LONG BEACH, Calif. — For 50 years Los Angeles-based artist Judy Baca has been creating sites of public memory. Through her collaborative murals, multimedia art, and teaching she has redefined what it means to work at the intersection of art and activism. Now, for the first time, you can visit a retrospective exhibition that celebrates her impressive career.

Judy Baca: Memorias de Nuestra Tierra, a Retrospective, on view at the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) in Long Beach through January 2022, is co-curated by MOLAA chief curator Gabriela Urtiaga and guest curator Alessandra Moctezuma, the gallery director at San Diego Mesa College, who came to know Baca as her painting assistant in the 1990s. While Baca is best known for her large-scale public murals, this exhibition highlights the expansiveness of her practice, bringing together more than 120 works in a range of media including painting, sculpture, installation, and a series of intimate works on paper that have never been publicly shown.

Eschewing the white box, as Baca has done throughout her career, the curators painted the galleries various shades of red, blue, and yellow, and the convictions that once kept Baca out of the mainstream art world — her entrenchment in community activism, collaborative practice, and commitment to amplifying marginalized voices — are what give this presentation its undeniable power. Despite the importance of Baca’s work, and her influence on a generation of students as a professor in the Cal State and University of California systems, decades of entrenched art-world racism, gender bias, and resistance to overtly political displays in art have delayed a comprehensive treatment of her career until now.

Coming of age in the late 1960s, Baca was active in Los Angeles’s anti-war, feminist, and Chicano civil rights movements. She knew she wanted to be a different kind of artist. “I somehow wanted my work to matter. I didn’t want to create work that went to white boxes,” she explained to me when we spoke. “I wanted to make work to go to where my family was and where my community was.” Baca began her studies at California State University Northridge in the wake of the 1965 Watts Rebellion, a six-day uprising precipitated by police violence against residents of the predominantly African American neighborhood (where Baca spent her early childhood). In 1970, a year after completing her BFA, she joined the Chicano Moratorium, which brought out massive numbers of Chicano protesters in opposition to the war in Vietnam and its disproportionate toll on the Chicano community.

Baca has maintained her activist commitments for the last half-century, developing an art practice that is reciprocal, restorative, empowering, and deeply rooted in generosity and respect. “The good news for us is that Judy has always been there,” Urtiaga told me. “She is always working for others.” Images of everyday people — laborers, migrants, mothers — are activated in works of art that draw directly from the experiences of disenfranchised communities. “Josefina: Ofrenda to the Domestic Worker” (1993) pays homage to these essential workers — almost always women, and too often rendered invisible. In the Womanist gallery (Moctezuma uses Alice Walker’s term “womanist” rather than “feminist” to include “the experiences of women of color”), we see other representations of female empowerment produced throughout Baca’s career, like “Hijas de Juarez” (2002), a sculptural tribute to the hundreds of women murdered in the border town during the late 1990s.

A version of one of Baca’s most enduring womanist works, “Las Tres Marias” (1976), recreated especially for the retrospective as “Las Tres Forever” (2021), anchors the gallery (COVID-19 restrictions prohibited the inclusion of the original, which is in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum). The freestanding three-paneled sculpture features two archetypal images of Chicana power and rebellion — the 1970s ‘Chola’ and the 1940s ‘Pachuca’— separated by a mirror. The back sides of the panels are upholstered in red velvet, “tuck and rolled” in the style of a classic lowrider. The work both contains the viewer within the prescriptive patriarchal confines of the virgin/mother/whore paradigm and urges a redefinition of Chicana identity on one’s own terms. “Las Tres Marias” originated as a component of a performance presented at one of the earliest exhibitions of Chicana art in Los Angeles, Venas de La Mujer, in 1976. The exhibition, which Baca co-curated, was mounted at the Woman’s Building, a West coast hub of the feminist art movement. During the performance, Baca transformed herself into the Pachuca in front of a backdrop that included a collaborative mural produced by the Tiny Locas, a group of young Chicanas from Pacoima.

A celebration of a different kind of female power is on view in the double-sided triptych “Matriarchal Mural: When God Was a Woman” (1980-2021). This career-spanning work began as a collaborative endeavor in 1980, and when funding dried up a few years later, the unfinished piece was moved to storage where it remained until this exhibition provided an impetus to complete it. “I was amazed at how much it resonated with the moment,” Baca told me. “I’m thinking about global warming. I’m thinking about the fact that so much of our world has suffered from male leadership … The notion that it was power over everyone and over things … we lost our compassion.”

This belief in the inextricable connection between all living things anchors Baca’s activism and her art and is also embedded in the exhibition’s title. Memorias de Nuestra Tierra translates to “memories of our land,” and refers not only to our collective memories of the places we claim, but the memory of the land itself as an index of history. In Spanish it is more expansive, as Moctezuma points out. “Tierra” also means earth — the land we share, briefly, but do not possess. “We are temporary residents,” said Baca. “We are made of this earth … we’ll be returning to it … and [we] need to reconnect in a really substantial way to keep our planet from destruction.”

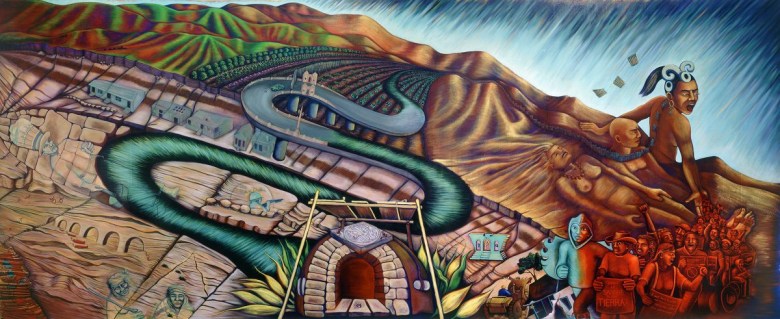

Baca’s drive to repair the relationship between humanity and the natural world is visible across the exhibition. She has spoken about it often in the context of her earliest and largest mural, her magnum opus “The Great Wall of Los Angeles” (1976-1983), which was painted in collaboration with over 400 local youth, 100 scholars, and 40 artist assistants in a paved flood channel of the LA River. “The moment I stepped into the edge of the river and imagined that it was a tattoo on the scar where the river once ran, that was the beginning of the artwork,” she told me.

“The Great Wall” was the first project Baca executed through SPARC (Social Public Art Resource Center), the organization she co-founded with artist Christina Schlesinger and filmmaker Donna Deitch in 1976, and it is emblematic of Baca’s particular brand of community-based collaboration. SPARC’s mission has since been to produce and support such collective public art projects across Los Angeles, and to involve local populations in the process. It remains one of the longest-running artists’ organizations in Los Angeles today.

In addition to the murals, the exhibition includes compelling sculptures that emphasize the fluidity of Baca’s notion of “site,” turning familiar objects into active loci of protest, contestation, and decolonization. A history of US immigration policy is tattooed across the backs of the workers painted on Baca’s “Raspados Mojados” (1994), a street vendor cart that she transformed in response to discrimination and violence against Los Angeles’s vendedores, and by extension the Latinx presence in public spaces. While working with border communities in the early 2000s, Baca was repeatedly confronted with Pancho sculptures — ceramic figurines of faceless Mexican men dozing under large sombreros. The kitsch objects, long popular with American tourists, have a multifaceted history, which includes their propagation of insidious stereotypes such as the lazy or drunk Mexican. Baca’s interventions transform the Panchos into symbols of strength and endurance, recording the struggles, sacrifices, and triumphs of migrants on the bodies of the figures themselves.

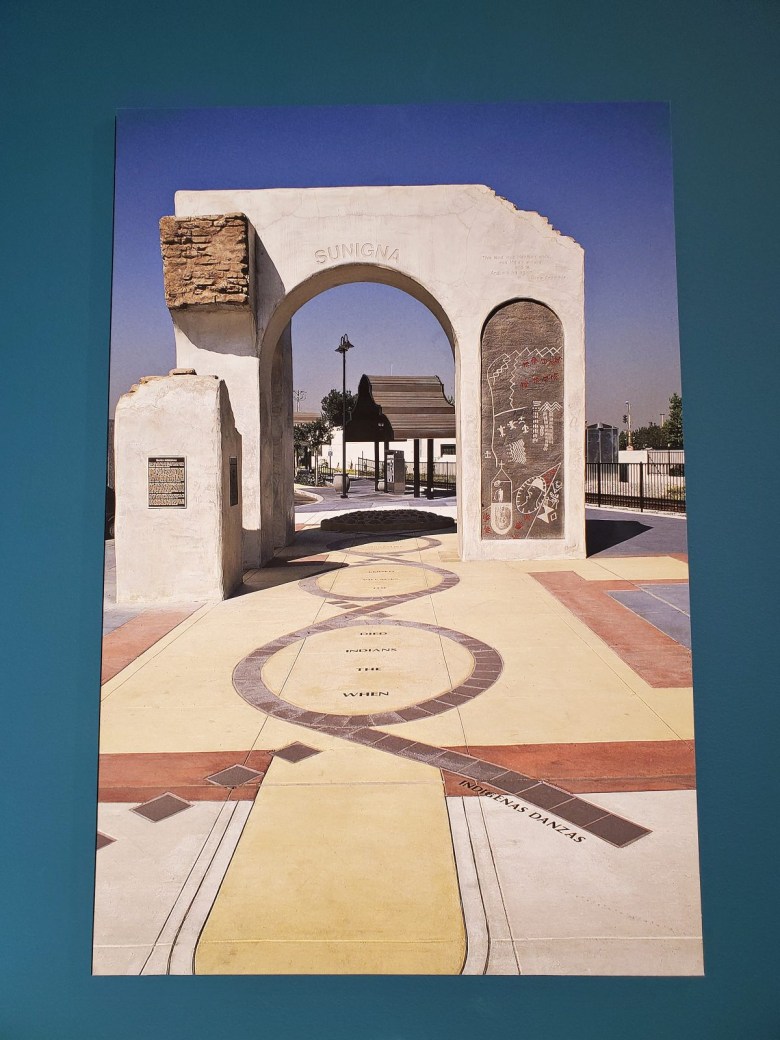

The high stakes of making art in the public realm are evinced in the controversy surrounding Baca’s monument, “Danzas Indígenas,” a plaza and platform commissioned for the Baldwin Park Metrolink commuter rail station in 1994. Drawing on the history and architecture of the nearby Mission San Gabriel, Baca’s design reflects the past and present of the Baldwin Park site. She combines indigenous, Spanish, and mestizo history with community-generated hopes for the city’s future, which are inscribed on the walls of the mission-style arch in the center of the plaza. Controversy arose a decade later when the anti-illegal immigrant group Save Our State (based not in Baldwin Park, but Ventura County), targeted the monument for attack for its perceived “anti-American” sentiment. Video footage of the protest and the recreation of the counter-protestors’ signs encouraging tolerance are powerful reminders that, as Moctezuma reiterated, “public space is contested space.”

The exhibition closes with “The Great Wall of Los Angeles,” which the curators were challenged with reimaging within the walls of the museum. Working with Baca and a team of MOLAA staff, Moctezuma and Urtiaga developed what they call an “immersive audiovisual experience” of the mural. Viewers enter a black box and are suddenly surrounded by a floor-to-ceiling projection of a desert landscape, which gives way to the Los Angeles River as it morphs into its current concretized state. The project is introduced with a short video detailing its production, significance, and contemporaneous reception before a scrolling presentation of the mural in its entirety. The overall effect is a dazzling, and at times dizzying, translation of the impact and immensity of the half-mile-long mural into the gallery format.

In her remarks at opening of Memorias de Nuestra Tierra, Baca described her experience of the retrospective as that of a river rock. She is incorporating river rocks in her upcoming expansion of “The Great Wall.” “I’m like that river rock,” she said. “Completely hewn by the buffeting of waters and the difficulty of times. You get rounded and you are solid … You are formulated by those experiences.” Baca has waited a long time for this moment. “I am grateful for the fact that this is happening while I’m alive,” she said. “And I’m grateful for having the experience of seeing it together in one place and having a new understanding … I think it will help me with the next work I do.”

Judy Baca: Memorias de Nuestra Tierra, a Retrospective continues at MOLAA (628 Alamitos Avenue, Long Beach) through January 31, 2022. The exhibition is curated by Gabriela Urtiaga and Alessandra Moctezuma.