At a recent preview of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art, visitors marveled quietly at large relief stoneworks and painted ceramic vessels excavated from lost cities abandoned during the Classic Maya collapse. The galleries were softly lit if not totally dark — opening the floor for the centuries-old works to speak for themselves.

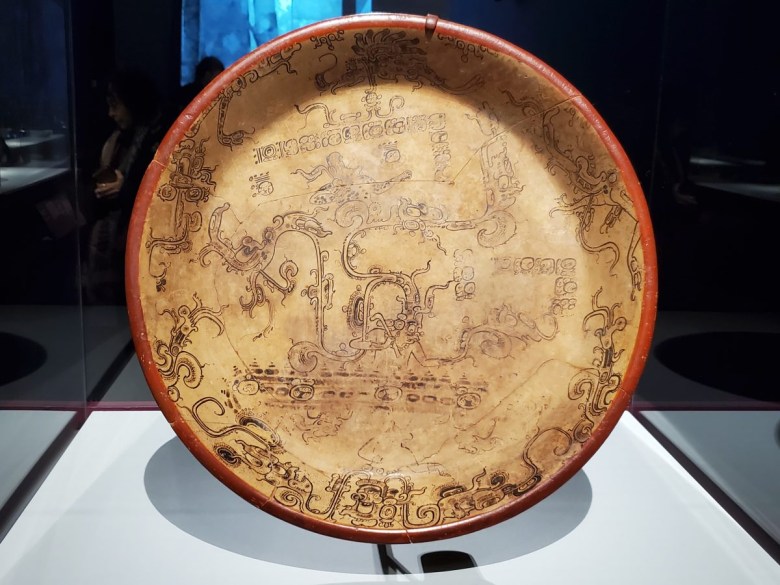

The Met’s new show, organized in collaboration with Fort Worth’s Kimbell Art Museum, features dozens of large- and small-scale sculptures documenting the histories and life stages of various Maya deities during the Classic period (250–900 CE). With both the natural decay and intentional destruction of almost all Maya texts, ancient Maya spirituality is deciphered and analyzed primarily through these precious objects. Among the vessels and ornaments in the exhibition are some inscribed or painted with glyphs and representational imagery of equal detail and quality to that of the surviving Maya codices.

“Many of the books that existed in the Classic period were probably destroyed by neglect centuries before Bishop Diego de Landa’s time,” exhibition co-curator Oswaldo Chinchilla told Hyperallergic. “The climate in the Maya region is not conducive to the preservation of organic materials especially. But these objects on display were originating from cities in ruins. The Spaniards weren’t invading these ruins, so that’s likely how these sculptures and architectural structures were preserved.”

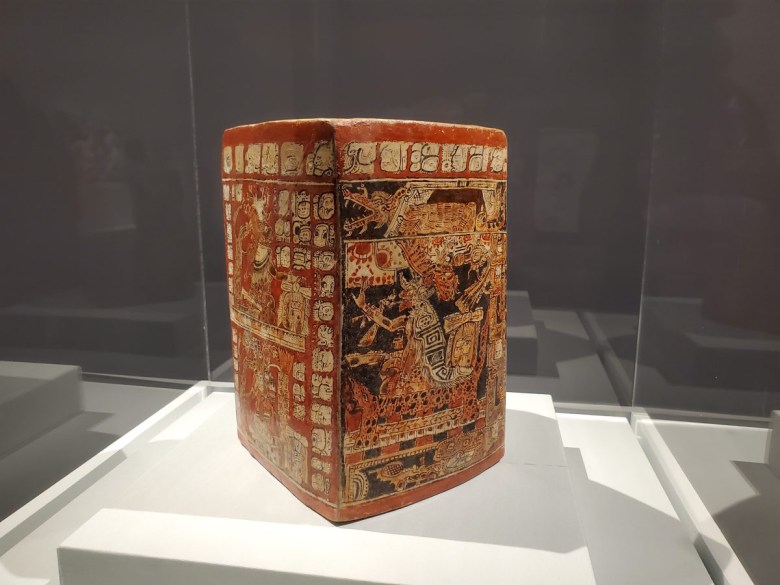

The Met has categorized the exhibition into seven major sections: Creations, Day, Night, Rain, Maize, Knowledge, and Patron Gods. The Creations section ushers visitors back to the beginning of the world through the lens of Maya archiving. At the exhibition’s entrance, a squared ceramic vessel with slip-painted imagery and glyphs depicts 11 deities convening on August 11, 3114 BCE, or the day the world came into existence, according to Maya history.

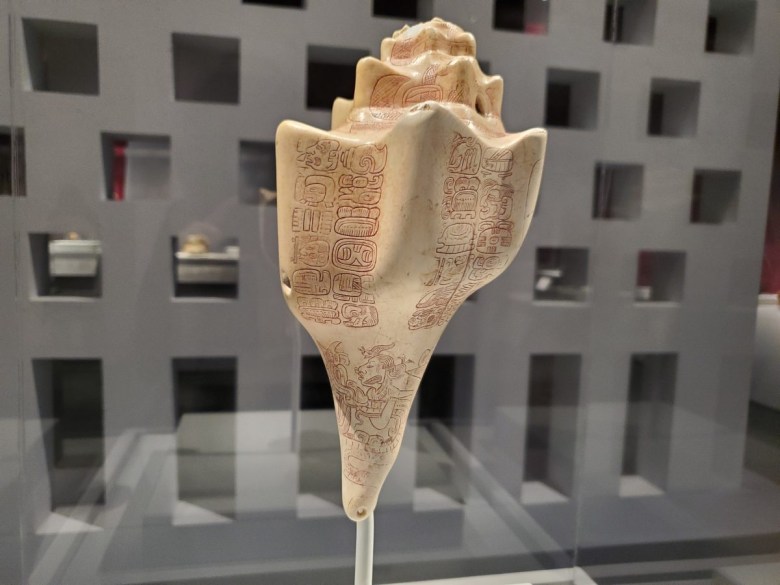

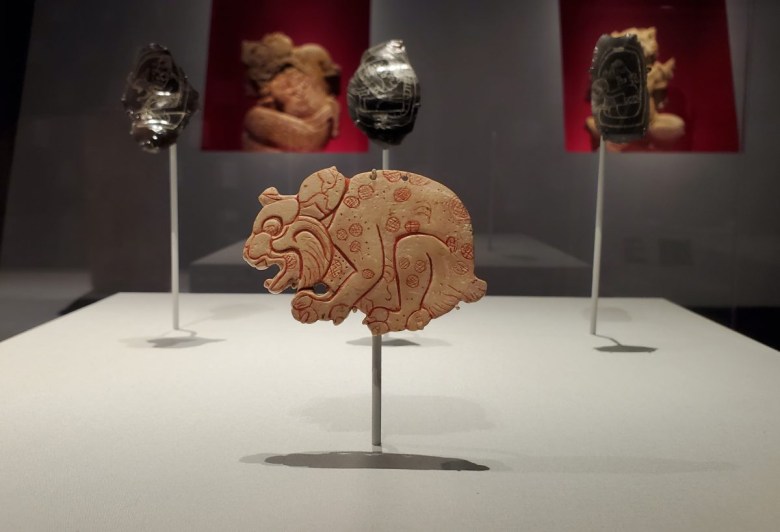

The exhibition then leads visitors through the Day and Night sections, highlighting how astrological symbolism and regional fauna are woven into the identities of Maya deities. Like many other religious systems, the sun and its associated god, K’inich, were connected with life-giving forces, while the moon goddess was represented as a young woman, broadly symbolic of reproduction and textile weaving. Both the exhibition text and the press release indicate that as nocturnal predators commonly found across Central America, jaguars were frequently represented in nighttime deities that were said to have had “aggressive, warlike personalities.” Many objects from these sections are stone relief sculptures, painted and inscribed ceramic vessels, or inscribed jade, obsidian, and seashells.

The Rain and Maize sections illuminate the relationship between the Maya people and the deities of natural resources. The maize god in particular was a large fixation for Maya artists — multiple renderings of his birth, life, and death are on display, indicating his importance and reverence as corn was a major staple in the Maya diet and economy.

The Knowledge and the Patron Gods sections depict Maya artists as established members of the Maya nobility, tasked with portraying the relationships between the ancient ruling class and Maya deities. It’s noteworthy that four of the exhibition’s works have legible signatures from contributing artists, including K’in Lakam Chahk and Jun Nat Omootz.

“Archaeological information suggests that these artists were members of the royal courts, producing work for the royal patrons and kings,” Chinchilla told Hyperallergic. “So, in some sites archaeologists have located houses that were probably occupied by scribes and artists, sometimes very close to the royal palaces.” He added that the researchers found tools including conch shell ink pots containing multiple chambers.

“Some of those have the remains of the pigments that they were using,” Chinchilla continued. “Small hatchets were found for carving, as well, and mortars and pestles for grinding down pigments.”

The exhibition includes a film component documenting a religiously significant performance called the “Dance of the Macaws.” A resilient tradition withstanding the Spanish Inquisition, the dance originated in Santa Cruz, within the Verapaz province of Guatemala. The participants, made up of the young members of the community, wear ornate scarlet robes along with adorned masks with hooked beaks, emulating the appearance of the macaw. According to the description provided by The Met, the dance illustrates the “origins of social institutions and the rationale for religious rituals dedicated to the gods of the earth and the mountains.”

A clip of the video is displayed during the exhibition in the Patron Gods section, but the whole video is available on The Met’s YouTube channel. The exhibition runs through April 2.

Given how extensive the exhibition is in regards to detailing Maya history, it was disappointing that only the introduction text at the entrance, and not individual wall labels, was available in Spanish. Spanish-speaking visitors were invited to scan a QR code to access all of the exhibition texts and object descriptions in Spanish via a 106-page PDF.

That said, being able to view Maya artwork discovered from the ruins of abandoned cities was truly humbling. The confidence and care channeled through each inscription, painted line, and sculpted feature speaks to how artmaking was a divine act for Maya artists. While The Met upholds the Stelae and large, limestone throne as the stars of the exhibition, I was most charmed by the smaller, detail-oriented sculptures and ornaments — most specifically, this Maya Blue ceramic crocodile that doubled as a whistle and a rattle. Second in line was the Conch Shell Trumpet, because I was blown away by its decisive, intricate carvings upon such an unforgiving, dimensional surface.