Editor’s note: The following interview contains descriptions of animal death and cruelty.

LOS ANGELES — For the past half century, Kim Jones has been making art that interrogates the brutality of humankind. Two pivotal life events are frequently invoked as source material for the artist: his childhood battle with Perthes, a polio-like disease that confined him to a wheelchair and leg brace from ages seven to 10, and his service as a US Marine in the Vietnam War from 1966 to 1969. Traces of these events appear throughout his oeuvre. His childhood confinement allowed him to explore his early interest in art: It was at this time that he started a series of drawings resembling aerial views of battle plans, often referred to as “war drawings”; his tour of duty surfaces most viscerally in “Rat Piece” (1976), an infamous performance in which Jones burned rats alive. The act, which prompted outrage and landed him in court, sought to replicate soldiers’ retaliation against invading rats in their camps, but it conjures the ghostly presence of rats in war zones past. (For instance, rats weave in and out of the earth in Otto Dix’s War etchings like messengers from the underworld.)

To connect his art solely to these moments, however, is to neglect his complex entanglement of life experience and art historical references — glimmers of Medieval and Renaissance bestiaries and grotesques, the Baroque elegance of his drawings, the influence of Giovanni Batista Tiepolo’s fantastical Vari Capricci (c. 1735–40) and Scherzi di Fantasia (c. 1743–50) etchings. More, though, it misses the active interplay of all of these elements. Jones’s best-known creation, his performative alter-ego Mudman, embodies the artist’s fascination with ritual, mythology, and the grotesque. Shortly after receiving his MFA from Otis Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design) in Los Angeles in 1973, he began performing as a self-described “living sculpture” in the area, wearing a contraption made of sticks and foam rubber over his mud-covered body. As the nomadic Mudman, the artist simultaneously disappeared into the surrounding landscape and announced his alienation from the average SoCal passerby.

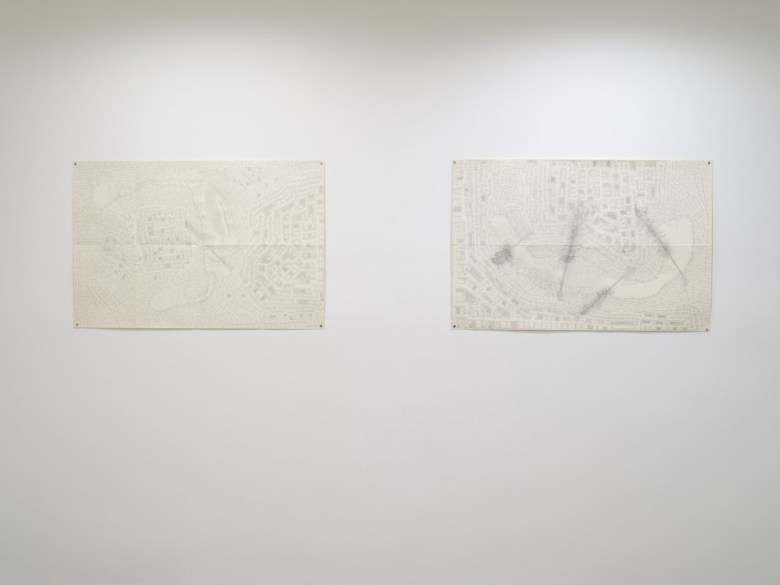

For Walking Home, his first exhibition at The Box, Jones returns to his old SoCal stomping ground with new and reworked drawings, along with sculptures, mostly composed of bound sticks that suggest barbed wire, maces, or other spiked weapons, and a video of a San Francisco Mudman performance from 1979. Jones connected with me by phone to discuss his influences, as well as “Rat Piece,” the origins of Mudman, and sexy frogs. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Natalie Haddad: From what I understand, you have both newer and older work in this show?

Kim Jones: Actually the drawings, there’s a few of them that I started around ’71, ’72. I had a lot of these drawings, so every once in a while I’d take them out of some portfolio stuffed away in storage and start working on them again. […] A lot of my art comes out of other art. The first time I heard about Renaissance or Baroque artists or Impressionists was in junior high school or high school. That’s when I started hearing about Tiepolo — Battista Tiepolo, the father, and Domenico, the son. If you get a chance to look at details of some of my drawings, it’s not like they look like Tiepolo’s, but maybe you could see the influence of Tiepolo, maybe some Baroque drawing. […]

When I was taking Saturday drawing classes in high school, my teacher knew [artist] John Altoon, who lived in Venice. He came to our class one time. He was kind of a scary guy, but I was really impressed with him. After I got out of the service, I kept looking for his work. I saw these frog paintings and the rooster paintings and drawings that he did. They’re very lively. But the drawings, they’re kind of cartoons — cartoon is the wrong term. They were beautifully drawn figures, usually sexy frogs with large penises, and roosters. The sexual revolution in the ’60s had already happened, but still to actually make things that were like that, it’s not really frowned on, but it wasn’t really encouraged. Suddenly it was like somebody gave me permission, and so I made these frog paintings. They all had large penises, and they were all drinking and having sex with other frogs and flying around. I really got my sexual energy out on those things. There was a certain point around ’72 when I got tired of it. I started reading Avalanche magazine. That’s another kind of work that I could really identify with. I just started going from there.

NH: Can I ask you about how “Mudman” came into being?

KJ: It started out around ’73 or ’74. At that time I was making sculptures that looked a little bit like Eva Hesse sculptures: bamboo and some gauze, and water-based latex and foam rubber. Finally around ’74, ’75, I went to Santa Monica College and I took a woodworking class. I made a dollhouse for my mother, three stories, and I also made the basic large structure that I kept and cut it in half many times, and put it back together again.

The head structure was foam rubber. I managed to have a little space, I think it was like $25 a month on the [Venice Beach] boardwalk. I filled it up with foam rubber and sand on the floor, and chicken wire on the walls. Most of it was just found on the street, people throwing away bed covers and all that. That’s when I started using that material to make a sculpture that ended up being the Mudman structure, the hat that I wear and the structure itself. It wasn’t until around ’75 or so that I started putting mud on my body. Before that I would just walk around with the structure on the boardwalk. I knew most of the characters there, so they accepted it; it’s like, “Oh, that’s just crazy Kim.” … The mud was a way of making me blend in more with the structure. Usually I would go to the Santa Monica mountains or sometimes to a vacant lot. I would put the mud on and walk around, mostly Venice, but also Santa Monica and LA. Anybody that wanted to talk to me, I would talk to them. I didn’t try to entertain them. I would stand and just be me. But actually doing that — people in most cases, they make a lot of assumptions, so people would walk up to me and say, “Now, is this religious? Is this political? What are you doing? And are you asking for money?”

Because I had the bucket with the mud, people thought I was asking for money, and I wasn’t. I didn’t really care. I was just showing my art on the street because there was no place else to show it. One time these three little old ladies came walking up to me. They were sort of in a line, and they were kind of bowed down trying to figure out what I was. They walked up to me and each one put a quarter in my bucket. I said, “Well, thank you.” Then, I think it was about a week later, this guy in a suit came walking up to me and said, “Boy, I’ve never seen anything like this. I’m from New York and I’ve never seen anything like this,” and he put a $20 bill in my [bucket]. That’s where the Mudman came from.

At that time, Otis was divided between very radical Fluxus and very conservative teachers that wanted you to draw and paint like an Old Master. Both sides liked me because I could draw and paint. I loved the Old Masters so I’d draw just like that, and they all thought it was great until I was taking a design class, and in the class — I think this was in ’72 — I bought a rat, and I burned it to death in the sculpture garden. This is also from Vietnam; our camp was covered with rats. That was our entertainment in Vietnam at camp. I took that back to LA in the ’70s, and they didn’t like that at all. They threatened to kick me out of school. The sculpture teacher actually wanted to beat me up. He was so furious. […] Then Frank Brown asked me to do a performance in ’76. He was a curator at Cal State LA at that time. “Sure,” I said, “But I’m going to kill some rats.” He said, “Yeah, do whatever you want. I don’t care. Just don’t tell me.” That’s when I did the rat performance where I killed three male rats and had to go to court. A lot of people were very upset. Actually, they’re still upset. ’76 was a long time ago, almost 50 years, and they’re still very upset about that.

NH: Yes, I’ve read about that performance.

KJ: Kristine Stiles is one of the people who did the essays for the catalogue [Mudman: The Odyssey of Kim Jones, 2007], and she spent a lot of time talking about being a Marine and that war experience. You sort of bring it back and it doesn’t always fit in with the society where you’re not supposed to do that stuff.

NH: Yeah, and I’ve also read about your work associated with your experience in war, but I don’t want to presume that it’s all related to that.

KJ: Even without being in a war, I’ve always had a dark sense of humor. Even before I went into the service, my drawings were always kind of grim and dark, and leaning toward the nasty part of art, whatever you want to call it.

Kim Jones: Walking Home continues at The Box (805 Traction Avenue, Arts District, Los Angeles) through November 4. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.