LOS ANGELES — How do you capture something not meant to last? This question is central to the exhibition Queer Communion, a career-spanning survey of the work of the boundary-breaking Los Angeles-based performance artist Ron Athey, held at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (ICA LA).

Athey’s transgressive performances have, for the most part, existed on the cultural fringes, recognized by the high temples of art but held outside of them in alternative spaces and clubs. A self-taught artist, his work defies discrete categorization and commodification, blending high and low, the sacred and the profane. “Ron would take costumes from one piece to another. It’s confusing if you’re trying to pin down an object as meaning one thing,” exhibition curator Amelia Jones told me when we spoke over Zoom recently. “You see resonances in the way costumes circulate and recirculate. They’re living.” To capture the dynamic energy of Athey’s creative output, Jones avoided dry performance documentation, instead bringing together props, costumes, video clips, writings, photographs, and other ephemera into evocative tableaux, centering Athey’s life and work not in objects but within the supportive communities of friends, collaborators, and allies he has inhabited.

“The communities that changed me were communities that had to exist to survive, like the AIDS support system community,” Athey said during an online art talk organized by the ICA LA this past June. (Athey has been HIV positive since 1985.) “The early homeless punk scene was also about survival, about being parentless, about being queer and kicked out … These communities are about survival and then they get deeper than blood.”

Eschewing a strict chronological format, the exhibition is organized thematically, loosely divided into sections like Religion/Family, Music/Clubs, and Art/Performance/Politics. Explicative wall labels are brief, and the hefty catalogue edited by Jones and Andy Campbell is packed with texts — both by and about Athey — serving as another facet to the show, providing deeper context. Less academic tome than glorified zine (in the best sense), it offers intimate, insider accounts, capturing Athey’s generosity, intellectual curiosity, and humor.

Queer Communion opens with “Joyce” (2002), a four-channel performance documentation named after his mother, who was institutionalized with schizophrenia for much of her life. Depicting scenes of self-mutilation, vaginal fisting, and Athey undergoing a kind of homemade EEG via needles inserted into his head, the work conjures the women who featured prominently in his childhood, including both his mother and aunt, as well as Miss Velma, a charismatic preacher whose flamboyant wardrobe and theatrical services left an outsized impression on him. “Miss Velma was my mother as much as my mother was,” he told me over coffee in his apartment on the border of Silver Lake.

Athey was raised in Pomona, on the eastern edge of Los Angeles County, by his grandmother, who trained him to be a Pentecostal preacher. His religious upbringing would have a profound influence on his work, which is imbued with allusions to spiritual fervor, ritual, and Catholic symbolism. This thread is woven throughout the show, from a foot washing set with a hair towel alluding to Mary Magdalene washing the feet of Jesus, to Catherine Opie’s photo of Athey as the arrow-pierced Saint Sebastian.

As a teen, Athey channeled the passion he had for religion towards LA’s underground punk scene. “I feel like that’s the fanatical side of me,” he told me. “I dove into punk rock like it was a church.” He formed the experimental industrial group Premature Ejaculation (PE) with his then boyfriend Rozz Williams, of goth/deathrock band Christian Death. Although PE would only play two shows, they marked the beginnings of the extreme body-based rituals that Athey would become known for. “The early punk scene was a lot more cabaret than is documented,” he said at the ICA talk, noting how bills would blend genres, featuring performance artist Johanna Went alongside punk bands like Black Flag and Fat & Fucked Up. “The art door opened for me via music. When I saw the way Johanna twisted images and used motion, something clicked inside of me.”

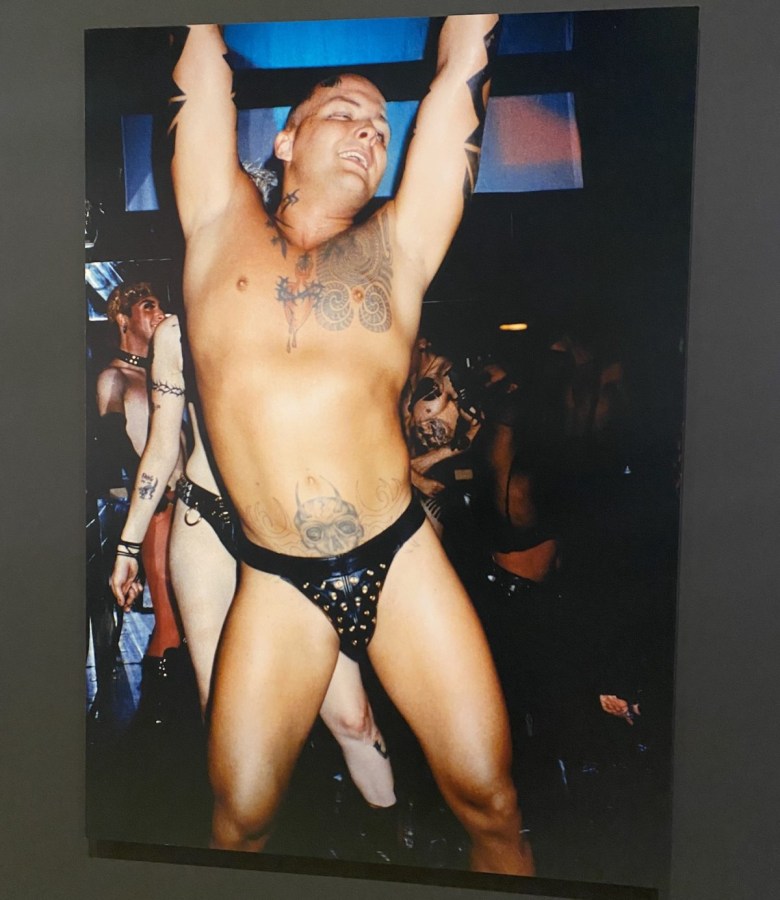

The “Music” section also documents his involvement a decade later, in the early ’90s, with Club Fuck!, an inclusive queer party that provided celebratory liberation for a diverse tattooed and pierced community that existed outside of both the establishment straight and gay worlds.

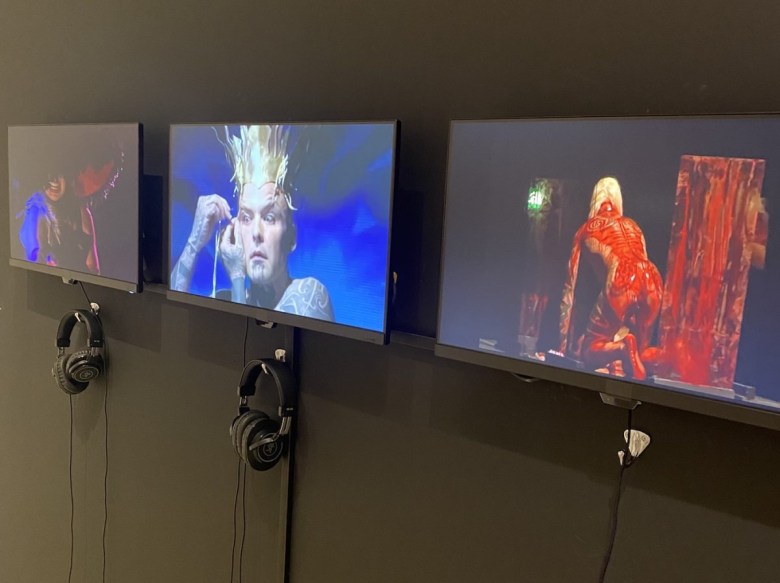

Seminal performances are represented through video excerpts, props, photos, and texts. These include “Judas Cradle” (2005), named for the pyramid-shaped medieval torture device which Athey perches upon, transforming it into a vehicle of queer eroticism, and “Solar Anus” (1999), a reinterpretation of Georges Bataille’s 1931 surrealist text in which Athey inserts a stiletto-heel dildo into his anus and dons a golden crown held in place with facial piercings.

Athey bristles at the accusation that he was trying to shock by engaging with what some might consider taboo and abject. “Back then people used the stupid term ‘shock value’ all the time for everything, and tried to dismiss things,” he told me. “Everyone thought if you weren’t being mainstream you were just taking the piss, right? Well, no one cares about your boring ass, even enough to resist against. We were just having fun.”

Jones, the show’s curator, echoes him, saying that shock “was not close to his motivation. When you live in certain circumstances, or in a state or precarity, these things aren’t shocking.”

Despite his disinterest in shocking his audiences, controversy found Athey in March 1994 when he staged “Four Scenes in a Harsh Life” at Patrick’s Cabaret in Minneapolis. This was the middle portion of what he calls his “torture trilogy,” which addressed the AIDS crisis through masochistic ritual and religious imagery, “aligning HIV with plague in biblical terms,” he said of he trilogy’s first part, “Martyrs and Saints.”

“Everybody was dying then,” Athey told me. “It seemed like the end of my world, which is more intense than imagining the end of the whole world in a way. It’s more personal. There are those times when there’s no reason to mask things and present it aesthetically. It’s just like you’re bleeding out, crying yourself to death.”

In one scene, Athey made incisions in the back of one of his frequent collaborators, Divinity Fudge, dabbing the wounds with paper towels which were then hoisted into the air above the audience. He was dragged into the culture wars when a sensational story appeared in the Minneapolis Star Tribune and spread like wildfire, driven by AIDS panic (even though Fudge was HIV negative) and controversy over public funds being used for the project, which amounted to $150 from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) via the Walker Art Center. Jesse Helms denounced Athey on the Senate floor and proposed an amendment to prevent the NEA from funding art that featured mutilation or bloodletting. In Queer Communion, Helms’s speech is shown on an almost comically small television set, so as not to let the controversy overshadow the work. The incident led to what Athey calls a 10-year cultural blacklist in the US. The cruel irony is that the fiercely independent artist has never applied for public funds to finance his work.

“[To] be attacked, to smell the attack coming, was unbelievable because I wasn’t participating in this system,” he told the Walker in 2015.

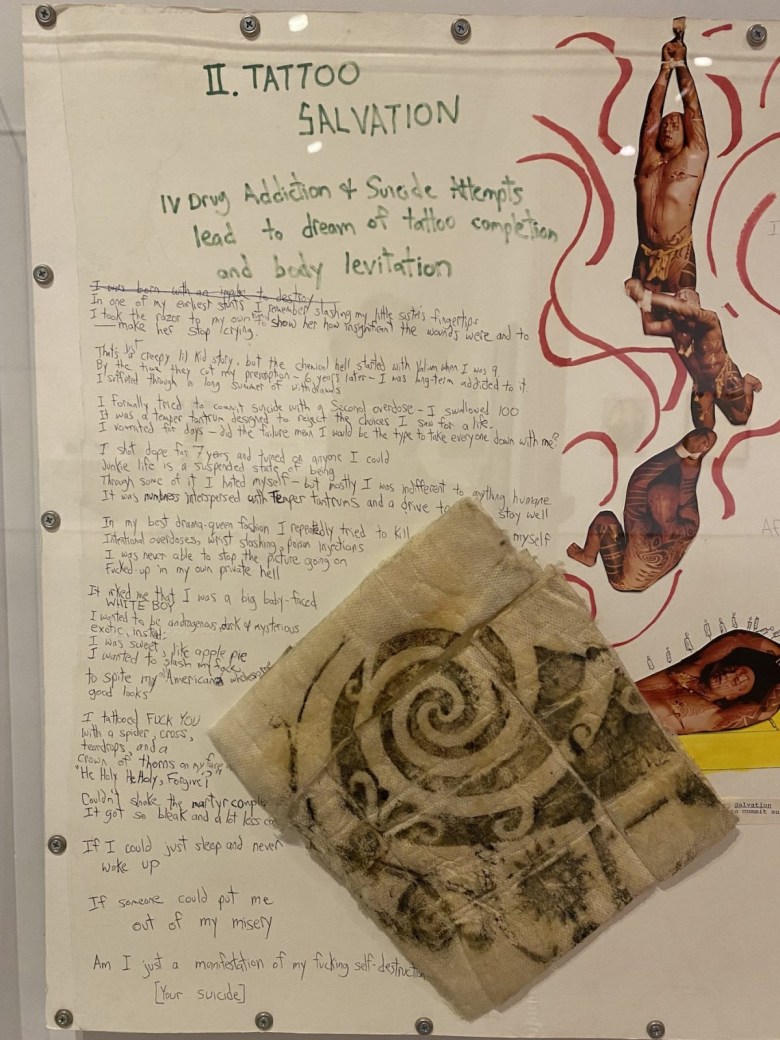

In addition to video and photos, “Four Scenes” is represented in Queer Communion by Athey’s storyboards, the only work in the show from the collection of a museum, namely the Walker. Composed of collaged images, drawings, and texts, the storyboards illuminate the nexus of references and meanings behind the work: black-clad leather daddies, Pentecostal preacher Aimee Semple McPherson, autobiographical accounts of his drug addiction and suicide attempts.

Jones was aware that there was no way to approximate an actual performance in the exhibition space, even through film, but fortunately, REDCAT presented “Acephalous Monster,” one of Athey’s most recent works, to coincide with the show at the end of August. Taking its title from Acéphale — Bataille’s anti-fascist secret society based around the archetype of the headless man — the performance draws on a heterogeneous mix of sources: the surrealism of Brion Gysin; the beheading of Louis XVI; the Greek myth of Pasiphae, mother of the minotaur who hid inside a wooden cow to mate with a bull. Opera Povera provides musical accompaniment, and vocalist and artist Carmina Escobar’s vocals recall glossolalia, or Pentecostal speaking in tongues.

The five scenes range from a very stoic Athey standing at a lectern reading Bataille’s text on Nietzche and the horse of Turin, to the artist as disemboweled minotaur writhing in a pool of UV fluid wearing a bright red bull mask, his heavily tattooed, nude body glowing blue. “It’s like a popped-out blacklight image. That’s the oldest cheapest trick since the ’70s,” Athey told me, “but all of sudden, you’re in in a different reality.” In the last scene, Athey appears as a cephalophore — a decapitated saint who carries their own head — while a performer cuts his chest, pressing lengths of cloth onto the wounds and hanging them up.

Queer Communion is Athey’s first major US museum show, and it succeeds in offering glimpses of a living practice that has not waned. Despite the institutional recognition that he is receiving, Athey has no interest in compromising his vision for greater financial or critical support.

“I firmly believe you don’t have to live in the big picture. That’s what’s wrong with this moment. Everyone wants to be president. I don’t get it…” he said during the ICA talk. “I firmly believe in making a strong, local movement. And not waiting for the system.”

Queer Communion: Ron Athey continues at the ICA LA (1717 East 7th Street, Downtown, Los Angeles) through September 5.