David Diao loves pure abstract painting as embodied by the highly revered work of Barnett Newman and Kasimir Malevich, even as he doubts their claims of attaining the sublime or achieving a utopian, universalist language. After a well-received debut exhibition of abstract paintings at Paula Cooper gallery in 1969, along with work in the 1973 Whitney Biennial, Diao decided to stop exhibiting in the mid-1970s, when high Modernist painting was superseded by Minimalism and Conceptual Art.

To me, Diao’s withdrawal from the art world — and reentry in the mid-1980s, with conceptually rigorous works that explored high-Modernist painting’s contradictory legacies — indicates his desire to investigate painting’s multiple, competing identities. Unswayed by the orthodoxies of Clement Greenberg and Donald Judd, he knew firsthand that a painting — whatever else it is — is a vulnerable object enmeshed in a variety of overlapping systems.

By examining the information stored in these systems Diao found a way to return to painting with an unrivaled intellectual forcefulness that I think the American art world has not come to grips with. (He has had major museum exhibitions in Europe and China.) He was one of the first artists to recognize that Greenberg’s emphasis on “stain” painting and Judd’s stress on the “specific object” denied cultural difference. Exploring his childhood memories, and the spaces in which he grew up, in Chengdu, China, and in Hong Kong, he knew that he would never be accepted into the US art world unless he performed as a White abstract painter, which he refused to do.

In his diverse explorations, Diao exposes a deeply held American art world prejudice, which is that the pursuit of the optical precludes an interest in cultural upbringing and biography. This is perhaps why Jack Bankowsky, writing for Artforum (March 1990), felt compelled to characterize Diao’s career as an “extended bout with abstraction [that] constitutes one of the longer, stranger sagas in the annals of recent painting.” Diao’s bout with abstraction looks decidedly less strange when you realize that it preceded Kerry James Marshall’s engagement with Newman in paintings such as “Untitled, Red (If They Come in the Morning)” (2011).

If you want to understand what might irk the art world, you need only go to the exhibition David Diao: On Barnett Newman, 1991–2023 at Greene Naftali, which brings together 12 paintings the former has made about the influential latter artist, who produced 118 paintings between 1944 and 1970, the year of his death. Diao’s acrylic paintings incorporate silkscreen, fabricated vinyl forms, and collage — materials and processes Newman did not use. Eschewing the postmodern strategies of citation and parody, Diao looks closely at an irrefutable facet of Newman’s art and career in each work, and uses him as a sounding board to explore both his own fascination with the artist and the contradictory legacies of modernism.

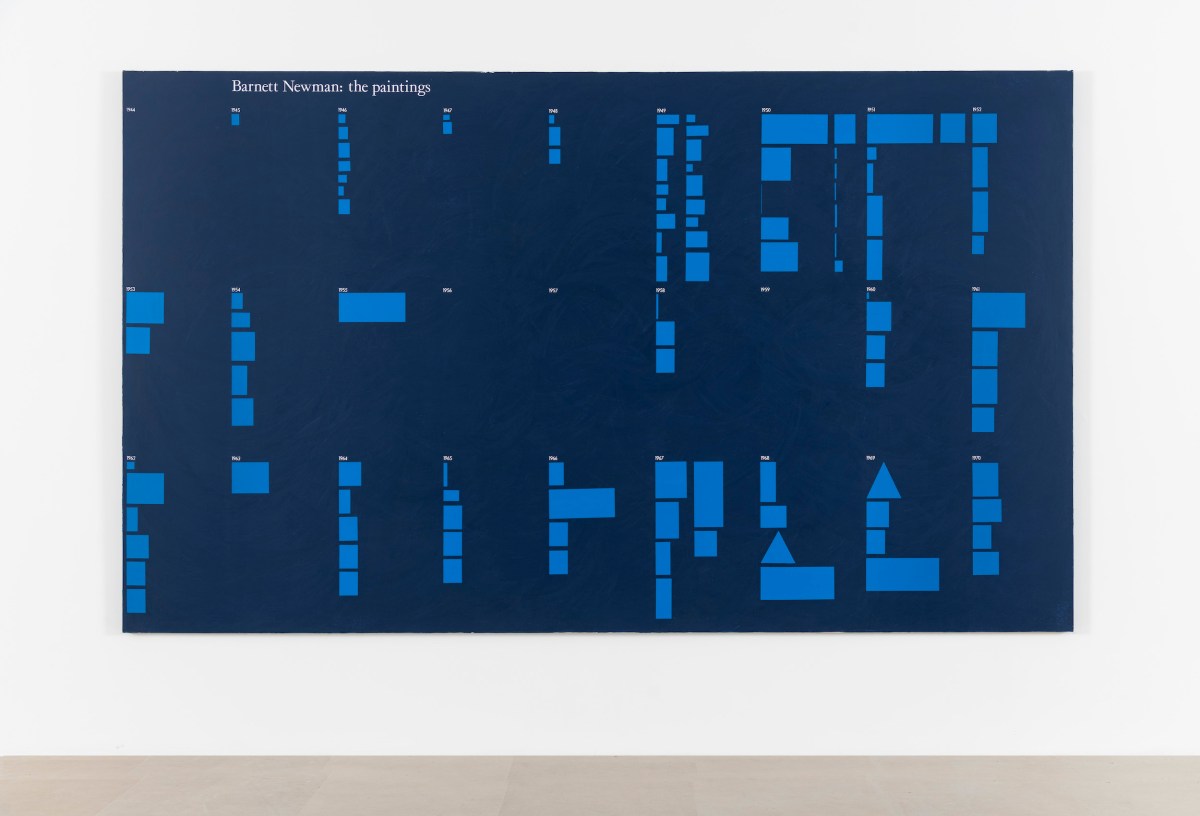

Although I had previously seen paintings from this group, I did not realize until this exhibition how thorough and open-ended this series is, or the range of ways that Diao has examined Newman’s work, relying on widely available facts, such as the number of paintings he made during each year of his career.

One of Diao’s responses to Newman seems to be puzzlement. The first painting I encountered in the exhibition was “Barnett Newman: The Sublime Is Now” (2023). Diao collaged the front and back cover of Tiger’s Eye, an artist-run magazine, along with pages of Newman’s contribution to the magazine’s theme, “The Ides of Art, Six Opinions on What Is Sublime in Art?” In 1948, three years after World War II ended and images of the Holocaust became widely circulated, I think it is fair to ask what possessed Newman to write about the sublime. The sublime is an experience that is both awe inspiring and terrifying, such as the boundlessness of the universe. What does it mean to make art that rejects all traces of history? Newman, who wanted to wrest this word out of its historical context of European philosophy, concludes his essay with this comment:

The image we produce is the self-evident one of revelation, real and concrete, that can be understood by anyone who will look at it without the nostalgic glasses of history.

If pure abstraction dispensed with figure, space, and history, what do you do after this has been achieved, especially if you are committed to painting? This is one of the questions motivating Diao.

In “Barnett Newman: Chronology of Work (Updated)” (2010), Diao is updating an earlier painting, “Barnett Newman: Chronology of Work 1” (1990). Since the earlier painting was not in this exhibition, I cannot say if the chronology was changed, but the use of “updated” suggests that new information prompted changes. At the same time, his use of charts and diagrams calls their accuracy into doubt. For all the fixedness of the “verifiable information” he includes, he knows we live in a fluid world and that change is the only thing that is permanent. What the updated version does convey is Diao’s sense of humor about his undertaking, which further adds to the complexity of his engagement with one of the pillars of Abstract Expressionism.

Diao uses a catalogue in his possession as the basis of the painting “BN: Spine 2” (2013). A jagged white line, echoing Newman “zips,” bisects the purple rectangle (a color in which he never painted). While Newman achieved a retinal vibration with large expanses of unmodulated color, dematerializing the surface in his late paintings, Diao applies his acrylic layers with a palette knife, merging color and materiality into a tight skin. By looking to a purple catalogue for the painting, Diao reminds us that facts may be neutral, but which facts are selected and how they are presented are not.

Diao’s multilayered engagement with Newman is one of the high water marks of painting in the past 30 years. His scrutiny of painting’s promises and doubts never leads him to a conclusion. That ambivalence sets him at odds with many of his contemporaries. Exploring race, the history, of abstraction and utopian thinking, childhood, and pop culture, plus his own life as an artist living in the diaspora, Diao is a major figure in art. It is time we recognize and celebrate that.

David Diao: On Barnett Newman, 1991–2023 continues at Greene Naftali (508 West 26th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) though January 13. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.