CHICAGO — Though relatively unknown in the United States, the Spanish-Mexican painter Remedios Varo is beloved in her adopted Mexico, where she moved as a refugee of World War II. The artist’s enigmatic oeuvre is deceptively compact, but spend any time in front of these self-contained scenes — often housed in incredible architectural spaces, like the celestial tower in “Embroidering the Earth’s Mantle” — and you’ll find they contain universes.

Though she is often called a Surrealist, and while her figures’ heart-shaped faces and spindly forms do evoke those of her friend and fellow European expatriate Leonora Carrington, the internal logic of Varo’s paintings — as is so brilliantly manifest in the one-wheeled, wind-propelled vehicle in “Vagabond” — make that label an uncomfortable fit. Classically trained as a painter at the prestigious Academia de San Fernando in Madrid and the daughter of an engineer, Varo is more meticulous in her process than the other artists of the movement with whom she is often compared.

To help me make sense of this multifaceted artist, I joined Caitlin Haskell, the Art Institute of Chicago’s curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, for a tour of the exhibition Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, currently on view at the Art Institute. With works spanning from 1955 to 1963, the years during which the artist worked in her mature style, the show features more than 20 paintings, as well as studies, notes, and other ephemera from Varo’s archival material. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Hyperallergic: Tell me about the show — the first solo Remedios Varo exhibition in the United States since 2000.

Caitlin Haskell: It’s a small show in some ways, only 3,000 square feet. We have about 60 works, with more than half being shown in the US for the first time. But the thing that’s really special about this exhibition is that almost every visitor who comes into the show is seeing Varo in person for the first time.

H: That’s certainly true. I heard one visitor excitedly proclaim, “I’ve never seen art like this!” which is the reaction I had when I first encountered Varo a few years ago.

CH: The show is not intended to show a trajectory. What [guest co-curator] Tere Arcq and I were interested in was conceiving Varo’s practices as having two sources of mystery, one of those being the literary and thematic sources that she pulls from and the other being the work’s materiality.

So in [opening works] “Caravan” and “Discovery” immediately you see areas of figuration, areas of storytelling and narration. Here’s a musician — music plays a big part in Varo’s work — within architecture that does not make rational sense. But then there are these incredible passages of material abstraction, often using decalcomania—

H: From Max Ernst?

CH: Yes, the same technique. Also, she uses other Ernstian processes like grattage and soufflage.

H: Clearly, Varo’s work is complex in both technique and content. In order to understand an artist, I always like to focus on material and process as an entry point. How did Varo make her works?

CH: The majority of the paintings that you’re going to see in the exhibition are made on masonite. She’ll put down several coats of gesso, sand it down, and then often rub something over it to create textures. One of the interesting discoveries of the exhibition was that it seems as though she was using quartz crystals to create marks. If you look at the photograph that we have at the start of the exhibition you can see there’s a crystal on her easel.

Once the gesso is down, she then makes a full-scale cartoon, a one-to-one drawing on transfer paper. And that will go onto the gessoed masonite, like a carbon paper, transferring over those lines. And then she starts painting.

So there’s a very tight, controlled aspect of painting and then there are these automatic techniques. There are aspects of sight, but there’s also an incredible amount of touch. And then after all of that — the combination of the figurative and the abstract together — then she will go in and score the surface.

H: It’s incredible to think that she made all of this work in such a short period of time, from 1955 until her death in 1963 at the age of 54.

CH: Some of that is a factor of her own biography. When she moves to Mexico City in 1941, she’s with [poet] Benjamin Péret. At that point in time, she’s taking a lot of commissions to support herself. It’s only once she meets Walter Gruen, who was her partner at the end of her life, that she has dedicated studio space and dedicated time to make work. All of a sudden, she is incredibly prolific. And a lot of those ideas have been forming for quite some time.

H: It’s just amazing to hear these narratives perpetuated about how the man in a partnership goes out and makes money, while the woman is a dilettante at home making art. It’s so false. There are so many examples of women artists having to be the breadwinners, having to sustain their practice in addition to their husband’s or partner’s practice.

CH: Certainly. It’s all too common.

H: What delights me most about Varo is her inventiveness when it comes to vehicles. I see all sorts of modes of transport in this show — boats made from overcoats, houses on bicycle wheels, and on and on.

CH: In Varo’s work there is often a sense of geographic travel, whether that’s by land or by sea, but also a sense of traveling down material pathways that no one has ever looked at before. There’s a type of discovery that can take place in an artist’s studio, in a parallel way [to the discoveries found on a physical journey].

“Vagabundo” is a case where you see some of these incredible articles of clothing that also function as personal vehicles or habitats in which you can travel the world. It’s such a magical work. All of these lines here on the pulleys, all of those are sgraffito incised into the surface of the masonite.

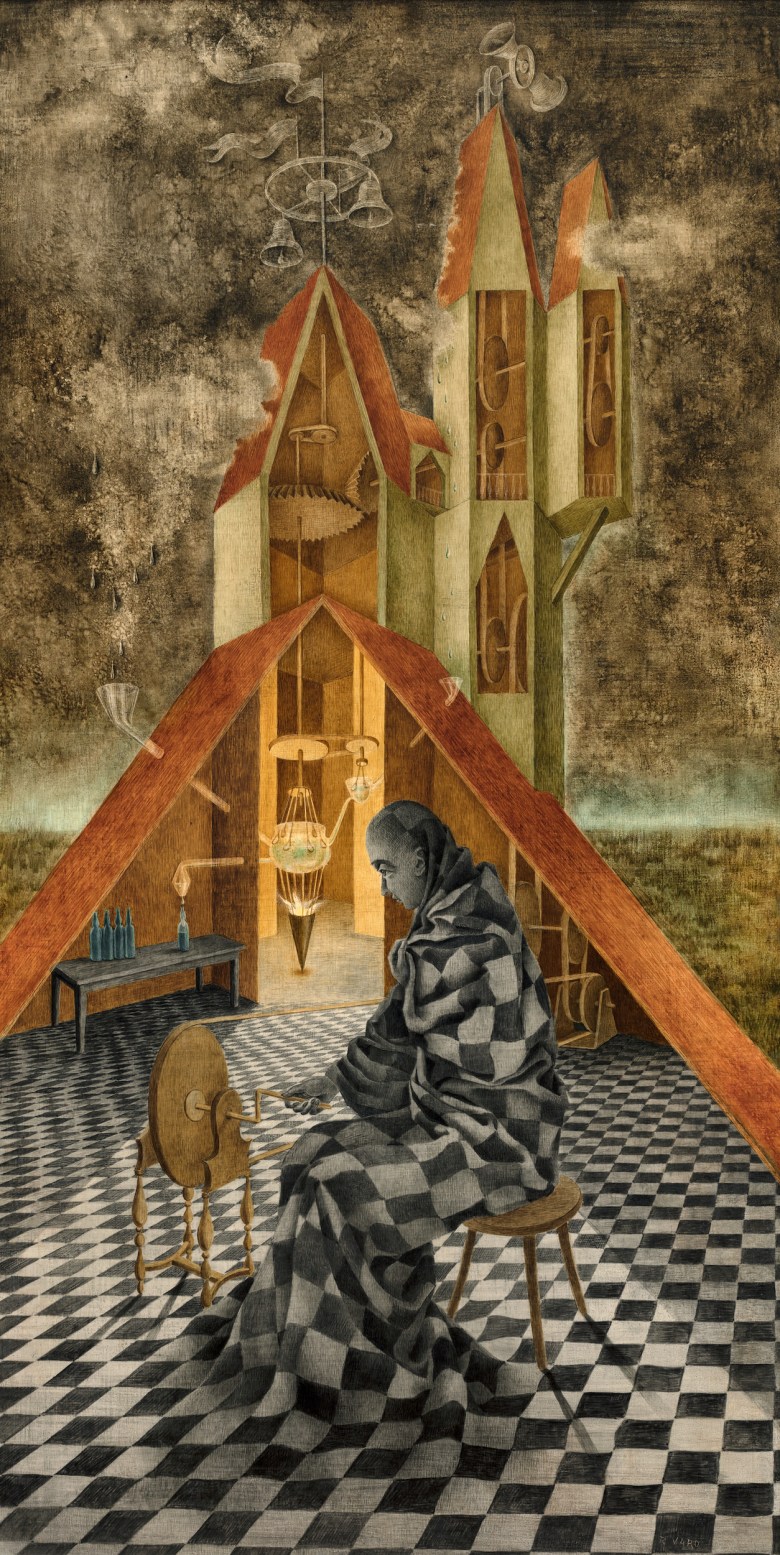

Remedios Varo, “Ciencia inútil, o El alquimista” (Useless Science, or The Alchemist) (1955); Museo de Arte Moderno (INBAL/Secretaría de Cultura © 2023 Remedios Varo, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid, photo by Rodrigo Chapa)

H: Ropes and pulleys are everywhere in her work! And so finely rendered. It’s charming.

CH: It entices you to look so closely. It goes back to her biography: Her father was a hydraulic engineer, from whom she learned how to make very precise drawings. She has this wonderful ability to be so specific in those drawings, but also bring you into a realm of imagination.

H: I think this is a really great opportunity to talk about whether or not Varo is a capital-S Surrealist. To me, her work feels utterly unique, different from any of her contemporaries.

CH: You’re right, it is utterly unique. But I think Surrealism is helpful as a framework because Varo is so new to many of [our visitors]. These works are from ’55 to ’63, so her engagement with [Surrealism founder André] Breton was decades before these works were made. And she even says in an interview from ’57, “I don’t belong to any group.” But again, on the other hand, her social circle in Mexico is Leonora Carrington, Kati Horna; [Frida] Kahlo was an acquaintance, and people who — if you’re going to put them into any of the larger buckets of 20th-century art — are most associated with Surrealism.

H: And of course, many of her automatic techniques are very closely tied with the movement.

CH: One of the very special things that you’ll see in the catalogue is that we worked with a paper conservator and a paintings conservator to do what we call a “taxonomy of techniques.” So there are 23 different techniques that each have their own entry, which Varo was using in a collage-like way in creating her extremely captivating surfaces.

H: Somehow the catalogue’s taxonomy — which defines techniques like those we mentioned early, decalcomania and soufflage, for example — helped me make sense of how Varo came to make such complex images, but paradoxically, it also preserves the magic each contains. Knowing how she made her work doesn’t solve their mystery. Her work is greater than the sum of its parts.

CH: Precisely. I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Remedios Varo: Science Fictions continues at the Art Institute of Chicago (111 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois) through November 27. The exhibition was curated by Caitlin Haskell and Tere Arcq.