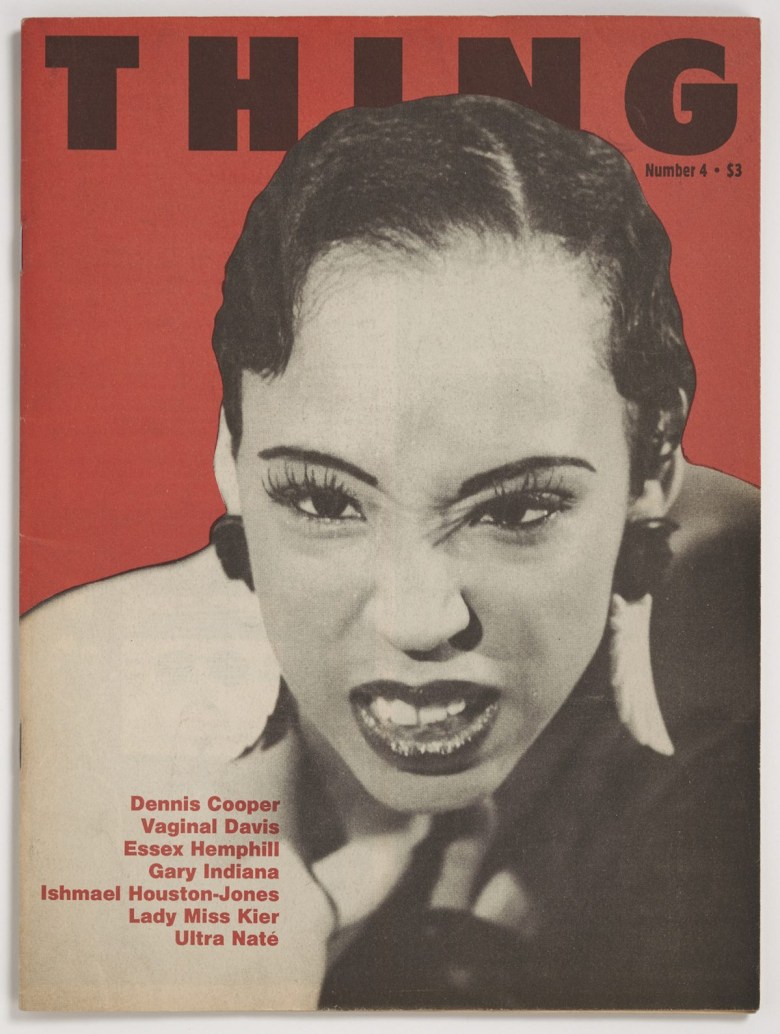

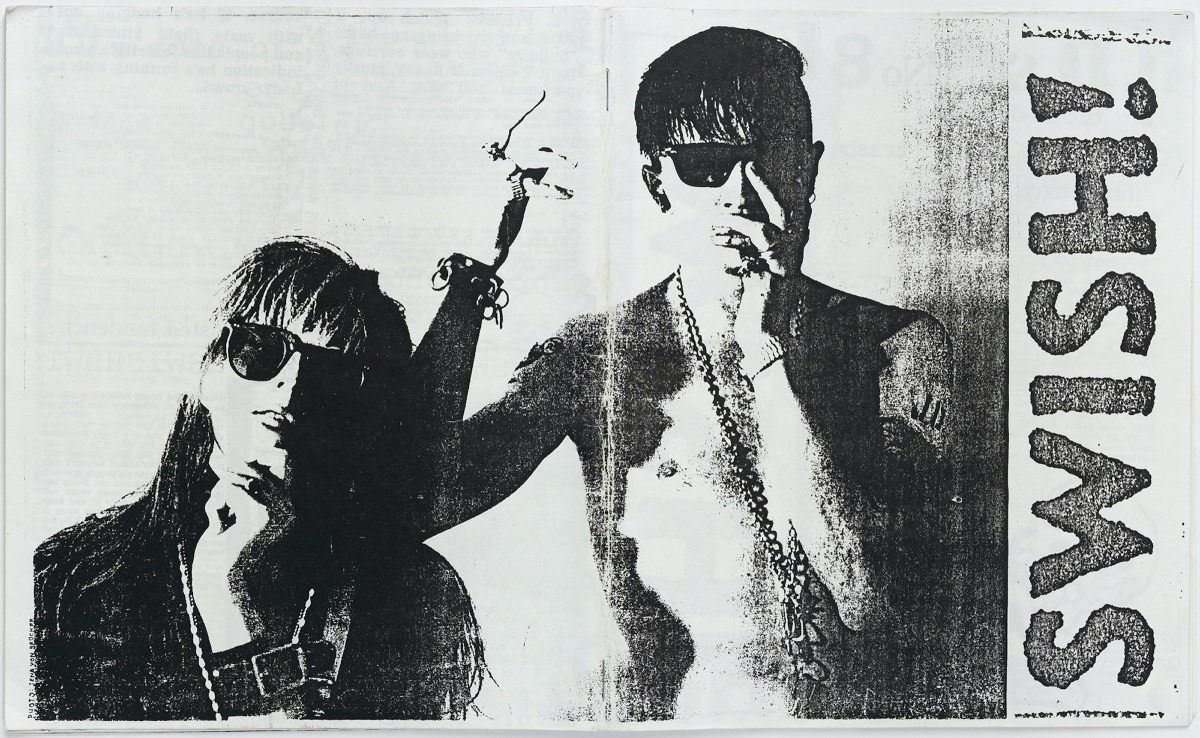

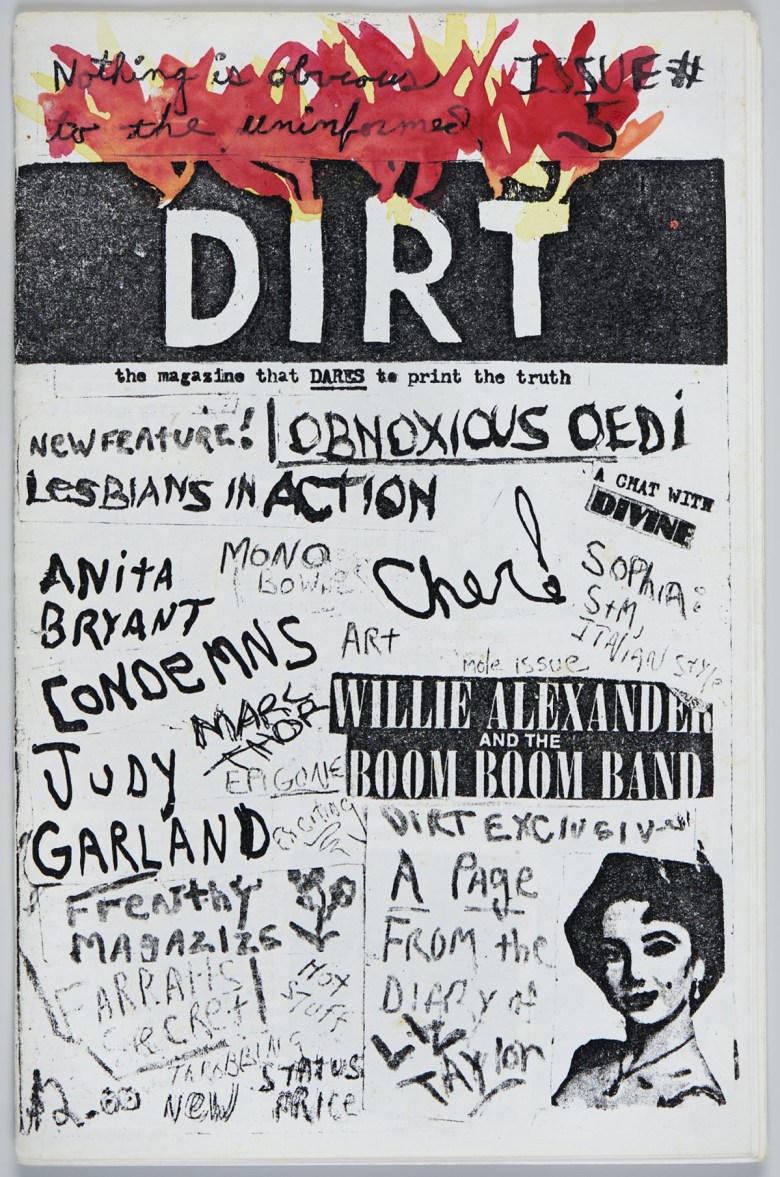

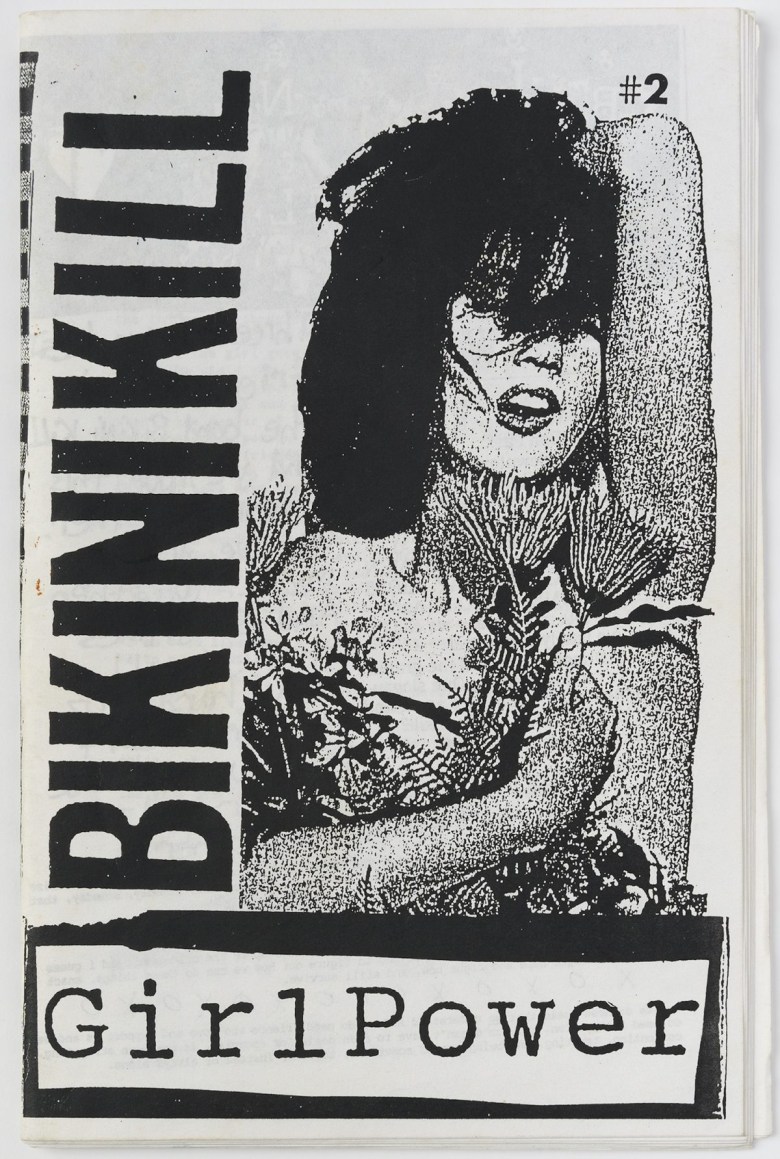

An homage to the countercultural movements of the late 20th century takes form in a forthcoming survey of fanzines, or self-published art magazines that gained popularity after the invention of the photocopy machine. Spanning five decades in roughly chronological order, Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines at the Brooklyn Museum opens November 17 with a nostalgic examination of the artist publications that served as a collective means of creative expression among underrepresented queer, feminist, punk, revolutionary, and experimental underground communities post-1970.

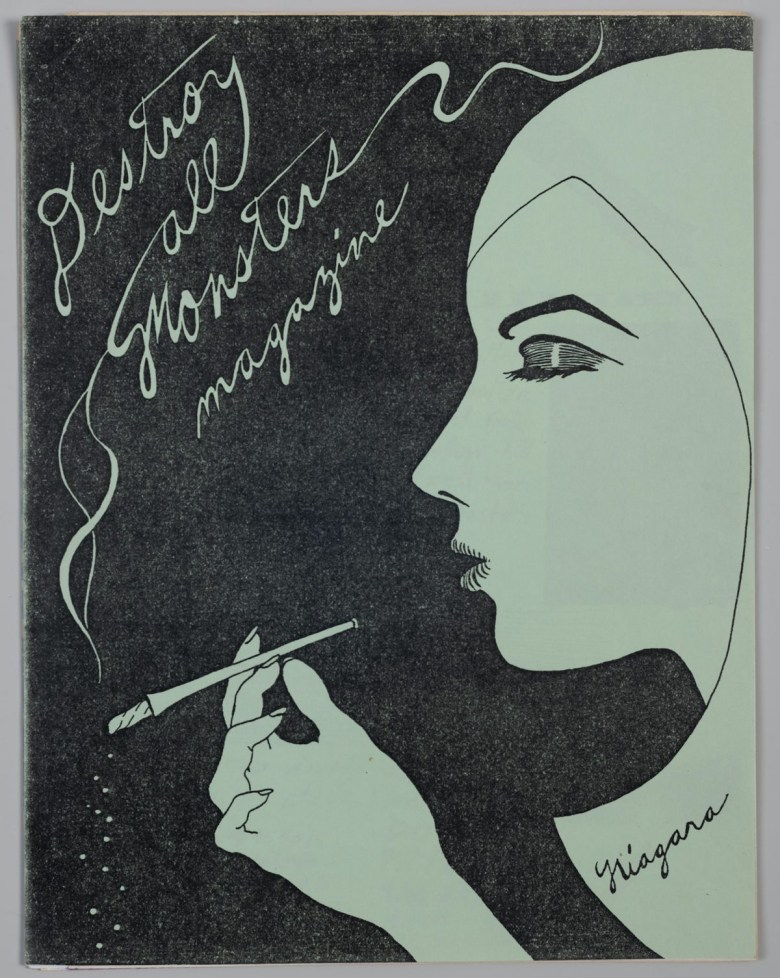

The multimedia show will feature more than 800 artist zines and associated works including original mock-ups and illustrations, films, paintings, performances, sculptures, and other works created by dozens of artists-zinemakers including David Wojnarowicz, Vaginal Davis, Johanna Fateman, Miranda July, Terence Koh and Kandis Williams.

“We chart a very specific kind of genealogy that hopefully helps situate for visitors their own understanding of what zines are today and show how they emerged at different points in North America over the past 50 years,” the exhibition’s co-curator Drew Sawyer told Hyperallergic. “In particular, we show how artists were always integral to that history.”

Copy Machine Manifestos will also explore how artist zines have helped catalyze sociopolitical change through their dissemination of historically marginalized stories, as in AIDS activist Cory Roberts-Auli’s Infected Faggot Perspectives or Lizania Cruz’s self-published works exploring immigration policy and the displacement of refugees.

Sawyer and co-curator Brandon W. Joseph explained that in 2019 they began sourcing zines from a variety of museums, galleries, private collections and libraries across North America and Europe to piece together a multimedia timeline over the next four years.

“We also spent a great deal of time contacting artists and visiting them in their homes and studios, sometimes literally helping them dig boxes out of storage that they had not opened in decades,” the curators told Hyperallergic. “Many artists were generous enough not only to share their time on Zoom, particularly during the months of pandemic lockdown, but also to dig through their own materials and send them to us for the exhibition.”

Copy Machine Manifestos will also observe how alongside late 20th-century avant-garde art movements, artists used zine culture both as an accessible medium to share work as well as to foster connections and experiences.

“It was artists who adopted — and in some cases participated — in fan culture, creating their own fan clubs around these sort of fictitious, ironic fanzine life performances,” Joseph explained.

Max Schumann, former Executive Director of art bookstore, distributor, and artist organization Printed Matter, noted that the term zine has evolved to encompass a much broader scope of self-published art books, but for the greater part of the ‘80s and ‘90s, zines were normally serial periodicals.

“Fans of underrepresented or unrepresented aspects of culture used simple office-duplicating technology — Mimeograph, later Xerox — in order to create a public forum for fellow fans,” he said.

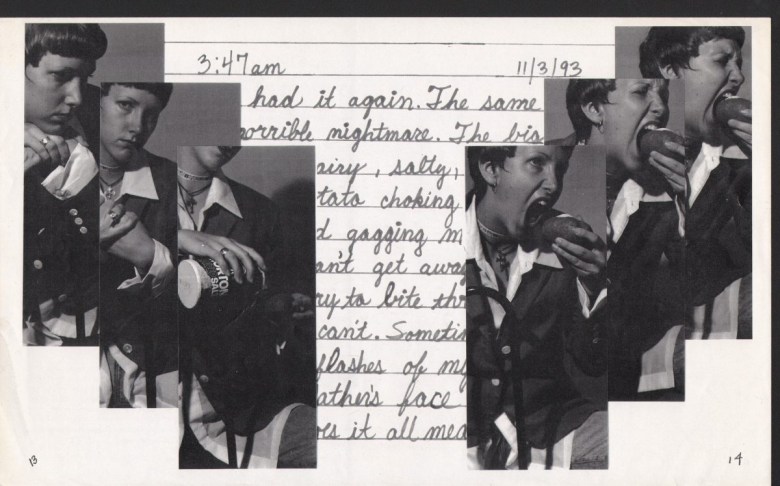

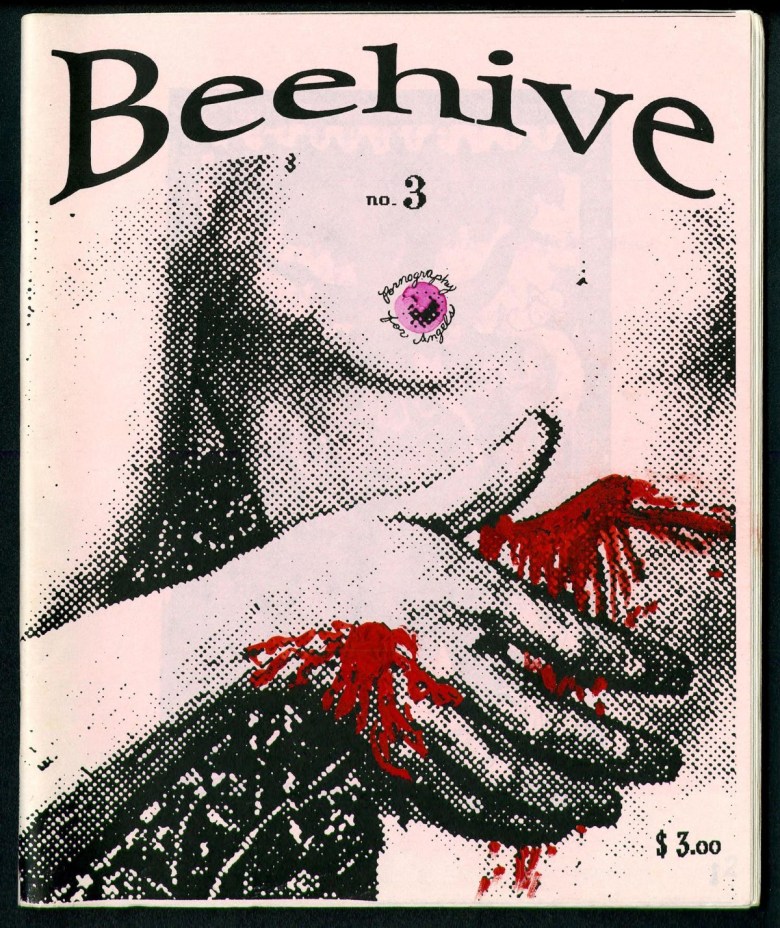

In the case of University of California Irvine art students Allyson Shaw and Laura Splan, from 1993 until 1996, Beehive was the feminist biomedical art zine that became their community forum. A multiple-page collage of original creative writing and artwork mixed with reappropriated text and visual imagery, Beehive was a hand-cut-and-pasted photocopy publication examining the intersection of feminist theory, body politics, medical history, and Riot Grrrl subculture produced in several print volumes and one early internet e-zine until 1996. In addition to Beehive, Splan and Shaw collaborated on other projects, such as an experimental poetry film that the pair produced in their university parking lot where they worked as parking attendants, which will be featured among the works in Copy Machine Manifestos.

Splan noted that in many ways, Beehive and her work with Shaw was a “through line” to her art practice today, which has expanded to 3D animation installations about biomedical politics, molecular models, and the boundaries of artificial intelligence.

“My work has always been about collage and appropriation and sociopolitical subtexts of images and language, as well as biomedical imagery,” Splan said.

As their publication expanded in readership beyond their Irvine campus to nearby communities. Splan recalled receiving fanmail from an inspired high school student nearby in the form of their own zine titled, Better Than Barbie — “a really quirky, funny zine about how real girls are better than Barbie because their toes can bend” and other underappreciated human abilities. The exchange of zines was a crucial element to zine communities, as readers continued to respond and build upon the work in their own means of expression.

As Joseph explained, a crucial element of zines is participation. In his own experience as a zine consumer and collector, he remembered corresponding with several artist zinemakers, such as Lynn Peril, the creator of Mystery Date, a ‘50s camp zine launched in San Francisco in 1994, and Pam Berry, who created DC zine Chick Factor with Gail O’Hara. Several of the issues he collected then, he still keeps in his office today.

“The zines obviously meant enough that I didn’t throw them away,” Joseph said.

Copy Machine Manifestos opens November 17 and runs until March 31, 2024. In conjunction with the exhibition, Printed Matter will be hosting a one-day zine fair on November 19 at the Brooklyn Museum. The event will feature more than 60 exhibitors, with a specific focus on self-publishing artists and collectives, archives, libraries, and rare book dealers.