LOS ANGELES — Catherine Opie’s work is not easy to encapsulate. I could tell you that the queer, Los Angeles-based photographer’s portraits and landscapes, presented in a new monograph by Phaidon, explore the concepts of community, identity, and judgment. But that would be defining her work, and the whole point, as Opie says, is to allow viewers to bring what they will to each of her photographs — to encourage people to navigate rather than conclude.

“I’m less into leaving a legacy and more interested in leaving a map of my mind,” Opie said during a phone interview.

In the book, Opie’s mind is mapped onto the categories of “People,” “Places,” and “Politics.” The thematic organization works well with her freeform interests and habit of revisiting subjects and sitters across the years, including moving portraits of friend and artist Pig Pen and a child-turned-young-adult named Jesse. Introduced by art historian Elizabeth A. T. Smith and concluded with a thoughtful conversation between Opie and curator and writer Charlotte Cotton, the monograph spans 30 years of Opie’s explorations into deeply personal territory and across the ever-shifting boundaries of identity.

For those who are familiar with Opie’s work, it’s likely that what first come to mind are the seminal 1990s portraits of herself and friends from the queer leather community, made as countercries against the vitriol being spewed at the queer community during the height of the AIDS epidemic. Showing “Self-Portrait/Pervert” at the 1995 Whitney Biennial — which depicts Opie shirtless, wearing a leather mask and chaps, with piercings through her arms and “Pervert” cut into her chest in stylized letters — was both an early landmark of her career and a powerful, vulnerable act. But Opie’s goal for the book, she said, is to introduce audiences to “the larger breadth of my practice.” Her portraits have been followed by landscape series and close examinations of other communities as well as a 20-year teaching career at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where she was recently appointed chair of the UCLA Department of Art. The self-portraits were an essential starting point for her, but Opie has much more to share.

Opie aims to “understand the world in a more humanistic way,” asking big questions in specific detail. “I’m looking for a broader understanding of how we actually get to be a better world, examining the world to ask those harder questions — like hopping in an RV during the pandemic and making images of monuments throughout America in relationship to white supremacy and the history of slavery,” Opie said, referring to her photos from a 2020 project that include monumental landscapes and graffitied monuments of Confederate generals.

Most recently, she has been working on a series on the “walls, windows, and blood” of Vatican City, excavating the relationship between the Catholic Church’s ostensibly humane doctrine and its acts of violence over the years. “I don’t want to necessarily take on the Catholic Church,” she said, “but when you get a residency in Rome and Vatican City is such a part of that, then you automatically drift down there. It was just what I wanted to actually have a conversation with.”

The key to Opie’s work may be that she engages in photography as a conversation. She is willing to look closely at many aspects of the world and examine the truths that emerge, bearing witness rather than asserting a thesis through her images. Opie’s portraits acknowledge the fact that identity is mixed and mutable: from high school football players performing toughness and vulnerability on the field, to lesbian couples at home, to people growing into new roles as they age. Her photographs are never snarky or othering but insist on the inherent dignity of her subjects — itself a rare act of sincerity. To Opie, it’s about “understanding what it is to be inclusive.” She does not force or suggest specific emotions in her photos, instead choosing to visualize a moment, step back, and let the audience read into it what they may. There is a resulting starkness about her work, and an intimacy, too, in that level of trust.

Opie’s mostly untitled images of Elizabeth Taylor’s closet, 700 Nimes Road, offer no obvious connection to the famous actor apart from the titular address. Instead, Opie allows viewers to glimpse aspects of a highly recognizable person through the lens of her possessions: the sumptuous colors and textures of her clothing, her famed jewels both in and out of focus. The fragmentary portraits raise more questions than they answer about the elusive Liz. Included in both “People” and “Places,” the photos also defy categorical boundaries, revealing Opie’s characteristic interest in navigation over definition.

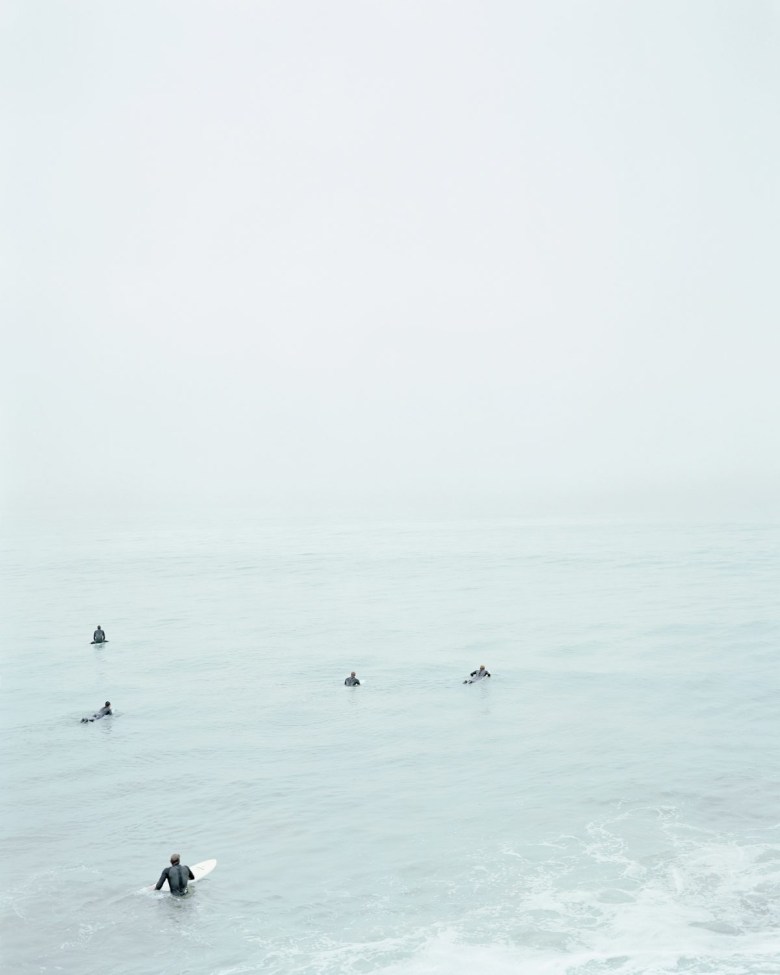

In her landscapes too, Opie is not interested in leaving a trail to follow; she frequently keeps photos untitled and locations vague. “I’m not interested in having my steps traced that way” by providing directions, she says in the book. Instead, she hands over the map.

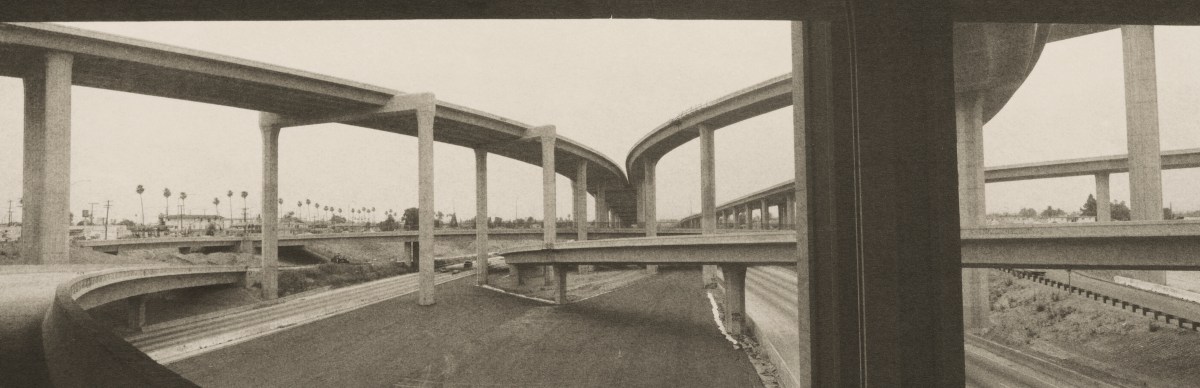

As Opie’s landscapes are mostly devoid of people, focus, texture, and shape become the paramount waymarks. The images range from blurred to crisp, from choppy and still water to harsh cement, from the angular geometry of a room to the barren curves of freeways. Though varied in subject and approach, the landscapes are united by similar sensations of stillness, distance, and unknowability.

Having lived in Los Angeles since 2001, Opie has visualized the city’s unconquerable complexity in many ways. Opie’s is not the Hollywood dreamscape but the everyday LA of mini-malls and freeways, which evoke its personality without a person in sight. “Mini-malls are a fascinating way to think about looking at the city,” Opie said on our call. “You understand a city in terms of its neighborhoods and its communities, and in relationship to immigration, all through that façade.”

LA is often said to be a place obsessed with surfaces, but Opie is interested in the realities of its façades, not the filtered versions. Whether photographing faces or buildings, “I try to photograph exactly how it’s lit and how it is, she explained. “I’m really interested in just the way that things are presented and trying to be authentic within that.”

Through her work, Opie contributes to the authentic community she has found in LA. “I’m fascinated by this city, and I think it’s one of the great cultural cities,” she said. “I think that LA is phenomenal in terms of how many amazing schools there are to actually study art. It always has been a community of young artists, as well as [having] prominent artists [as] teachers here. That notion of community and mentorship has always been really attractive to me.” The notion of community permeates Opie’s work, uniting her disparate subjects into a larger project. As with LA itself, focusing on the individual people and elements that make up its communities allows a greater picture to emerge.

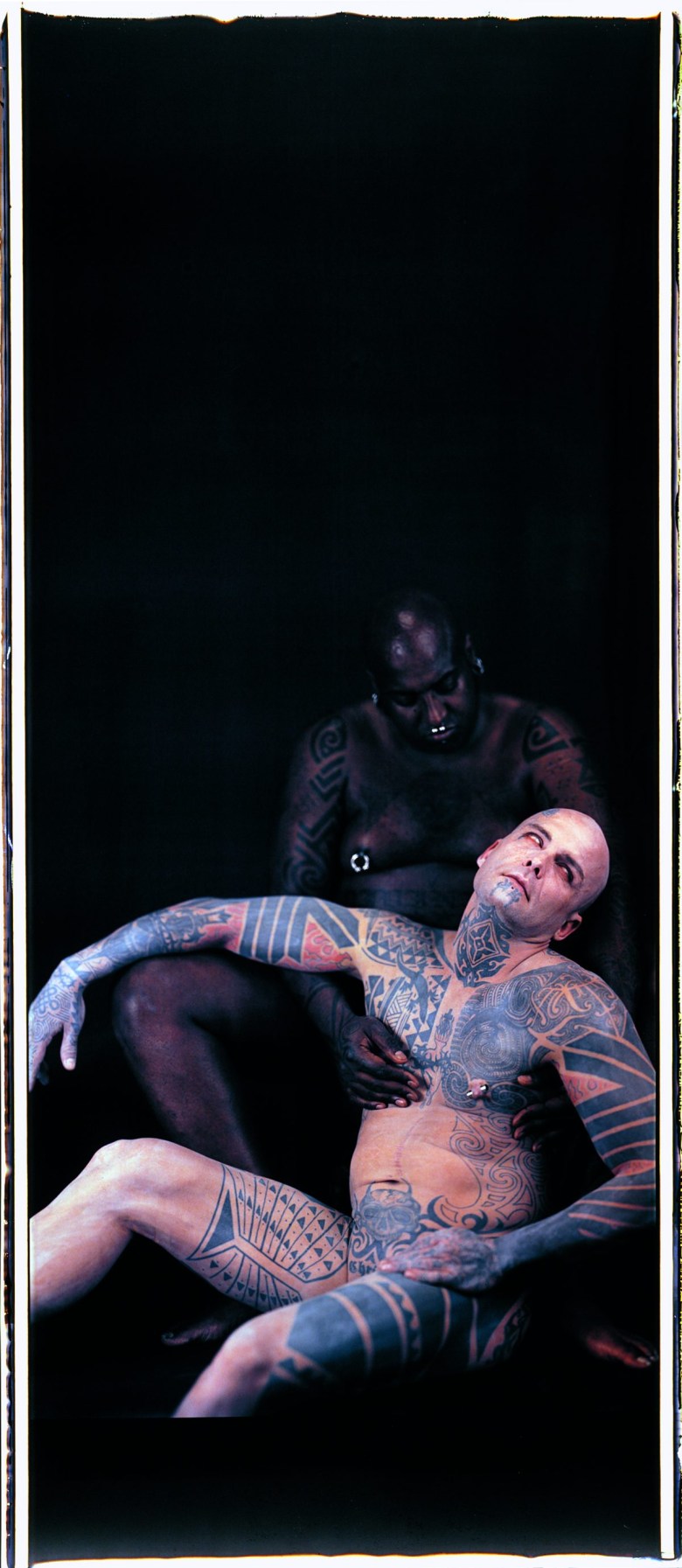

Despite having its own chapter, politics is necessarily woven throughout the book. Opie’s chief political device is to subvert (or ‘pervert’) tradition by depicting her subjects in the formal iconography of art history to challenge conventional ideas about who and what gets represented. “Ron Athey/The Sick Man” (2000) is cradled like a pietà, while “Kate & Laura” (2012) resemble a queered Annunciation scene; “Thelma & Duro” (2017) are posed like a Dutch Golden Age marriage portrait. Hans Holbein’s influence is evident in Opie’s self-portraits and images of queer friends, which are imbued with the same gravitas a 16th-century court painter would provide. In Opie’s other political work, she disarms with the unexpected: a TV reporter caught in a blink, or a lone rainbow kite tugged by a breeze.

Opie photographs people, places, and politics without reducing them to stereotypes or urging a simplistic narrative onto a series. In the context of the supposed fracturing of American identity and communication, Opie’s approach is refreshing, even radical — rather than trying to explain how and why we are fractured, she focuses on what might blur our boundaries instead. “All of it in the end is hopefully getting people to just stop and think about the greater aspects of how we create … a society together, and what it means to be accepting,” Opie said. Then she laughed. “You know, all of that hokey stuff.”

“I am enough of a realist to know that in making political work, I can’t necessarily make political change in a grand way. But I can hopefully add to a dialogue,” Opie said. Through her work, Opie challenges the body politic to meet the body complex, to wrestle with its own contradictions and undefinition, and to contemplate what it might mean to approach our own bodies, façades, and structures with open eyes and open minds.

Catherine Opie is now out from Phaidon and is available on Bookshop.