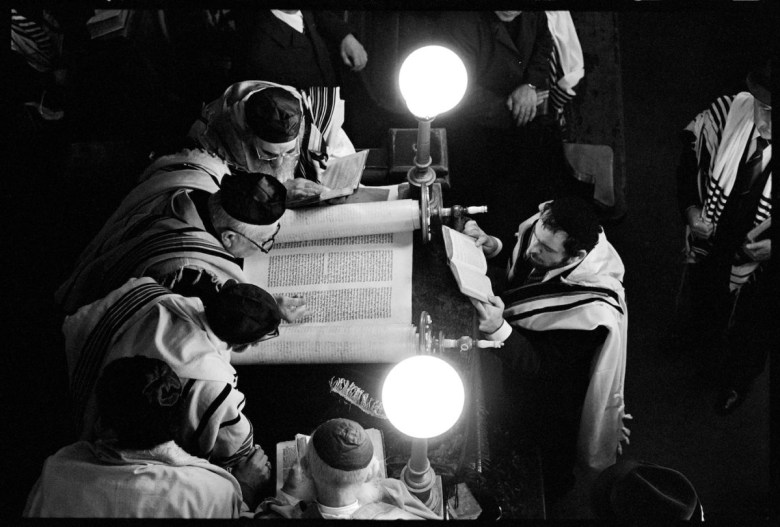

LOS ANGELES — In 1981, photographer Bill Aron flew to the Soviet Union to document the lives of Jews living under state-sanctioned repression and antisemitism. Shortly after arriving in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), he went to a synagogue and pulled out his camera, raising a commotion from the congregants. He froze, realizing it was Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar. Sticking to his mission, he continued photographing, and after the service, a woman explained that upon first seeing his camera, people suspected he might be a KGB officer. Once they realized he was American, there was relief that he would be taking their images back to the US to share their stories.

Thirty-six of Aron’s photographs from the trip are featured in Soviet Jewish Life: Bill Aron and Yevgeniy Fiks at the Wende Museum, which is dedicated to preserving Cold War artifacts and culture from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. The exhibition pairs Aron’s photographs with artwork by the Moscow-born, New York-based Yevgeniy Fiks, including a series that explores Birobidzhan, a semi-autonomous Jewish region near the Chinese border established by the Soviet regime in the 1930s as a Jewish homeland, a utopian but ultimately failed experiment. Taken together, the two bodies of work highlight the complicated, often contradictory experiences of Soviet Jews throughout the 20th century.

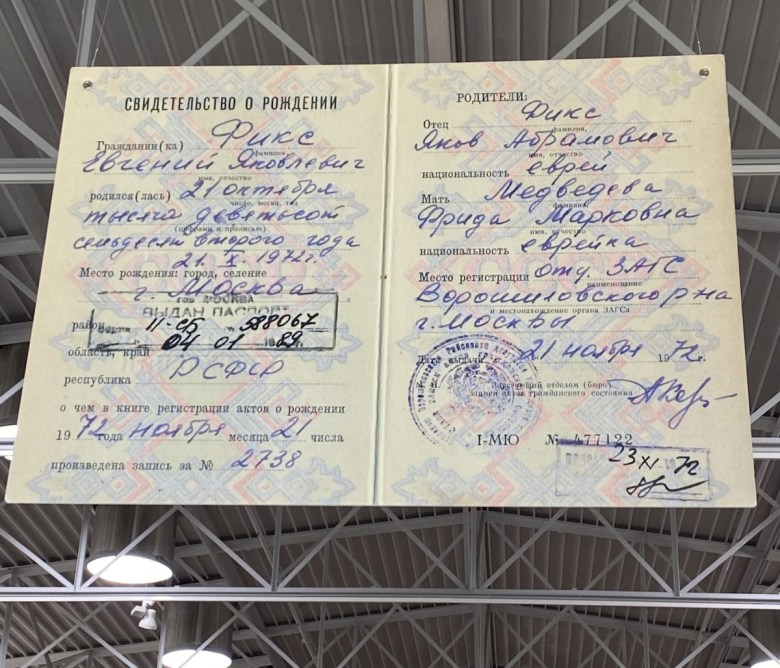

After the Russian Revolution, there was hope that some of the antisemitism deeply entrenched in Russian society would be overtaken by a pan-Soviet utopianism. In the early days, Jewish cultural activities such as Yiddish theater and literature were officially sponsored and promoted, provided they did not run afoul of party doctrines. (This was in contrast to the regime’s disdainful view of religion, including Judaism, in general.) However, official attitudes towards Jews soon began to turn increasingly repressive. In the 1930s, an internal passport system was introduced that listed the nationality of every Soviet citizen, identifying Jews as an ethnic group similar to Armenians, Ukrainians, or Russians. Stalin’s regime was especially hostile, culminating in an anti-cosmopolitan campaign of 1948-49 which targeted “cosmopolitan elites,” most of whom were Jewish.

In the ensuing decades, a resistance movement grew among Soviet Jews who had become disconnected from their culture, language, and religion, but who were still being persecuted for their identity.

“We were not religious, we were completely atheistic. So what made you Jewish? It was your ID,” Mikhail Chlenov, a professor of the Philology Department and Linguistics at the Maimonides Academy Institute of the Kosygin Russian State University, and a leading organizer of Soviet Jews in Moscow, told me during a press event last November. “Officially, wherever you go, wherever you live, you were labeled as a Jew. Soviet for sure, but not Russian. If you are a Jew, you are not Russian.”

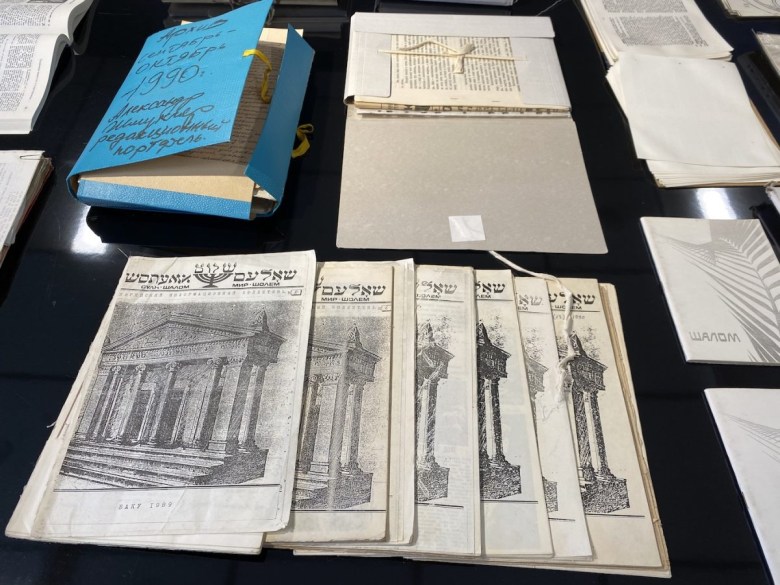

Many Jews applied to emigrate, mostly to the US or Israel, but the majority of requests were denied. Officially, a common reason was that they possessed “state secrets”; in reality, it was a combination of the belief that Jews harbored traitorous intent, the fear of “brain drain,” along with the implication that the Soviet utopia was anything but. These refuseniks, as they came to be known, suffered increased persecution, surveillance, and interrogations, lost their jobs, and in turn faced criminal charges of “social parasitism” for being unemployed. Together with culturniks — those who did not apply for an exit visa, but who were still involved in the movement, like Chlenov — the refuseniks sought to rekindle their Jewish identity by learning Hebrew and Jewish culture, establishing a clandestine distribution network of banned material and publications — known as samizdat (literally “self-publishing”) — throughout the Soviet Union.

In addition to being the Wende’s first exhibition with a specifically Jewish focus, Soviet Jewish Life is the first endeavor of the Robin Center for Russian-Speaking Jewry. Underwritten by Wende Museum Board and Committee members Edward Robin and Peggy Robin, the newly founded center aims to preserve the history of the Soviet Jewish experience and make it accessible to the public. This includes public programming, exhibitions, and archiving and digitizing collections of samizdat which fall into three categories: underground periodicals, correspondence between refuseniks, and official documents.

“What you really see from this is how nuanced and complicated these things are. Some people wanted to be totally hidden. Some people want to make a stand. Some people are in prison. Some people kind of toe the line,” the Wende’s founder and executive director, Justinian Jampol, told me. “There’s no one story here, but I think that’s what makes it interesting.”

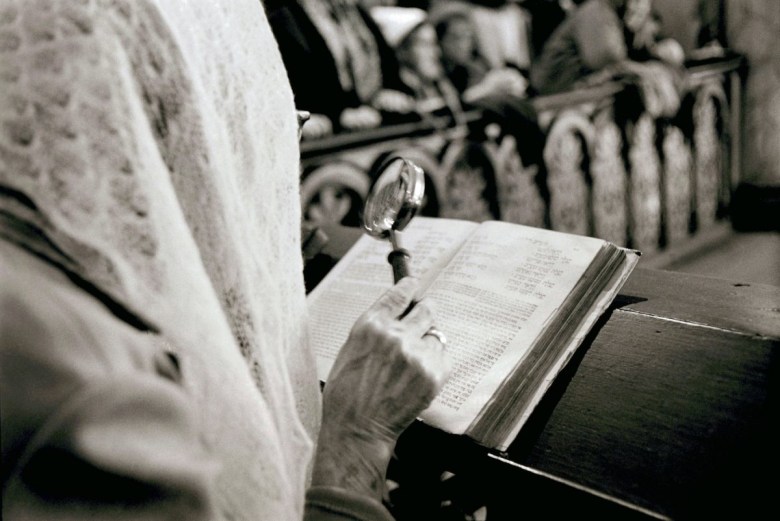

This complex situation is captured in Aron’s photos, depicting both religious Jews in synagogue, as well as portraits of refuseniks and their families. It was mostly older Jews, those who still had some connection to their religion and who were more likely to be retired and therefore had less to lose, who attended synagogue. (When I asked Chlenov if he attended synagogue on shabbat, he laughed and said, “I didn’t know what that meant!”)

Most of the collected samizdat covers two decades, roughly from the Six-Day War in 1967, which led to the severing of diplomatic ties between the USSR and Israel and increased persecution of Soviet Jews, to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. This period was characterized by fluctuations of tightening and loosening of restrictions, stretches when Jews were allowed to leave followed by crackdowns. Between 1970 and 1988, 300,000 Jews left the Soviet Union, while in the ensuing 30 years, about 1.7 million have emigrated. Almost 25,000 of those settled in Los Angeles.

“Our genuine sense was that any minute now, the door would close. We weren’t sure we would get out until we landed in Austria,” said Marina Yudborovsky, CEO of Genesis Philanthropy Group, a funder of the Robin Center, who fled the Soviet Union in 1989 before settling in New York. “My aunt had left in the ’70s and then that door closed, and we had no contact for years. Her brother had to disown her. Otherwise, he would have been fired.”

Parallel to the struggle of Jews inside the Soviet Union, there was an international movement to raise awareness to their plight and support them beginning in the early 1960s. (My parents actually met at a demonstration during a performance of the Moscow Circus on Ice at Madison Square Garden in 1972.) This link is captured in Fiks’s “Withered and Restricted, According to Lamed Kof,” in which a blown-up copy of his birth certificate, identifying his parents as Jews, hangs over the gallery entrance, while a recording of a 1966 speech by Martin Luther King Jr. in support of the cause of Soviet Jewry plays over speakers. While this movement is fairly well documented, the refusenik movement itself is less well chronicled. “There was almost no collection that we knew of, other than rumors about where these things were, for those who were actually the subjects themselves of the movement,” said Jampol.

Much of the samizdat at the center comes from the collection of Sasha Smukler, a refusenik leader who emigrated to the US in 1991 and went to great lengths to create and distribute samizdat. “Behind it was the involvement of hundreds of people who had no clue about each other,” he explained. Books smuggled in by visitors would need to be translated into Russian. Then, each page would be photographed on microfilm, which would be taken by couriers on trains to labs in different parts of the Soviet Union to be developed. Couriers would hide the microfilm, “right there in your mouth or you can put there,” Sasha joked pointing to his backside. “It’s like distributing drugs.”

The copy machines to print the books were smuggled in piece by piece to avoid detection. One of the largest printing operations was in the ghetto of the Bukharan Jews, “because the KGB never came inside the ghetto,” and books were sent out hidden in shipments of fruit.

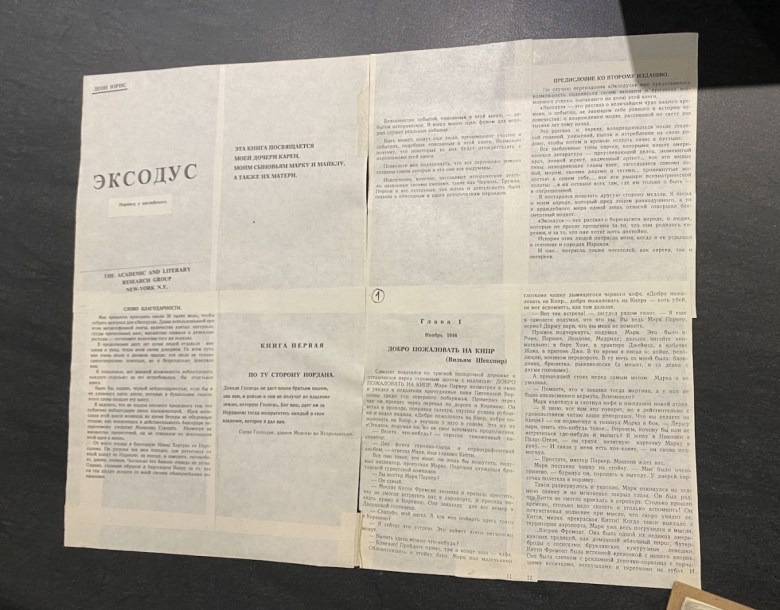

At the museum, Smukler stood before a self-published copy of Leon Uris’s 1958 historical novel about the founding of Israel, Exodus. A wildly popular book when it was published, Exodus has since been criticized for its negative depiction of Arabs and for a one-sided portrayal of the origins of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. According to Smukler, it was an essential book for the refuseniks “in order to build up your identity” — an anecdote that highlights Soviet Jewry’s connection to Zionism. Israel is home to the largest number of former Soviet Jews, and actively courted them when Jewish immigration from Western Europe and the US was less robust than the young nation had hoped. “Most of us were so scared and so assimilated, so suppressed in our classrooms. And we hid it. The fear was always inside us. That book let that fear go away,” said Smukler.

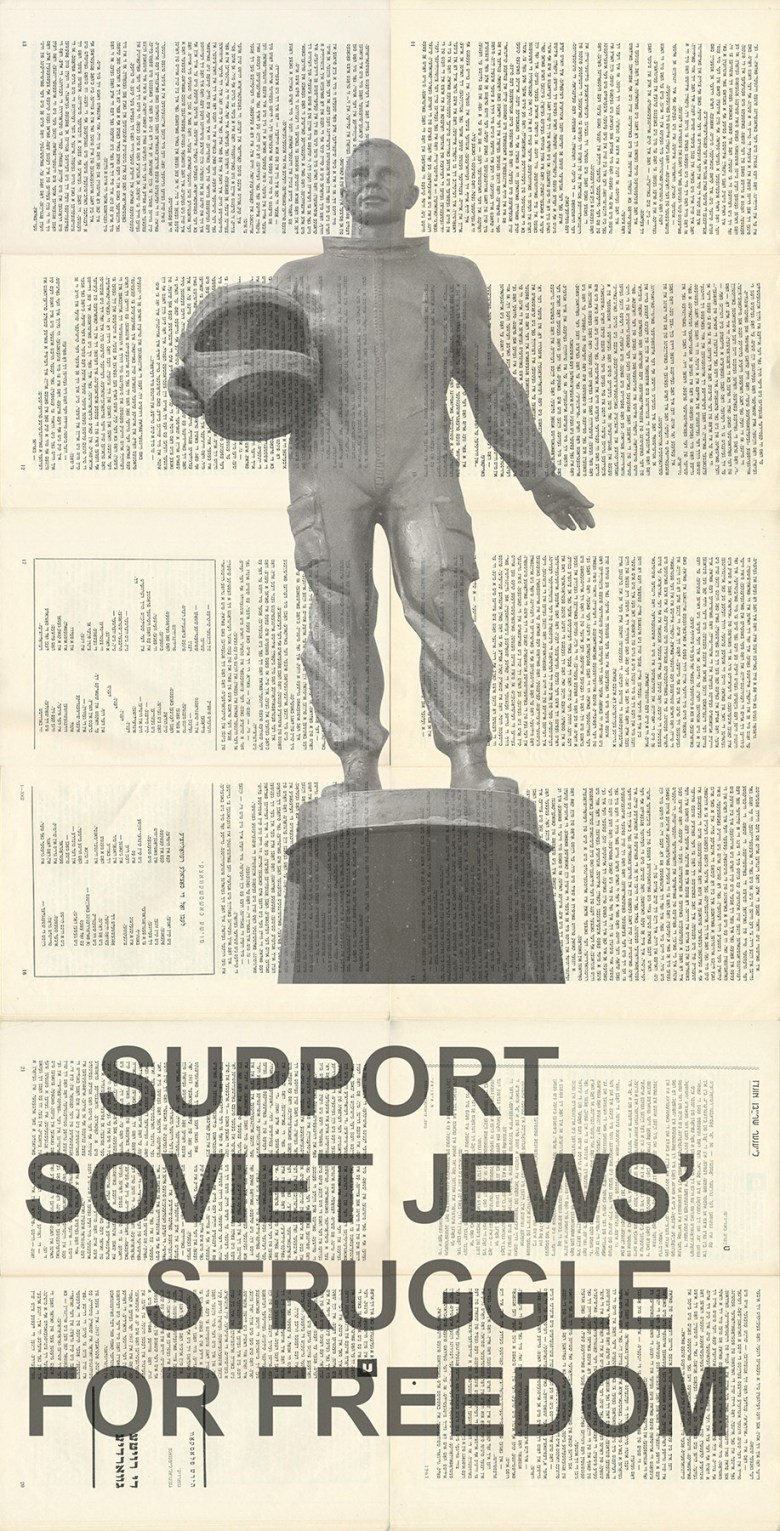

In contrast to a Jewish identity based in large part on Zionism, Fiks’s work imagines the possibility of Jewish freedom within the Soviet Union. His “Yiddish Cosmos” project is a futurist fantasy that imagines the intersection of the Soviet Space Program and the Soviet Jewish experience. Although many Soviet Jews were well-educated engineers and scientists, they still faced state-sponsored discrimination. This extended to the Soviet space program, which did not send cosmonaut Boris Volynov into space until 1969 because of his Jewish background, eight years after his colleague Yuri Gagarin became the fist human to voyage into space. “Yiddish Cosmos” locates Soviet Jewish liberation in a kind of scientific egalitarianism, where freedom is possible not only abroad, but at home as well.

The stories chronicled in the Robin Center’s archives and Aron’s and Fiks’s work are specific to a certain time and place, but they are nonetheless tied to contemporary issues of immigration, refugees, and resistance. The experience of the refuseniks, who tried to leave their homeland even when that almost certainly meant increased persecution, speaks to the scores of refugees and migrants who leave their families and risk their lives to travel to a country they may have never seen before.

“And when we said goodbye, it was very clear to all of us that we would never see each other, that we would never be able to come back,” recalled Yudborovsky. “We were leaving everything. We were seeing these places for the last time. We’re seeing these people for the last time …. Many of [the refuseniks] did it because they thought there was no future otherwise. Maybe they wouldn’t have gotten fired from their job at that moment. But you were still at the mercy of the state.”

“This is an example of a truly successful campaign for human rights, equality, and freedom,” she said. “What kept these people alive was that their names and faces were known abroad. In the end, it opened that door and allowed them to leave.”

Soviet Jewish Life: Bill Aron and Yevgeniy Fiks continues at the Wende Museum (10808 Culver Boulevard, Culver City) through March 20.