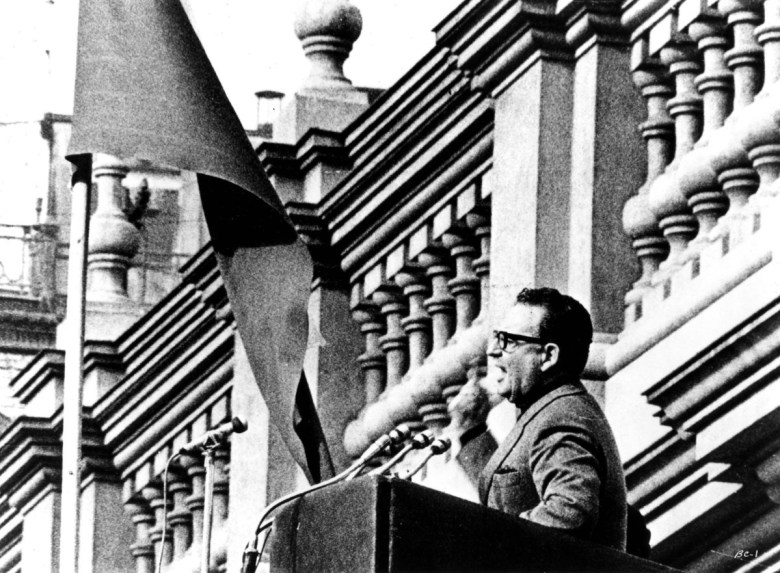

On September 11, 1973, a military coup in Chile overthrew President Salvador Allende. Previously renowned as South America’s most stable democracy, the country became a crucible for neoliberalism under the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. During these years, tens of thousands of citizens were imprisoned, tortured, murdered, and/or disappeared.

Hundreds of thousands fled the terror, among them leftist filmmaker Patricio Guzmán. Just a few years prior, he had directed his first feature, a celebratory look at the myriad progressive policies and social programs that Allende’s administration had implemented in its early days, fittingly called The First Year. In 1973, amid right-wing agitation, a concerted opposition movement in government, and rising militaristic rumblings (all supported behind the scenes by the CIA), Guzmán and a small crew took to the streets to film protests, counter-protests, and eventually the military storming Santiago. After the coup, he settled in France, where he remains today, eventually turning the footage they captured into the three-part epic The Battle of Chile. Among the most important documentaries and political films ever made, its portrait of revolutionary fervor and the ferocity of counterrevolution remains bracingly intense 50 years later — the first part ends with one of the film’s cameramen recording the moment of his own death at the hands of the military.

Guzmán has continued to make documentaries on his homeland in the decades since, first from exile and then in Chile, after being able to return. Much of his work deals with the coup, the dictatorship, and their respective aftermaths: The lost promise of Allende’s presidency, enduring personal and collective trauma, the continued possibility for new revolution. To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the coup and celebrate the recent restorations of The First Year and The Battle of Chile, Icarus Films and Cinema Tropical have partnered with Anthology Film Archives, IFC Center, and the Brooklyn Academy of Music to screen a retrospective of Guzmán’s films in New York. The series also includes his trilogy of films relating parts of Chile’s geography to the lingering effects of the dictatorship, as well as his most recent feature, My Imaginary Country, about contemporary protests in the country.

Ahead of the series, Hyperallergic sat down with Guzmán over Zoom and, with the help of a translator, discussed the dangers of filming during the coup and all that happened after. This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Hyperallergic: What led you to start work on The First Year right out of film school?

Patricio Guzmán: I wanted to film that spectacular moment in Chile. The campaign of Salvador Allende caused a huge mobilization in all parts of society. He was the first socialist president elected democratically. Chile had become a revolutionary country. It was an era full of joy, of hope, of interesting projects. I felt I needed to document it.

H: Did you have a film in mind when you started shooting the events leading up to the coup, or did you simply want to document what was happening? It was clearly dangerous for you; Part I ends with the camera falling to the ground and the image going dark because the man holding it was shot and killed.

PG: We had a team of five people, and we were writing the script as we were going along. We wanted to just show this moment. Allende was at the height of his charisma and mobilization, and witnessing it made us so passionate. This was an era when politics were a total spectacle of manifestos, political parties, mass participation.

Leonardo Henrichsen, a cameraman from Argentina, is the one you speak of who we see dying in Battle of Chile. Two months before the coup, he was shot in the breast by a military officer. Another crew member, Jorge Müller, disappeared the year after the coup. He had an amazing talent for the camera, and he shot footage until the film ran out. He was assassinated with his girlfriend, an actress.

We passed through many hard times. We were imprisoned in a camp with others for several days; it was full of trucks and buses. Luckily, the officers were told to retreat, and we were able to escape. Mainly, we had many encounters with the right. At that time, the right in Chile had a militia group called Fatherland and Liberty, and they were dangerous people. Filming was full of obstacles because the right always tried to stop it.

H: You were one of the tens of thousands of people imprisoned in the National Stadium in the aftermath of the coup, and you left the country not long after you were released. How did you decide to settle in France afterward?

PG: I left the National Stadium after 15 days. They let me go because they figured I wasn’t dangerous, and they essentially picked me out along with the rest of my crew. I got into contact with students in Madrid because I studied there and had friends there. I left for Madrid with our cameraman, the producer of the film, and our sound guy.

Then I went to Paris because one of the people who was important in the history of this movie is Chris Marker. He visited Chile in 1971 and had seen The First Year, and he encouraged me. Chris shipped us a huge amount of film through the airport when we were making Battle of Chile. When I was in exile, he contacted me and helped us complete the film, and I eventually went to Havana to edit it.

H: You had to smuggle the footage you’d shot out of Chile. How was this accomplished?

PG: We went to the Cuban embassy in Santiago, and the ambassador told us to send the stock to Sweden, and it would then be sent to Havana. He was incredible. We left it with him, and it was in transit or holding for a long time, and then finally they called us. Miraculously, nothing was missing, and we edited the footage there in Cuba. That was when we realized we had so much valuable material, and the only possible way to include it all was to divide the film into multiple parts.

H: When did you first feel safe enough to go back to Chile?

PG: I first returned two years before Pinochet fell. It was a completely different country, one that I didn’t recognize. A country full of military Jeeps and machine guns, silent, hurt, and wounded, a ghost country. A country that had been smashed. It was a tragedy. I was in complete anguish. I went to the Vicariate of Solidarity, which was organized by the Catholic Church. Its mission was to help people who had been persecuted and then left during the coup. That’s where I got the idea for the next film I made.

H: You’ve tracked Chile’s history and developments for over 50 years now. Do you see much difference in how young people with no lived memory of the dictatorship think of it, versus people who lived through it?

PG: There is a movement of university students who are creating wonderful things in Chile right now. They have a certain confidence in the future. And there is a left-leaning government. But it is still a country that has been severely hit, and there are still a lot of social tensions, with many social programs that don’t function. It’s because of the class of people who own industry, they’re all on the right, and that still creates a problem.

Patricio Guzmán, Dreaming of Utopia: 50 Years of Revolutionary Hope and Memory screens at various venues in New York from September 8 to 15.