Many artists feel pressure to live a certain kind of life in order to fulfill the societal expectations and stereotypes that come with the occupation — the images we see of artists are often free-spirited, bohemian, and especially in the case of women, child-free. While some may delay or opt out of parenthood out of genuine desire, many do so because of financial instability or fears that it will hurt their career. These fears are understandable and deserve empathy, though I would argue that one of the great blessings of being an artist is explicitly facing your fears, and many people feel that becoming a parent has made them more successful, either because they felt an increased pressure to get their career together or because they simply felt more fulfilled. Everyone has a different vision of what success means to them, and this vision usually changes multiple times throughout life.

Around the age of 34, I started to experience a kind of mental fertility crisis. The onset was shockingly fast; it was as if one day I was vaguely thinking about whether I would like to have a child someday, and the next I had to find the closest Y-chromosome available to help me because the situation was literally do or die. While that feeling might not be an accurate reflection of reality, fertility outcomes vary wildly between individuals, it is certainly one that many women experience. And while some have children later in life, as celebrities who have access to expensive world-class healthcare often remind us, many other women’s fertility declines sharply past the age of 35.

I tossed around the idea of freezing my eggs — first suggested to me by an older relative who regrets not doing so — for years before I went through with it. The main prohibitor was the cost, but the decision gave me anxiety for more than financial reasons. It felt like a mid-life crisis of sorts in which I re-evaluated all of the choices I had made in my life, including the romantic relationships I had been in, my career priorities, and even my decision to become an artist in the first place. If I was so confident in the way I had lived my life, why was I feeling such a looming sense of regret and disappointment? Why was this manifesting in a borderline obsessive focus on the viability of my eggs and whether or not I would have a child? I shared my predicament with a male friend, asking him, “How would you feel if someone told you you could run out of semen in a few years?” He replied, “I’d feel like having a baby.” Exactly.

Part of my decision ultimately came back to my love life and my specific desires: There were ways for me to have a child right then, either through artificial insemination or rushing the partnership process with someone willing to do the same, but neither of these options appealed to me. I wanted more than a just “baby” as some kind of trophy or life prize. I wanted to give myself more choices, more agency, and, if it was not obvious enough already, more time. I had learned so much about how to treat myself and others, about intimacy, responsibility, and communication, that I wanted to give myself a chance at building a partnership in which I could make these decisions with someone I love. I wanted the freedom to contemplate not going this route at all, leaving myself open to the myriad of ways in which a person can lead a joyous, fulfilling life and contribute meaningfully to the world on their own. The problem was that nothing felt like a choice under the pressure cooker of my biological clock, it felt like a series of triggers, reactions, and fear responses.

So, after much (maybe too much) thought, I decided to bite the bullet, spend the money, and shoot myself up with an inordinate amount of hormones designed to temporarily turn my body into a veritable chicken coop. The hormone injection was an initially scary process, but ended up being weirdly comforting, almost like the soreness you feel the day after an intense workout. Yes, it was disagreeable at times, but it also served as a physical reminder that I was honoring myself and my goals. I was a high responder, which means I developed a lot of follicles; toward the end of the process, my ovaries were so big I could literally feel them in my body. It’s an incredibly strange sensation. Not a bad one, just strange. They thudded, swollen deep inside me, every time I took a step, and ached anytime I moved. Needless to say, I scheduled a lot of downtime.

Throughout my trips to the fertility clinic, it dawned on me that this was not only a process I would likely never go through again, but also that, conceivably, I was experiencing the first steps of giving life to my future child. It seemed important, special even, to document the process for myself and this potential future family. Everyone wants to be wanted. What could be greater evidence of being wanted than your mother spending an inordinate amount of time and money for the possibility of giving life to you? If nothing else, it was an important moment in my life when I permitted myself to go after what I wanted, rather than passively allowing my biological clock to tick by.

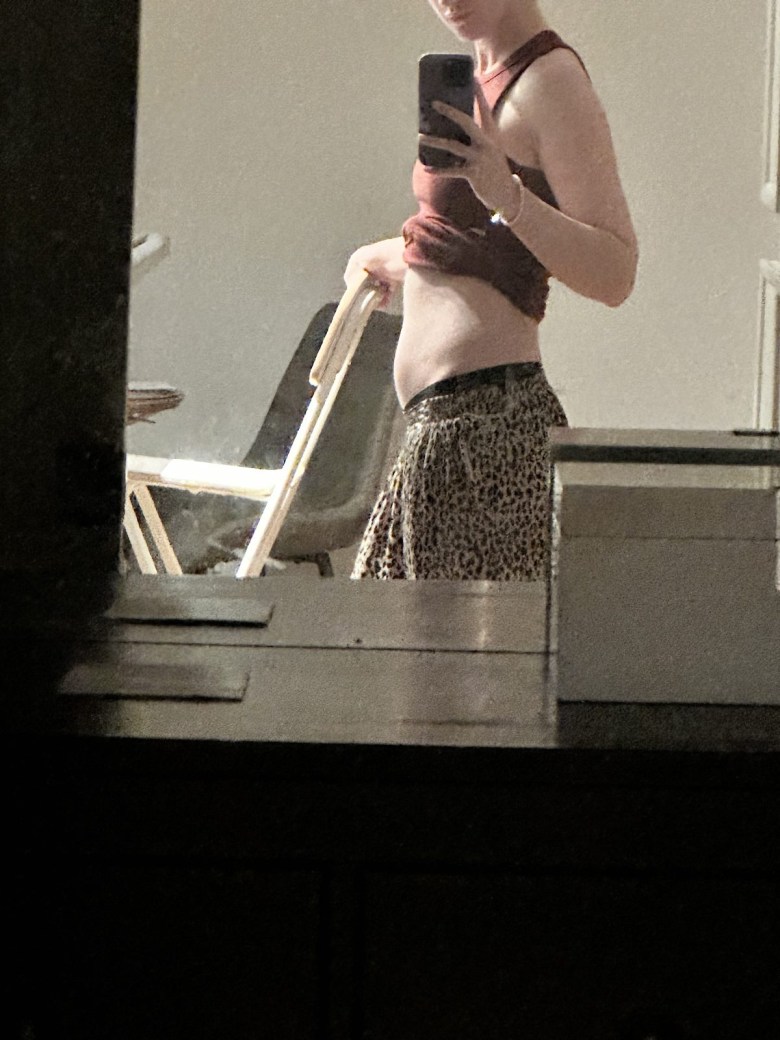

I began snapping pictures, but rather than conventional images, such as a posed shot with my doctor or a selfie in front of the fertility clinic, I wanted the photos to convey how the process really felt: my physical and psychological vulnerability, my cautious excitement, my extreme focus on the goal. This centeredness is most vividly on display in “Q-cap” in which my eye contact is completely divorced from the viewer and instead totally fixated on preparing the injection I need to stimulate my follicles (all 2023).

I, the subject, could not be bothered with anything else; the only thing in the world that existed to me was those eggs. In other works, such as “Stirrup” or “Follicles” the viewer gets a glimpse of how invasive and clinical this experience can be, how I had to undergo medical evaluations, having my body prodded and measured, amidst so much emotional turmoil and uncertainty.

In “Belly 1” and “Belly 2”, however, the viewer finally gets some emotional relief, as I flash a subtle smile and peaceful gaze that communicate that despite it all I am feeling a sense of deep serenity and poetic pride.

While I was taking these pictures artfully, art truly was one of the last things on my mind during this time. I had hormones to inject, vitamins to take, and a ride to secure to and from the doctor’s office as I went in for “harvesting.” The procedure, performed under anesthesia, went well, and after recovering, I returned to the images wondering what I would do with them. After yet another push through fear, centered this time around social judgment and medical privacy, I decided to share them as artworks on Instagram, with further instructions in my stories that anyone who wanted could DM me their email address for an essay outlining the details, tips, and tricks of my experience. The response was overwhelming, and part of the reason I am writing this essay. Many, many cis women, trans men, couples, and others are interested in this procedure, and there is no point or beauty in gatekeeping fertility.

While my procedure went well, having frozen eggs is not a guarantee of motherhood, though at this point you have probably realized that is not all this experience meant to me. Ultimately, this choice had as much to do with giving myself permission to go after the things I wanted as it did with fertility. It had to do with believing in myself and accepting uncertainty, along with making the best and wisest decision I could given the information I had at the time. This kind of self-love is incredible to experience though it certainly does not have to take the form of freezing your eggs. I did it, and I am the better for it.