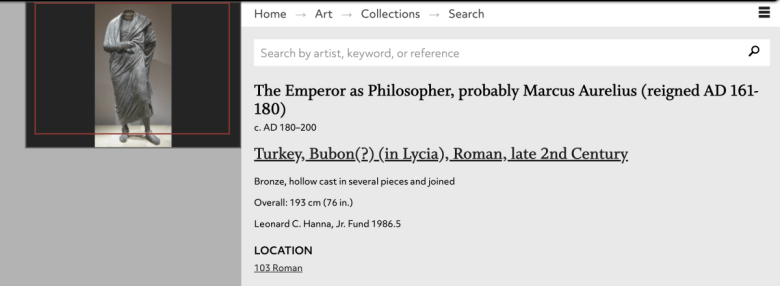

At a ceremony on December 5 at the Turkish Consulate of New York, 41 looted ancient artworks that had been recovered by the Antiquities Trafficking Unit of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office in recent months were repatriated to Turkey. Among these were eight bronzes that originated in the ancient Roman city of Bubon in the mountainous southwestern region near modern Burdur. These include pieces handed over by New York’s Fordham Museum of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Worcester Art Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Noticeably absent from the group, however, is the statue known until recently as “The Emperor as Philosopher, Probably Marcus Aurelius,” at the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), by far the largest, most significant, and most impressive work associated with Bubon in any American museum. Unlike other museums presented in the past year with evidence that they owned works looted from this site, the CMA opted not to surrender its piece immediately. Instead, the CMA has filed a lawsuit against the Manhattan District Attorney, seeking a declaration that it is the “rightful” and “lawful” owner of the headless bronze statue that has been the centerpiece of its Roman collection and one of the museum’s star attractions since 1986. The CMA claims that the connection between their statue and Bubon is unproven. However, there is far less uncertainty about the piece’s provenance and identification among experts than the museum suggests.

In May 1967, Turkish authorities, acting on a tip about archaeological looting, discovered a stunning, over-life-sized nude bronze statue hidden in the tiny village of İbecik. Villagers led them to a fresh pit at the nearby Roman site of Bubon. Archaeologists soon arrived and uncovered a large, two-sided platform and several free-standing statue bases. These were inscribed with the names of 14 Roman emperors and empresses, the footprints of the statues that once stood atop them clearly visible. Another inscription identified the structure as a shrine to Rome’s rulers. But the statues had all disappeared, except for the one the authorities seized, which is today in the Burdur Archaeological Museum.

Meanwhile, starting in the mid-1960s, an extraordinary number of extremely rare ancient bronze statues and Roman imperial portrait heads began showing up out of nowhere on the art market. Several — possibly all — were handled by the notorious antiquities trafficker Robert Hecht. The pieces surfaced slowly and singly until a bold, young Boston-based art dealer named Charles Lipson bought four statues in Switzerland in late 1967. Three of them portray idealized nude male figures in contrapposto stances with their right arm raised. One of the nudes still has its head and is recognizable as the Roman emperor Lucius Verus. The fourth figure wears the mantle and adopts the pose typical of ancient philosopher portrait statues.

Cornelius Vermeule, a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston at the time, was the first to discuss Lipson’s bronzes in public. In talks and publications in 1967 and ’68, he divulged details that may have come from Hecht, including the statues’ discovery in southwest Turkey, their connection to a handful of other recently-surfaced bronzes, and the identity of one of the headless nudes as Septimius Severus (Hecht would later sell a bronze head of that emperor to a Danish museum, presumably the match to Lipson’s statue).

At the time, Vermeule was unaware of the 1967 events at Bubon, and hypothesized that the bronze group came from a different site in the region, the ancient city of Cremna, whose recent looting was widely known. But in the 1970s, Turkish archaeologist Jale Inan began studying the connections between the recent art market bronzes and the one seized by Turkish authorities in 1967. In 1978, she published a lengthy scholarly article in the Istanbuler Mitteilungen matching the bronzes to particular inscriptions on the plundered statue bases at Bubon.

Even before this connection was made, Lipson had been struggling to sell his statues, which he’d borrowed heavily to acquire. The art world of the 1960s and ‘70s is hardly remembered for its deference to cultural patrimony laws. But even by the lax standards of that era, Lipson’s bronze quartet was beyond the pale. Good-faith antiquities buyers could convince themselves that a single, unprovenanced piece might have come from an old, forgotten aristocratic collection. But it’s much harder to sustain that belief in the face of four previously unknown, extremely rare statues of outstanding quality that surface out of nowhere all at once. Such a group can only be a recent, illicit discovery.

It took Lipson 18 years to find buyers unfazed by these issues. Finally, in 1985, the collectors Leon Levy and Shelby White, a trustee at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchased the Lucius Verus statue (seized from her home by the Manhattan DA in 2022 and repatriated last year). The New York dealer Edward H. Merrin took the rest off Lipson’s hands, brokering the sale of the clothed figure to the CMA in 1986 and buying the other two himself in 1987. These two circulated among private collectors for years. One, which had been on a long-term loan to the Metropolitan Museum, was seized by the Manhattan DA in March and returned to Turkey; the other is rumored to be abroad. By 1988, Lipson had folded his business, apparently changed his last name, and disappeared from the art world. In 1993, Inan published a second article on Bubon with additional evidence tying the statues to the site, including new excavations, interviews with the looters, and the looters’ own handwritten notes on their finds and sales. Further evidence of the connection came out in a recent New York Times article revealing that Turkish investigators have reconfirmed the details of the looting with some of the original looters themselves.

Of particular relevance to the CMA’s case against the Manhattan DA: First, to my knowledge, contrary to the museum’s claim in the court documents that “many scholarly articles” have drawn “different conclusions about the statue’s origins,” no scholar has publicly contested the association of Lipson’s statues with Bubon since the appearance of Inan’s articles thirty years ago (she died in 2001). This is not because it is an “older theory,” as the CMA calls it in the lawsuit, and therefore irrelevant; it is because it has been, as far as I am aware, universally accepted by the field as correct. Indeed, the biggest proponent of the association between the statue and the site of Bubon was the CMA itself. The museum borrowed the Bubon head at the Worcester Art Museum to display alongside their statue when it debuted in 1987, along with photos of other Bubon pieces. They also sent their own curator, Arielle Kozloff, on a research trip to Bubon to learn more about the piece’s origins. Kozloff published an article in the museum’s scholarly Bulletin hypothesizing when and why the statues were set up there in antiquity (but never questioning that this was where they had been found by looters in the 1960s, contrary to the misleading insinuation of the CMA’s court filing). She even thanked Hecht for information in the acknowledgments.

The museum claims in its lawsuit that based on “subsequent research,” Kozloff has had a change of heart, and that “she now believes that the Philosopher did not come from Bubon and that any previously stated connection between Bubon and the Philosopher was mere conjecture.” This alleged “subsequent research” has never been published, however, so there is no way to know when, why or based upon what evidence it was undertaken and no way to assess its merits. Nor has the museum ever put forward an alternative account of the statue’s origins.

The “subsequent research” also apparently extends not only to the matter of the statue’s origins but to its very identity. For 36 years, in all of its public communications about the statue — the acquisition press release, multiple articles by Kozloff, handbooks, gallery labels, webpage text, and videos — the CMA identified the statue not as a Greek philosopher (which the costume and pose might suggest) but rather as “probably” the Greek philosophy-loving Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. This identification is supported not only by the statue’s impressive scale and quality, but also by its association with Bubon, where there is an empty pedestal inscribed with the name “Marcus Aurelius.” Again, contrary to the claims of the CMA court filing, the identity of this statue as a Roman emperor has never, to my knowledge, been questioned in print since Inan’s articles. Not, that is, until this summer, when, without any explanation, this well-established, longstanding identification was hastily scrubbed from the museum’s website and replaced with a description claiming total ignorance about who or what the statue is. Whereas the label formerly described the figure as “The Emperor as Philosopher, probably Marcus Aurelius,” and dated it very specifically to the period immediately following Marcus’ death (“180-200 CE,”) it is now given the very generic title “Draped Male Figure,” and dated very vaguely to a broad, 350-year span (“150 BCE – 200 CE”). The recent court filing doubles down on this cynical, desperate erasure of historical knowledge, a complete betrayal of the museum’s educational mission.

While deeply dismaying, it is perhaps not entirely surprising that the CMA has been so much less willing than other American museums to surrender its Bubon bronze. Most of those other pieces were gifts to those institutions, while Worcester purchased its piece in 1966, several years before its origins at Bubon were known. Those pieces are also all relatively unexceptional portrait heads or fragmentary body parts — rare in bronze but easily substituted in museum displays by other works in their holdings. Compared to those acquisitions, the risk taken by the CMA when it paid $1.85 million (an astronomical sum for an ancient work at the time) for an extraordinarily unique, monumental statue, whose likely illicit origins had been published in a major scholarly journal eight years earlier, was enormous. The Cleveland Museum of Art took a gamble in 1986 that none of its peers in the museum field had been willing to take. No other American museum would touch Lipson’s once-in-a-lifetime, life-sized classical masterpieces — not the Boston MFA, not the Metropolitan Museum of Art, not even the famously acquisitive Getty. Lipson’s statues were toxic from the start, and their toxicity has only grown in the years since the CMA made its purchase, as the public’s awareness of the destructiveness of archaeological looting, discomfort with appropriating cultural heritage, and attention to museum ethics have increased. It’s time for the CMA to relinquish its claim to this plundered artwork and allow it to be reunited with the other statues it stood beside in antiquity — before its toxins undermine the museum’s very soul.