In 1926, Italian Futurist painter Fortunato Depero debuted “Squisito al selz” at the 15th Venice Biennial. The painting advertised Campari, a popular Italian aperitif, and belonged to a genre Depero called quadro pubblicitario or “advertising painting.” Depero’s Biennial presentation was an offshoot of a half-decade collaboration between the artist and the brand; in 1924, he was put in charge of the company’s advertising brand and campaigns, and produced many materials for them in his signature style.

The fine art crossover of Depero’s commercial work triggered a movement within avant-garde Italian art that lasted a solid 30 years, through Italy’s economic boom in the decade following the end of World War II. This blurring of influences between experimental art and advertising is the subject of an upcoming exhibition at the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) in New York. From Depero to Rotella: Italian Commercial Posters Between Advertising and Art opens mid-February at CIMA and will feature nearly three dozen examples of art that bridges publicity and aesthetics.

“As Italian novelist and public intellectual Italo Calvino once explained, after the war everyone had a great desire to communicate, to tell stories, to try and make sense of everything they had just lived through,” Nicola Lucchi, executive director of CIMA and the show’s curator, told Hyperallergic. This instinct for storytelling often seeped into the industrial and commercial realms.

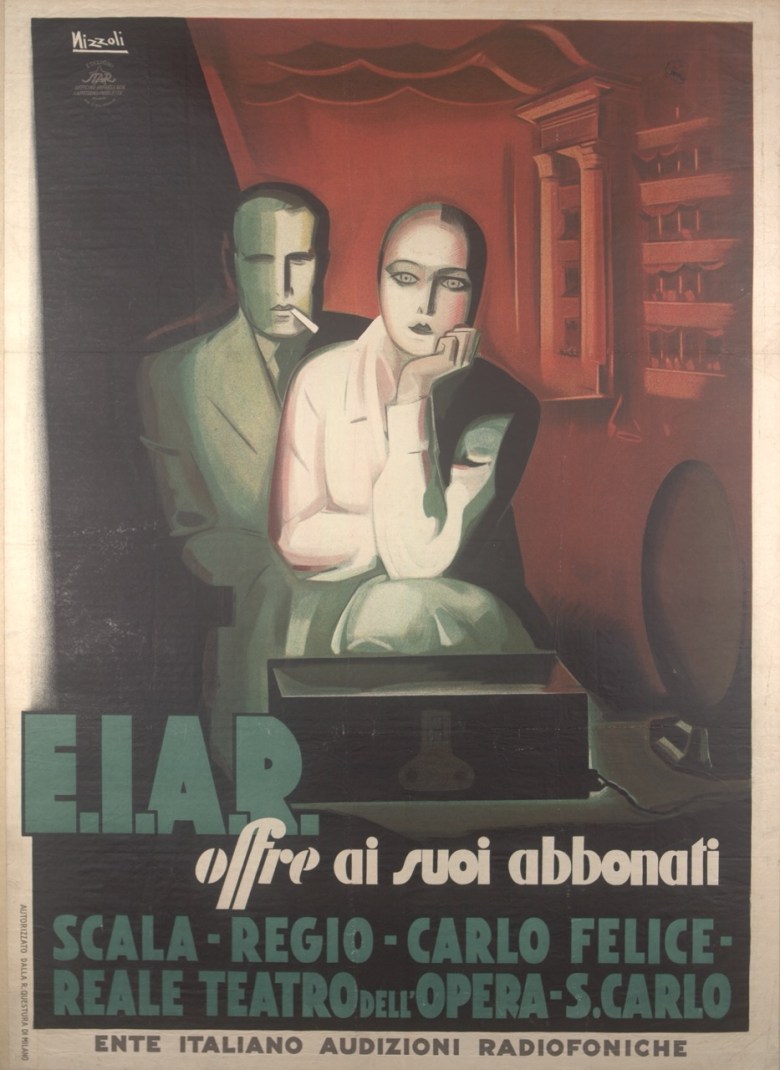

“Some of the industry captains that had a primary role in this era were socially minded humanists, and they encouraged the participation of artists in their corporate endeavors, sometimes even to the detriment of business, but in the hopes of giving capitalism a humane character,” Lucchi said.

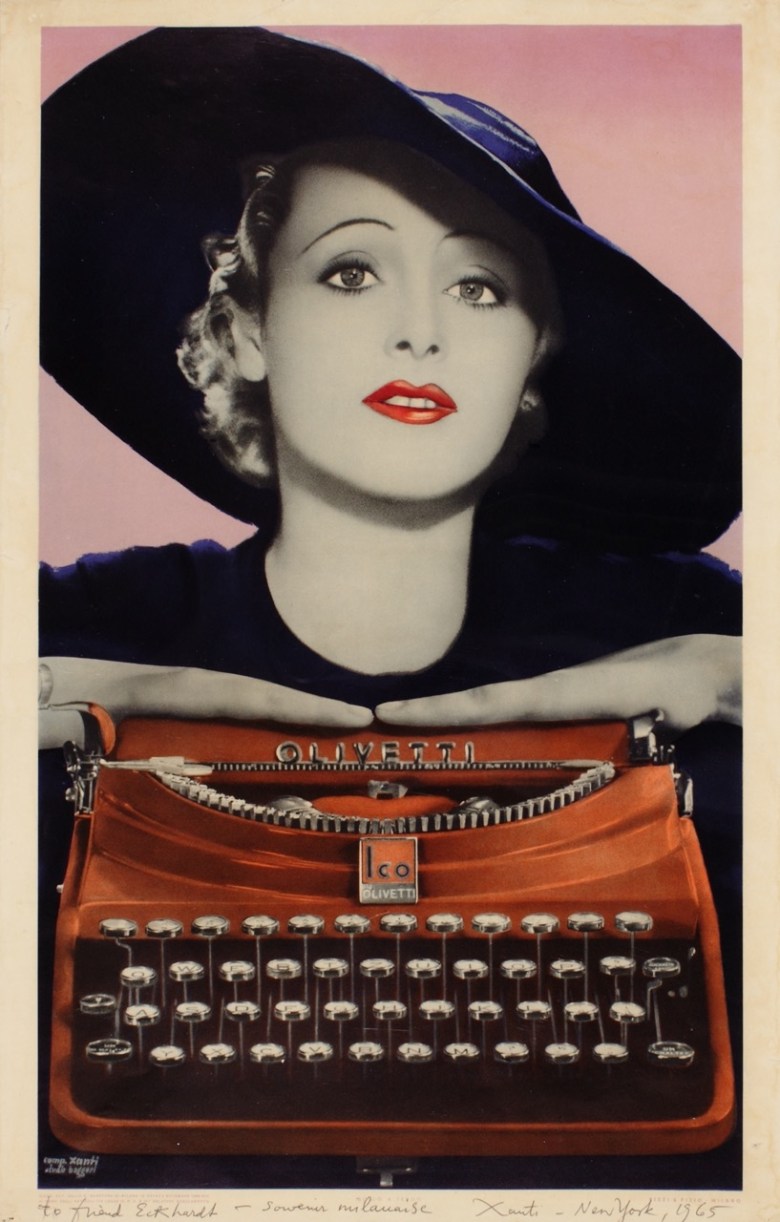

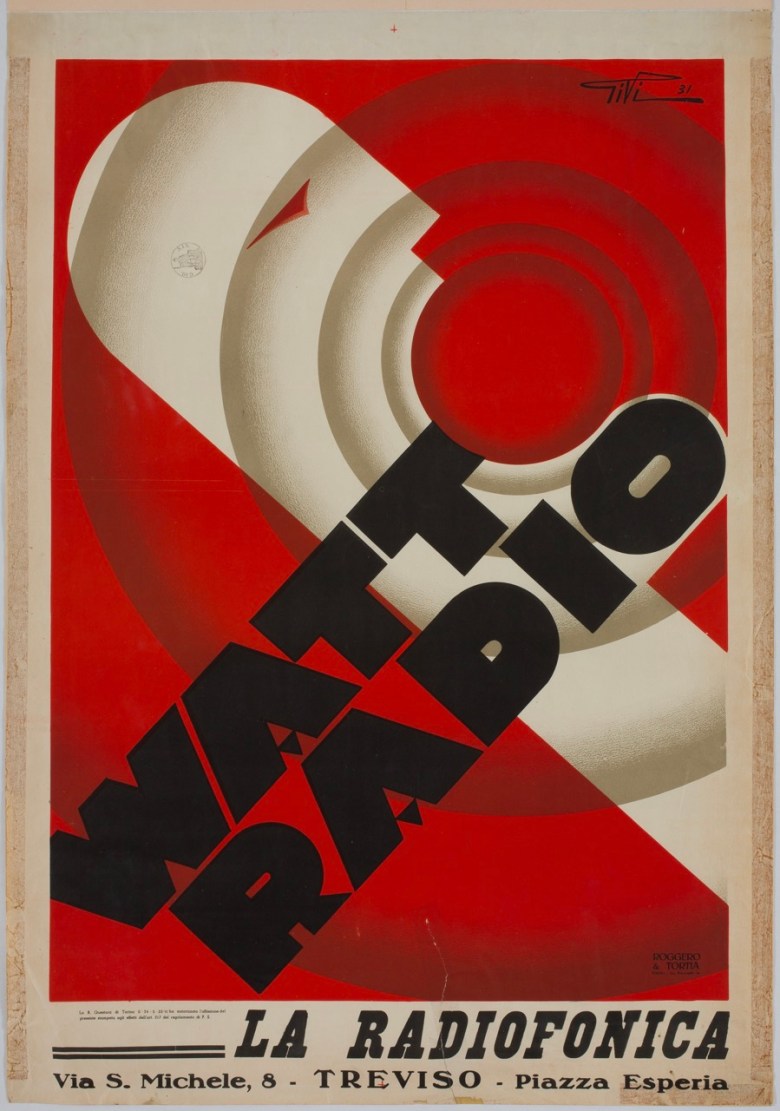

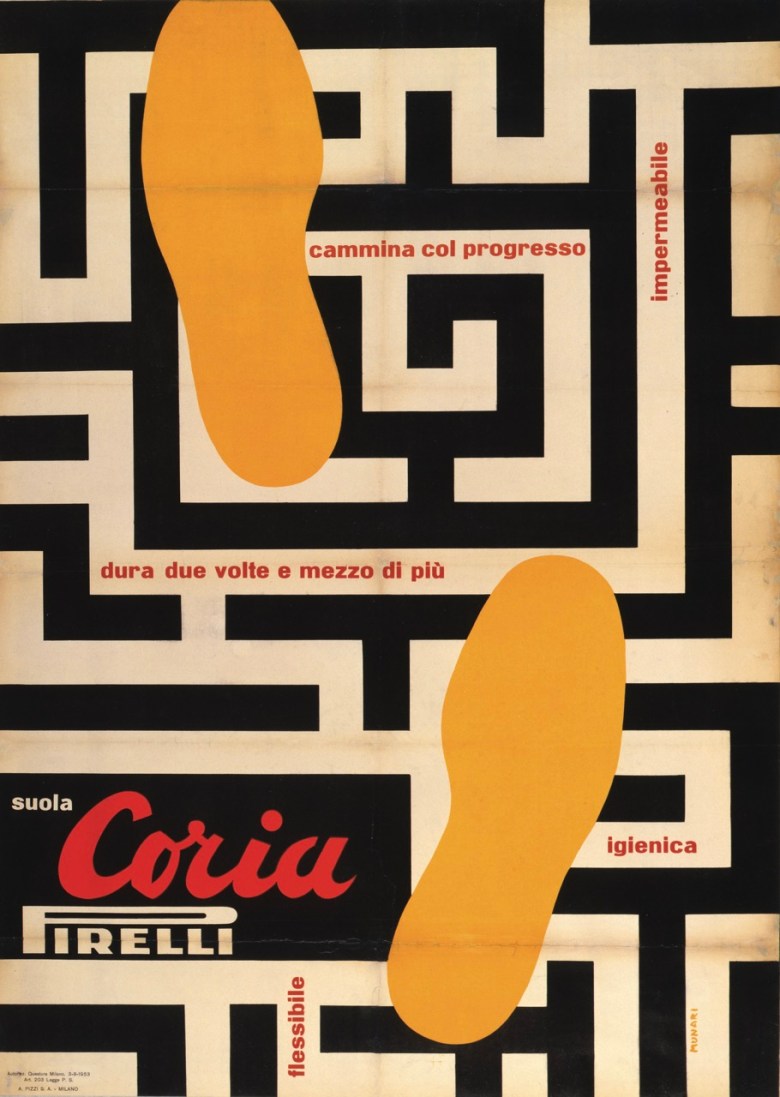

From pasta, to men’s hats, to theater performances, to typewriters, and beyond, artists of the time applied modern aesthetics to create graphic, engaging, color-blocked posters (among other advertising materials) that not only forwarded Modernist and Futurist thinking among artistic circles into the common visual vernacular, but made advertising a form of artistic expression in its own right. New headway was made by Depero and his fellows, regarding lithographic techniques, photomontage, and typography. These techniques and artist vision promoted the products of iconic companies integral to Italy’s economic boom, including Barilla, Campari, Olivetti, Fiat, and Pirelli.

Among the highlights of the show is an Olivetti typewriter poster designed by Xanti Schawinsky, a Polish-Jewish stage designer and experimental photographer who joined the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau.

“He reached Italy in 1933 as he sought to escape the rise of Nazism in Germany. At that time, Fascist Italy must have seemed the lesser of two evils,” Lucchi said. “In Italy, he settled in Milan and joined Studio Boggeri, Italy’s first major advertising firm. While he remained in Italy only three years before emigrating to the United States, the influence he had on Italian artists and graphic designers of the time had an impact for decades to follow.”

From Depero to Rotella, up through June 10, 2023, features numerous posters from major Italian institutions and corporate collections as well as private collections in the United States made by a cohort of artists including Erberto Carboni, Fortunato Depero, Nikolai Diulgheroff, Lucio Fontana, Max Huber, Bruno Munari, and many more.

Editor’s note 2/27/23 6:05pm EST: This article was updated with comments from CIMA Executive Director Nicola Lucchi.