A starscape twinkled across three screens as guests filed into the Gerald W. Lynch Theater for the multimedia performance Angel of Many Signs. Presented by the New York Choral Society, this two-show run featured the New York premiere of composer Kevin Siegfried’s Angel of Light, a cantata inspired by Shaker melodies and texts.

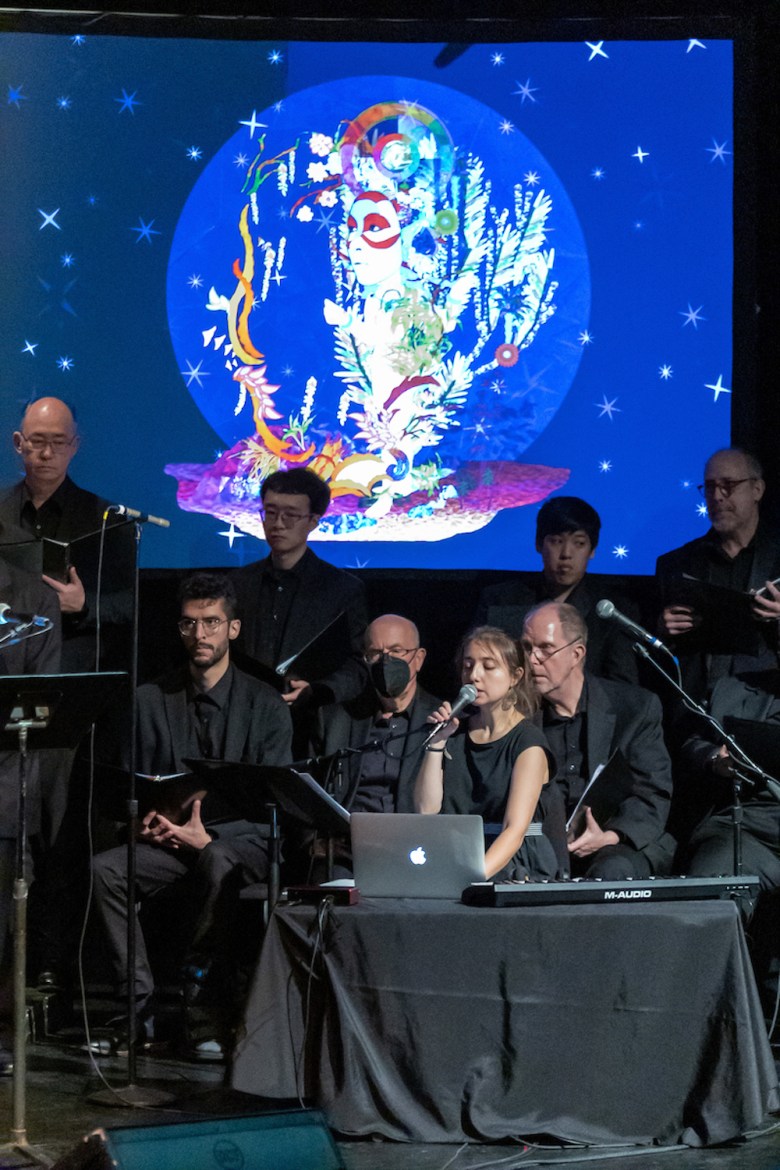

Once the overhead lights darkened, a lone figure — musician Raquel Acevedo Klein — strode across the stage. She sat down in front of a spread of tools (silver Mac laptop, microphone, M-Audio MIDI keyboard controller) and set to work. Vibrating electronic music wisped through the room, joined by Acevedo Klein’s spare, ethereal vocals. Around 150 choir members, clad in black clothes with a smattering of onyx-colored sequins, poured into nearly every available space onstage, along with conductor David Haynes, his back to the crowd. The electronica merged with Bergamot Quartet’s violins, viola, and cello, eventually giving way to soprano Chantal Freeman’s golden, ascendant voice and the choir’s rich layers of glowing tones. Mesmerizing, almost psychedelic imagery by visual artist Saya Woolfalk morphed across the screens, forming a dreamy landscape of stars, mystical symbols, plant forms, and avian figures.

The entrancing hour-long presentation brought together sacred music of spiritual women who lived in vastly different eras and contexts and experienced divine visions. Dovetailing early American hymns with medieval Benedictine chants, the show bookended Siegfried’s Shaker-inspired Angel of Light cantata with pieces by famed 12th-century German abbess Hildegard of Bingen, in arrangements by several contemporary composers (Nancy Grundahl, Tarik O’Regan, Missy Mazzoli, Ola Gjeilo, Sarah Kirkland Snyder, Faith Zimmer).

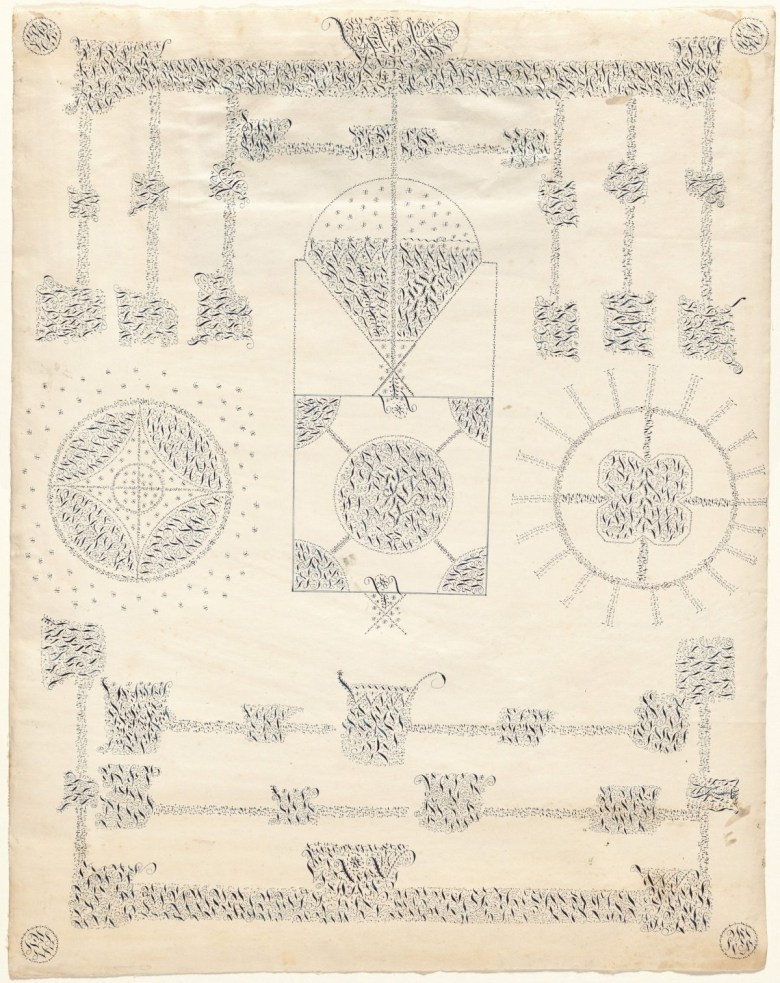

Siegfried derived the title of his cantata from “A Sacred Sheet Sent from Holy Mother Wisdom by Her Angel of Many Signs” — a Shaker “gift” or “spirit” drawing, made in 1843, when a wave of spiritualism swept through Shaker communities, starting in Watervliet, New York. During this decade-long Era of Manifestations, young girls, primarily, would enter trances and receive messages from the spirits of Shaker founders and even historical figures. Though made with ink on paper, these so-called drawings weren’t considered visual art or intended for display; they were a means of transcribing and sharing these heavenly visions. Angel of Light draws inspiration from this period of Shaker history. Told in seven parts, it opens with a choral invocation (“Sweet Angels Come Nearer”) and traces, through songs with ecstatic “spirit language” and sounds mimicking instruments, an encounter with an angel.

A detailed digital program for Angel of Many Signs (accessible via a QR code printed on a card distributed by theater attendants) emphasizes the spiritual and polymathic echoes between Shaker women and Hildegard of Bingen, noting that “as the music crisscrosses the centuries, an exploration of the divine feminine and an atmosphere of visionary possibilities will surround you.” Though viewers might not readily make these connections or follow the intended narrative without reading the show’s promotional materials or program, the performance held a lush resonance all its own. As voices, visuals, stringed instruments, and electronica melded — rising, swelling, mellowing, and taking flight again — an otherworldly sonic sphere emerged, mysterious yet inviting, a call to imagination and contemplation.